The Good Autocrat

Mini Teaser: A stark contrast exists between the tyrannical rulers of the Middle East and the benign despots of East Asia. The precepts of Enlightenment thought dictate freedom for all, but Confucian leaders offer a heretical alternative to Western ideals.

Both of these countries, which lie at the two geographical extremities of the Arab world, have not been immune to demonstrations. But the protesters in both cases have explicitly called for reform and democracy within the royal system and have supported the leaders themselves. King Mohammed and Sultan Qaboos have moved vigorously to get out in front of popular demands by reforming their systems instead of merely firing their cabinets. Indeed, over the years, they have championed women’s rights, the environment, the large-scale building of schools and other progressive causes. Qaboos, in particular, is sort of a Renaissance man who plays the lute and loves Western classical music, and who—at least until the celebrations in 2010 marking forty years of his rule—eschewed a personality cult. The characteristics, then, of the benign dictator are evident, at times hewing to propositions set forth by the likes of Berlin: freedom may come as much from stability as from democracy; leaders must adhere to the will of the people, they need not in all cases be chosen by them. Yet in the Middle East these dictators remain the exception to the rule, and this is why quasi monarchies of the iron-fisted Assad or the crazed and tyrannical Qaddafi are now under assault.

THE PLACE where benevolent autocracy has struck deep and has systematic roots is Asia. Any discussion of whether and how democracy can be successfully implemented might, because of the current headlines, begin with the Arab world, but the answers such as there are will, nevertheless, ultimately come in from the East. It is in those Asian lands that conventional Western philosophical precepts are challenged.

The ideology by which Asian autocrats stand in opposition to the likes of Mill and Berlin falls—to some extent—under the rubric of Confucianism. Confucianism is more a sensibility than a political doctrine. It stresses traditional authority, particularly that of the family, as the sine qua non of political tranquility. The well-being of the community takes precedence over that of the individual. Morality is inseparable from one’s social obligation to the kin group and the powers that be. The Western—and particularly the American—tendency is to be suspicious of power and central authority; whereas the Asian tendency is to worry about disorder. Thus, it is in Asia, much more so than in the Middle East, where autocracy can give the Western notion of freedom a good run for its money. The fact that even a chaotic democracy is better than the rule of a Mubarak or a Ben Ali proves nothing. But is a chaotic democracy better than the rule of autocrats who have overseen GDP growth rates of 10 percent annually over the past three decades? It is in places like China, Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam where good dictators have produced economic miracles. These in turn have led to the creation of wide-ranging personal freedoms, even as these leaders have compelled people against their will on a grand scale. Here the debate gets interesting.

Indeed, probably one of the most morally vexing realizations in the field of international politics is that Deng Xiaoping, by dramatically raising the living standard of hundreds of millions of Chinese in such a comparatively short space of time—which, likewise, led to an unforeseen explosion in personal freedoms across China—was, despite the atrocity of Tiananmen Square that he helped perpetrate, one of the great men of the twentieth century. Deng’s successors, though repressive of political rights, have adhered to his grand strategy of seeking natural resources anywhere in the world, wherever they can find them, caring not with which despots they do business, in order to continue to raise the economic status of their own people. These Chinese autocrats govern in a collegial fashion, number many an engineer and technocrat among them, and observe strict retirement ages: this is all a far cry from the king of Saudi Arabia and the deposed leader of Egypt, sleepy octogenarians both, whose skills for creating modern middle-class societies are for the most part nonexistent.

Park Chung Hee, in the 1960s and 1970s, literally built, institutionalized and industrialized the South Korean state. It was Park Chung Hee’s benign authoritarianism, as much as the democracy that eventually followed him, that accounts for the political-economic powerhouse that is today’s South Korea.

Then, of course, there is the founder of current-day Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew. In 1959, Lee became prime minister of what was then a British colony. He retired from that post over thirty years later (though he continued to exert significant power until very recently). As the British prepared to withdraw in the 1960s, Lee attached Singapore to Malaya, helping to form Malaysia as a bulwark against Indonesian expansionism. When racial tensions between ethnic Malays in the Malay Peninsula and ethnic Chinese in Singapore made the new federation unworkable, Lee seceded and the independent city-state of Singapore was born. When Lee assumed power, Singapore was literally a third-world malarial hellhole beset by ethnic tensions and communist tendencies; it was barely a country in any psychological sense and it certainly could not defend itself against powerful neighbors. Lee turned it into a first-world technological dynamo and transportation hub, with one of the highest living standards worldwide, and with a military that is among the best anywhere pound for pound. Along the way, a strong national consciousness was forged in the vein of a twenty-first-century trading state. Lee’s method of government was not altogether democratic, and his intrusion into people’s lives bordered on the petty and anal-retentive: banning spitting, the use of tobacco and chewing gum. The press, of course, was tightly controlled. Whenever criticized, Lee scoffed at how an uninhibited media in India, the Philippines and Thailand had not spared those countries from rampant corruption; multinationals love Singapore in large measure because of its meritocracy and honest government. Yes, Singapore is green with many parks, and so immaculate it borders on the antiseptic. But it is also a controlled society that challenges ideals of the Western philosophers.

For Lee has provided for the well-being of his citizens without really relying on democracy. His example holds out the possibility, heretical to an enlightened Western mind, that democracy may not be the last word in human political development. What he has engineered in Singapore is a hybrid regime: capitalistic it is, but it all occurred—particularly in the early decades—in a quasi-authoritarian setting. Elections are held, but the results are never in doubt. There may be consultations with various political groupings, yet, in fifty years, there is still little sign that the population is fundamentally unhappy with the ruling People’s Action Party (though its majority has fallen somewhat). Unsurprisingly, Lee makes liberals supremely uncomfortable. Fundamentally Mill, Berlin and many other Western philosophical theorists and political scientists—from Thomas Paine and John Locke to Francis Fukuyama of late—hold that people will eventually wish to wrest themselves from the shackles of repressive rule. That the innate human desire for free will inevitably engenders discontent with the ruling class from below—something we have seen in abundance in the lands of the Arab Spring. Yet, Confucian-based societies see not oppression in reasonably exercised authority but respect; they see lack of political power not as subjugation but as order. Of course, this is provided we are talking about a Deng or a Lee and not a Pol Pot.

To be sure, Asian autocracies are not summarily successful. Elsewhere, political Confucianism is messier. In Malaysia, Mahathir bin Mohamad lifted his people out of abject poverty and easygoing cronyism to mold another high-tech, first-world miracle; but he lacks virtue because of the tactics he employed as methods of control: vicious campaigns against human-rights activists and intimidation of political opponents, which included character assassination. The Vietnamese Communist leadership has lately overseen dynamic economic growth, with, again, the acceleration of personal freedoms, even as corruption and inequalities remain rampant. Think for a moment of Vietnam, a society that has gone from rationing books to enjoying one of the largest rice surpluses in the world in a quarter of a century. It recently graduated in statistical terms to a middle-income country with a per capita GDP of $1,100. Instead of a single personality with his picture on billboards to hate, as has been the case in Egypt, Syria and other Arab countries, there is a faceless triumvirate of leaders—the party chairman, the state president and the prime minister—that has delivered an average of 9 percent growth in GDP annually over the past decade. Nevertheless, Vietnam’s rulers remain fearful of public displays of dissatisfaction spread across the Internet. And there is China: continental in size, it produces vastly different local conditions with which a central authority must grapple. Such grappling puts pressure on a regime to grant more rights to its far-flung subjects; or, that being resisted, to become by degrees more authoritarian. So terrified is its regime of its own version of an Arab Spring that it has gone to absurd lengths to block social media and politically provocative areas of the Web.

HERE IS the dilemma. Yes, a social contract of sorts exists between these citizens and their regimes: in return for impressive economic-growth rates the people agree to forego their desire to replace their leaders. (Truly, East Asian autocracies have not robbed people of their dignity the way Middle Eastern ones have.) But even as such growth rates continue unabated—to say nothing of if they collapse or even slow down—at higher income levels, this social contract may peter out. For as people become middle class, they gain access to global culture and trends, which prompts a desire for political freedoms to go along with their personal ones. This is why authoritarian capitalism may be just a phase, rather than a viable alternative to Western democracy.

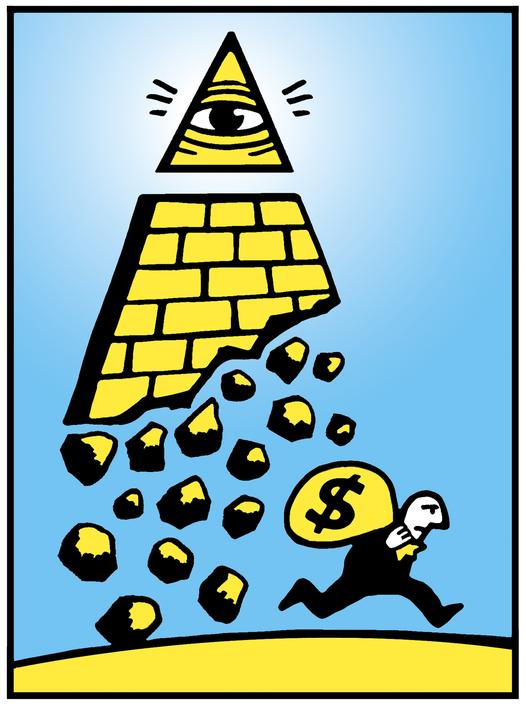

Image: Pullquote: As Isaiah Berlin intimates, what follows dictatorial rule will not inevitably further the cause of individual liberty and well-being.

Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: As Isaiah Berlin intimates, what follows dictatorial rule will not inevitably further the cause of individual liberty and well-being.

Essay Types: Essay