China's Nationalist Heritage

Mini Teaser: Chinese leaders have reverted to a pre-Communist ideology of national rejuvenation. This could complicate foreign affairs.

As the Japanese had reacted to Commodore Matthew Perry’s forcible opening of trade rights in 1854 by seeking to learn from the West, so now Chinese reformers, including Sun Yat-sen, went to Japan to investigate the sources of its new strength. The Japanese at this time were not envious of the West; they despised it. Despite having lost battles to Western militaries, they felt superior. This was reflected in their reference to Westerners, for instance, as the “feet of humanity.” This was the Japan that became the source of China’s learning about the West and modernity. From 1867 to 1870, the Japanese scholar Fukuzawa Yukichi wrote a ten-volume book called Things Western. He literally had to create new words to describe Western institutions and concepts, including the idea of “freedom,” which was translated into something approximating “selfishness.” While Japanese intellectuals read widely, including the work of social-contract theorists such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and liberals such as John Stuart Mill, Prussian martial thinking and works of social Darwinism gained the greatest traction in Japan. That’s because they resonated with indigenous ideas about a natural social order and hierarchy. Edward Morse, an American zoologist at Tokyo University, introduced Darwin to appreciative Japanese audiences in the 1870s. In the last quarter of the century, several translations of Darwin’s Descent of Man enjoyed wide circulation in Japan, and even more popular were works by Herbert Spencer, who coined the term “survival of the fittest” after reading Darwin’s On the Origin of Species.

Sun and other architects of Chinese nationalism were deeply impressed by how Japanese modernizers in this period committed themselves to increasing Japan’s national power and raising the quality of the Japanese population, consistent with the lessons of Spencer’s social Darwinism. The Japanese developed a formula for embracing modern technology without adopting foreign (i.e., liberal) political, social or cultural arrangements. The catch phrase for this was “Eastern values, Western learning.” In Chinese, this became the ti-yong essence-function formula, and Sun Yat-sen’s contemporary and fellow exile in Japan, the prominent Chinese reformer Kang Youwei, wrote memorials warning the Qing emperor against indiscriminate Westernization that would result in “moral degeneration.” As good students of Western positivist philosophy, Chinese reformers also believed that China’s social situation could be diagnosed scientifically. Accordingly, they emphasized the need to prescribe only those particular Western institutions or practices that were suitable for China to adopt in light of its own guoqing or national condition. Within twenty years, Japan’s modernization drive had succeeded. Perhaps even more shocking to the Chinese than their own loss to Japan was Japan’s defeat of Russia in 1905. Now Chinese reformers had evidence that the West’s learning, if mixed properly with local strengths, could be used to defeat it.

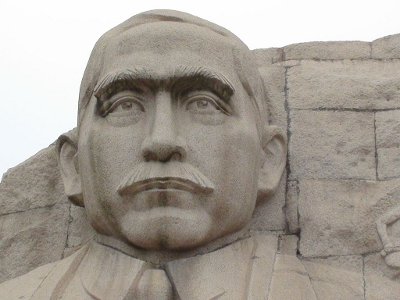

Even in cases where works were transmitted directly from the West to China, the Chinese scholar transmitters seemed to favor the same kinds of imports as their Japanese counterparts. The first Western book directly translated into Chinese was Yan Fu’s rhetorical rendering of Thomas Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics, which he was inspired to produce after the Chinese defeat in the first Sino-Japanese War. (The translation appeared in 1896, one year later, and Yan also translated the work of Herbert Spencer.) Thus did China import certain nineteenth-century European ideas of nation, race and social Darwinism. From the beginning, China’s understanding of nation-states was embedded in a zero-sum perspective on the international environment, a place where only the fit survive. The reformer Liang Qichao, who joined Sun Yat-sen and Kang Youwei in Japan for a time, imported the Japanese term for nationalism back to China as minzu zhuyi. The Chinese word for nationality, minzu, comes from the Japanese minzoku, which conjures the idea of bloodlines and racial purity. When Sun first developed his “Three Principles of the People” (i.e., nationalism, democracy and welfare) in Tokyo in 1905, he was consciously trying to emulate Abraham Lincoln’s idea of government “of the people, by the people, for the people,” and yet Sun saw fit to include a decidedly un-Lincolnian paean to the lineage of the Chinese race:

The greatest force is common blood. The Chinese belong to the yellow race because they come from the blood stock of the yellow race. The blood of ancestors is transmitted by heredity down through the race, making blood kinship a powerful force.

The “yellow race” chauvinism evident in this passage comes through in other important contributions from this formative era of Chinese nationalism. It was at this time that the modern Chinese discourse of guochi or national humiliation was born. While the emphasis on humiliation may seem negative, to Chinese ears the implication is that the Chinese, defined as descendants of the Yellow Emperor, are the heirs of a glorious civilization and will recover their preeminence. In Sun’s words, “We have become a sheet of loose sand and so have been invaded by foreign imperialism and oppressed by the economic control and trade wars of the [imperialist] Powers, without being able to resist.” The task for China was to “become pressed together into an unyielding body like the firm rock which is formed by the addition of cement to sand.” Sun argued that this would require reducing the freedom of the Chinese people, cementing his own status as an authoritarian rather than a republican leader.

THE CCP patriarch Mao Zedong, who defeated Sun Yat-sen’s Kuomintang successors in China’s civil war and who is now credited with launching China on the road to recovery from humiliation, adapted only some of the key concepts of the late Qing and republican Chinese reformers during his tenure from 1949 to 1976. But in the post-Mao era, the original Chinese nationalism has come back to the fore. It is so dominant in today’s CCP discourse that the party has to finesse the tensions between Marxism and nationalism by means of word tricks, such as saying that China has progressed from the stage of revolution to the stage of development. For Mao, his revolution trumped restoration as the national priority, though he did appropriate Sun’s language about China as a heap of “loose sand” requiring unification, and he justified using the ti-yong formula and the idea of guoqing or national conditionon the grounds that Marxism requires the study of local conditions. Overall, though, Mao propounded a unique synthesis of Western Marxism and Chinese ti for his own purposes under the heading of Marxist-Leninist Mao Zedong Thought. When Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping led China into a new age of “reform and opening,” however, he explicitly encouraged a reconsideration of turn-of-the-century ideas to justify increased commerce and engagement with the rest of the world. To deal with the sharp transition from Mao’s revolution to Deng’s restoration, subsequent CCP general secretaries have formulated a narrative celebrating two great moments along China’s journey from humiliation to rejuvenation. First is Mao’s 1949 victory, which led to the expulsion of foreign forces and the unification of all of China under a single leader. Second is Deng’s ascension in 1978, when the path to development was illuminated, making possible the relative prosperity that China now enjoys.

The conservative Chinese analyst Yan Xuetong argues that rejuvenation today conjures “the psychological power” associated with China’s rise “to its former world status.” The concept assumes both that China is recovering its natural position and that this means being the “number one nation in the world.” The echoes of early Chinese nationalists such as Sun are clear. Given the character of Chinese nationalism, the outlook for Chinese policy and behavior in the future might be problematic. Considering Chinese nationalism in its full context raises several causes for concern.

The sociologist Liah Greenfeld has produced a typology of nationalism along two dimensions based on historical analysis of the English, French, German and Russian cases. The first dimension is the individualist-collectivist dichotomy. Greenfeld diagnoses French, German and Russian nationalisms as collectivist, while those of England and the United States are viewed as individualist. Already in Tudor England the individual, as opposed to the collective, was emerging as the basic political unit; elsewhere in Europe, it was still only a monarch or a select few who were thought to represent the best interests of the general population. Greenfeld’s second dimension involves the criteria of membership in the state—namely, whether it is civically or ethnically based. German and Russian nationalisms are based on ethnic membership, as opposed to both the individualist British and the collectivist French varieties, in which membership is civic, based on the opting in of citizens. Greenfeld’s typology and study of history yield two conclusions relevant to China. First, nationalisms that are both collectivist and ethnic are by their nature suspicious of and hostile to individualist, civic or liberal nationalisms. Several twentieth-century wars, including the two world wars, attest to this. Second, ethnic nationalisms are difficult to sustain in multiethnic countries, and countries featuring collectivist, ethnic nationalisms tend to be subject to violent revolutions rather than peaceful political evolution.

From imperial Confucianism to Maoism and the residual Leninist attributes of party rule in China today, the dominant political currents in China have all prioritized the collective over the individual, as seen through the prism of Greenfeld’s analysis. The Chinese party state falls firmly in the collectivist camp. The CCP purports to represent and speak for the Chinese people as a whole, and society as a whole is invoked in contemporary slogans such as xiaokang shehui (comfortable society), hexie shehui (harmonious society), shehui jianshe (social construction) and shehui guanli (social management). The Chinese people are usually described as laobaixing or commoners (literally, the “old hundred surnames”). The word qunzhong, or “the masses,” is the Leninist equivalent of the laobaixing, and used most often, along with the collective renmin, meaning “the people,” in political speech. One often hears Chinese people speaking in English use the term “masses” or even “peasants” to describe the majority of China’s population. In a 2009 article for a Western academic journal, even the self-described liberal Chinese professor Cong Riyun defines his terms in ways that make clear that he considers an elite few to represent the interests of the majority of Chinese citizens—instead of considering each citizen to be a bearer of political rights in his or her own right: “In China, the absolute majority of the population is mass in root. They, peasants in particular, have almost no consciousness of or identification with the state. This consciousness and identification lodge in intellectual and political elites.” Despite identifying himself as a liberal, Cong does not sound so different from rank-and-file party officials in the way he talks about the Chinese citizenry. The party secretary of a city in Guangdong Province recently complained, “Ordinary people have bigger and bigger appetites, and become smarter every day. They are harder and harder to control.” Though difficulties perhaps mount, China’s single party still considers itself the proper steward of the collective known as “ordinary people.”

Image: Pullquote: The reality is more nuanced than either the image of European-style fascism or the theory of Chinese democratization, though it is unfortunately closer to the former than the latter. Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: The reality is more nuanced than either the image of European-style fascism or the theory of Chinese democratization, though it is unfortunately closer to the former than the latter. Essay Types: Essay