America’s Unmanned Systems Will Soon Dominate the Skies

In the not-too-distant future, the face of American airpower will dramatically shift.

Chief among these efforts is the Air Force Research Lab’s Rapid Dragon program, which aims to allow cargo aircraft like the C-130 and C-17 to deploy dozens of long-range cruise and anti-ship missiles in a single volley. Rapid Dragon includes a modular palletized munition system that allows for stacks of six missiles per pallet in the C-130 and as many as nine per pallet in the larger C-17. These pallets were designed to accommodate the AGM-158 Joint Air to Surface Stand-off Missile (JASSM), but it stands to reason that they can deploy the longer-ranged JASMM-ER as well as the AGM-158C Long Range Anti-Ship Missile as well, as they share the exact same exterior dimensions.

The pallets are rolled out the back of the aircraft like any other airdrop. Once deployed, a parachute opens to stabilize the pallet as the onboard control system fires the missiles to begin their trek of more than 500 miles (and potentially greater than 1,000) to their targets where they will deliver 1,100-pound explosive warheads to land or sea targets.

Last December, U.S. Air Force A-10 Thunderbolt IIs, often seen as a relic of a bygone era, began training to support this new approach to overwhelming enemy air defenses through chaotic volume by incorporating ADM-160 Miniature Air Launched Decoys (MALDs) into their arsenals. The A-10 can be fitted with as many as 16 of these handy decoys, which puts it on par with the much larger B-52 Stratofortress.

The nine-foot-long, 300-pound MALD looks like a missile, but instead of an explosive payload, it carries a Signature Augmentation Subsystem (SAS) that can broadcast the radar return of any aircraft in the U.S. arsenal to spoof enemy air defenses into targeting the MALD instead of nearby missiles or aircraft. The latest in-service iterations, the ADM-160C MALD-J, also include a modular electronic warfare capability developed under the name CERBERUS. Much more than a single radar jammer, CERBERUS offers a variety of interchangeable electronic warfare (EW) payloads that can be swapped in and out in less than a minute, allowing for tailored EW attacks for a variety of battlefield conditions.

In other words, the small and expendable MALD-J is capable of fooling enemy air defenses into thinking they’re all sorts of incoming aircraft, and can also jam early warning and targeting radar arrays to further complicate matters for defending forces.

With a range in excess of 500 miles and a new, even more capable iteration (known as the MALD-X) in development, these air-launched decoys can significantly bolster the efficacy of other aircraft and weapon systems. And at around $322,000 a piece, these systems are inexpensive enough to be leveraged in great numbers without breaking the bank.

As just one hypothetical use-case, these two efforts alone would allow a very small number of A-10s and cargo aircraft like the C-17 to deploy a massive amount of decoys, jammers, and firepower in the event of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. As Chinese warships attempted to ferry troops across 100 miles of the Taiwan Strait, a fleet of just four C-17s and four more A-10s could lob 64 jamming decoys and 180 long-range anti-ship missiles from 500 miles away, overwhelming air defenses and wreaking havoc on the Chinese fleet before a single fighter, bomber, or done has even flown a sortie.

IF IT’S NOT CHEAP, IT BETTER BE MODULAR

Of course, all of this focus on low-cost volume doesn’t change America’s affinity for advanced (and supremely expensive) platforms, and even this shift toward advanced drones can’t change that. Some of the most expensive uncrewed platforms to emerge in the coming years will almost certainly evolve out of today’s Combat Collaborative Aircraft (CCA) efforts to field AI-enabled drone wingmen to fly alongside America’s top-tier fighters.

These drones will carry a variety of payloads and take their cues from advanced fighters like the Air Force’s Next Generation Air Dominance fighter, the Navy’s F/A-XX fighter, and the forthcoming Block 4 F-35. These drones will extend the sensor reach of their crewed fighters by flying out ahead, carrying electronic warfare equipment to jam enemy defenses, deploying air-to-ground and even air-to-air munitions on behalf of the crewed fighter and more – effectively turning every one piloted fighter into an entire formation unto themselves.

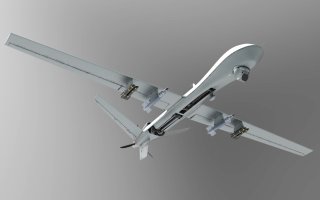

A number of firms are currently competing for a piece of the CCA enterprise and many of these efforts remain shrouded in a veil of secrecy, but one program that has been revealed to the public that we can use as an example is Boeing’s Australia-led MQ-28 Ghost Bat. This 38-foot UCAV operates like any other fighter and offers a range of more than 2,000 nautical miles (more than 2,300 miles).

Like other CCA platforms, the MQ-28 is designed to accommodate and rapidly swap out modular payloads, allowing the aircraft to serve in a variety of rules with a very short turnaround. This ability can give commanders in-theater more flexibility in deciding how best to leverage the UCAVs, but more importantly, it will also allow for rapid updates and upgrades as new technologies emerge.

Arguably, the most important part of this endeavor is the artificial intelligence required to operate these aircraft. The U.S. Air Force is already hard at work developing multiple AI Agents (as they’re called) for this role, with one specially modified F-16, dubbed the X-62A, completing its first air combat exercises with AI in control last December. This year, six additional and fully combat-coded F-16s are being modified to accommodate AI pilots as part of the Air Force’s Project VENOM to further mature the concept.

These AI-enabled F-16s will fly in a variety of exercises and combat simulations with human pilots onboard, so the artificial intelligence can learn directly from human operators how best to manage aviation tasks with increased complexity, culminating in what will eventually be nearly autonomous platforms that can execute complex orders as delivered by a human operator in a nearby stealth fighter.

THE FUTURE MAY BE ABOUT DRONES, BUT PILOTS AREN’T GOING ANYWHERE

Despite rapid advances in AI and automation, as well as the Pentagon’s renewed focus on low-cost combat drones, human pilots will still play an integral role in American air combat operations for years to come. Even the most advanced AI-enabled platforms are still being designed to be effectively operated by human pilots in nearby fighters. Rather than thinking of these drones as autonomous warfighters, it might be more apt to think of them in the same way we might think of a sensor pod carried underwing. Ultimately, these programs, systems, and platforms are being designed to serve as weapons in the hands of the modern warfighter, rather than as replacements for the warfighters themselves.

But while the United States has long used technology as a force multiplier, these new efforts will finally allow for the use of that term in a very literal sense.

To return to the World War II comparison, aircraft of that era may have required fewer man-hours to build… but a single B-29 Super Fortress required a crew of 10-14 to operate. In the not-too-distant future, that ratio will be turned on its head, with just one or two human operators controlling five, 10, or even more platforms simultaneously.

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

This article was first published by Sandboxx News.

Image: Shutterstock.