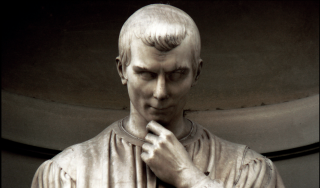

500 Years and Counting: Why the World Is Still Terrified by Machiavelli

The one and only. The original Sith Lord.

To be sure, Machiavelli was well aware of what later realists would call the security dilemma. As political and military advisor to Soderini, he had sought to manipulate the shifting power balance amongst Italy’s wary and jealous city-states. He had seen his beloved Florence, after a litany of errors (including reliance on too-powerful allies like France), capitulate to its enemies. Such experiences taught him that “it is impossible for a state to remain for ever in the peaceful enjoyment of its liberties and its narrow confines; for though it may not molest other states, it will be molested by them and, when thus molested, there will arise in it the desire, and the need, for conquest.”

But Machiavelli differs from later realists like Hobbes—and more contemporary “neorealists” like the late Kenneth Waltz—in recognizing that human agency matters as much as the structural fact of international anarchy in determining both foreign policy behavior and ultimate outcomes in world politics. Through historical examples of successes and failures, Machiavelli reminds us that individuals matter. Yes, the world is perpetually changing, buffeting the state in all directions. But even if “there’s a Providence that shapes our ends”—as Shakespeare’s Hamlet observes—a leader’s choices can have a pivotal impact on politics, both domestic and international.

Machiavelli explores the interplay between material forces and human agency through the concepts of fortuna and virtu. All princes (and indeed, all people) are subject to societal and natural factors larger than themselves. Still, “free will cannot be denied,” Machiavelli insists. “Even if fortune is the arbiter of half our actions, she still allows us to control the other half, or thereabouts.” Though fortune be capricious and history contingent, the able leader may shape his fate and that of his state through the exercise of virtu. This is not to be mistaken for “virtue”, as defined by Christian moral teaching (implying integrity, charity, humility, and the like). Rather, it denotes the human qualities prized in classical antiquity, including knowledge, courage, cunning, pride, and strength.

Machiavelli describes the relationship between fortuna and virtu in the The Discourses:

“For where men have but little virtu, fortune makes a great display of its power; and, since fortune changes, republics and governments frequently change; and will go on changing till someone comes along, so imbued with the love of antiquity that he regulates things in such a fashion that fortune does not every time the sun turns around get a chance of showing what it can do.”

The prince’s challenge is to ride the wave of fortuna, using virtu to direct it in the interest of the state, as necessity (necessita) dictates.

Machiavelli’s contributions to the tradition of political realism are enduring. They include his admonition to take the world as it is, rather than it should be; his recognition that power and self-interest play a paramount role in political affairs; his insight that statecraft is an art, requiring political leaders to adapt both to enduring structures and changing times; and his insistence that the dictates of raison d’état may conflict with those of conventional morality. It is this last contention—that the public and private spheres possess their own distinct moralities—that remains so jarring today.

We live, after all, in an age of democratic sovereignty, in which “princes” are elected by citizens and, as government officials, are expected to conduct themselves with probity, transparency and accountability. The global normative context for statecraft has also changed profoundly, thanks in large measure to the expansion and international codification of individual human rights. Much of the state-sanctioned violence taken for granted in Machiavelli’s day—whether the conquest of empires, the taking of slaves, or the commission of atrocities—is both legally and morally impermissible today, thanks to the expansion of human-rights law, humanitarian law, the laws of war, and the proliferation of international norms, treaties, and institutions defining certain acts as beyond the pale, authorizing sanctions or intervention to put an end to them, and providing judicial mechanisms to hold perpetrators accountable. Atrocities and illegal acts still occur, as Darfur or Syria remind us. But standards of legality and legitimacy have evolved, making these the exception rather than the norm.

In other respects, though, The Prince holds up well as a guide to politics, domestic and foreign. His accounts of official corruption in Florence, of decadence in the late Roman empire, and of deception by Italian popes would raise few eyebrows in contemporary Washington, D.C. Nor would modern readers be surprised to learn that in political life, it is more frequently the sinners than the saints that rise to power and cling to their positions.

Stewart M. Patrick is a senior fellow and director of the International Institutions and Global Governance Program at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Editor's Note: This piece first appeared in 2014. We are reposting due to reader interest.

Image: Wikimedia.