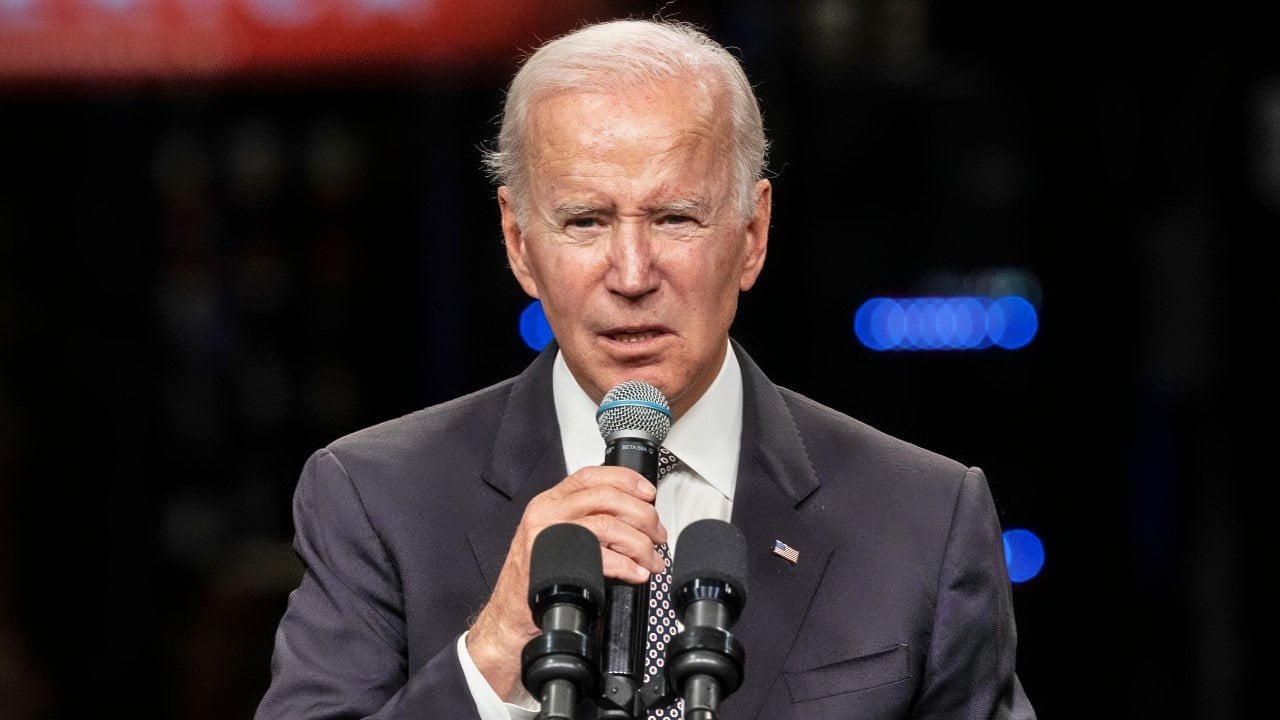

Does Joe Biden Have a Deterrence Problem?

Would you be deterred by an antagonist you believe to be incompetent, irresolute, or both? That question has become part of daily discourse about U.S. foreign policy, if seldom phrased in such stark terms. Contemporary events—in particular Russian aggression against Ukraine and the rise of a domineering China—explain why.

Would you be deterred by an antagonist you believe to be incompetent, irresolute, or both? That question has become part of daily discourse about U.S. foreign policy, if seldom phrased in such stark terms. Contemporary events—in particular Russian aggression against Ukraine and the rise of a domineering China—explain why. The past couple of years, for example, it has become commonplace for rightward-leaning politicians to claim that the U.S. military’s flight from Afghanistan in August 2021 egged on Russian president Vladimir Putin to order the invasion of Ukraine mere months later, in February 2022.

Exhibit A: On the eve of war former president Donald Trump told Fox News: “How we got here is when [Putin and Xi Jinping] watched Afghanistan, and they watched the most incompetent withdrawal in the history of probably any army let alone just us. . . .” Trump contended that the Eurasian despots “watched that, and they said: ‘What’s going on? They don’t know what they're doing.’ And all of a sudden I think they got a lot more ambitious.”

Exhibit B: At a press conference on the day of the invasion, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell lambasted the Biden administration in similar terms: “I think the precipitous withdrawal from Afghanistan in August was a signal to Putin, and maybe to Chinese president Xi as well, that America was in retreat. That America could not be depended upon.” The bottom line for Senator McConnell: “A combination of perception of weakness, and yearning for empire, is what led to the war in Ukraine.”

Now, clearly some of this is political expediency. It suits Republican magnates’ political interests to blame a Democratic administration for seismic misadventures like the Russian onslaught. And to be sure, it’s impossible to state with any measure of confidence that the Afghanistan pullout emboldened the Kremlin. Putin & Co. have no incentive to reveal the inner workings of Russian policy and strategy, for fear of handing the United States and NATO an advantage in some future imbroglio. So they will keep mum.

Someday, maybe, researchers will unearth evidence that Trump and McConnell were right or wrong about Russian calculations heading into February 2022. A future, more open Russian government might allow a peek into the state archives, or make key figures in these events available for interviews. But that will be far too late to inform policymaking in Washington DC today. Trump’s and McConnell’s claims about cause and effect between Afghanistan and Ukraine remain unproven.

We just don’t have the evidence to make a firm ruling one way or the other.

All of that notwithstanding, the Biden administration’s critics do have a point. Just ask another Republican magnate, the late Henry Kissinger. In his treatise The Necessity for Choice, Kissinger contends that there is a “paradoxical consequence” to deterrence. Namely that its success turns on “essentially psychological criteria” rather than brute military might. The point of warfare is to win. The point of deterrence is to make some course of action that a potential aggressor is contemplating—and that we want to deter—the least attractive of all courses of action open to the aggressor.

If an adversary’s leadership believes we can and will carry our deterrent threat, deterrence should hold.

But there are no guarantees. Human beings are fallible, and the human beings who make up the hostile leadership are the ones who decide whether they are deterred. Kissinger declares that deterrence “ultimately depends on an intangible quality: the state of mind of the potential aggressor.” He goes on to state that “a seeming weakness will have the same consequences as an actual one.” In a perverse sense, that is, we have a weakness if an adversary espies one—regardless of whether that weakness exists in reality.

Kissinger being Kissinger, he is able to reduce this murky phenomenon blending psychology with military might down to a simple formula to help us think things through. “Deterrence,” he writes, “requires a combination of power, the will to use it, and the assessment of these by the potential aggressor.” He adds that deterrence is a product of multiplying these three factors—capability, resolve, belief in our capability and resolve on the part of the aggressor—not adding them.

That makes a major difference in how we understand deterrence. “If any one of [the factors] is zero, deterrence fails,” Kissinger concludes glumly. That’s Algebra I. Multiply the biggest number by zero and you get zero. No amount of military power can deter unless political and military leaders are prepared to use it; no amount of resolve can deter without the military power to carry out the deterrent threat; neither physical might nor political willpower can deter unless the aggressor’s leadership is a believer in our capability and our will to use it.

Perception is king.

It’s worth pointing out, as Kissinger does not, that competence is central to capability. Capability is more than hardware. The finest weapon is no better than its user. As Admiral Bradley Fiske observed a century ago, only human excellence can unlock the full design potential of hardware. Hand an untrained or unmotivated soldier the latest in gee-whiz military technology and he will accomplish little on the battlefield. Hand a trained, motivated, competent soldier that same widget and he will accomplish much. The human factor matters—and how others assess the state of it could make the difference between failure and success in efforts to deter.

Sage foreign leaders, then, will take the measure of U.S. physical power and human proficiency when gauging how seriously to take deterrent threats issuing from Washington.

As an aside: Kissinger doesn’t carry his perceptual logic further, but we can. What he says about deterrence applies just as much to coercing antagonists and to reassuring allies, coalition partners, and bystanders we would like to recruit to our cause. If deterrence is about dissuading an opponent from undertaking some course of action it would like to take, coercion is about convincing an opponent to do something it would prefer not to do. Giving heart to allies and friends is about making a commitment to them and displaying the capability and resolve to keep that commitment. All three diplomatic domains involve molding perceptions among foreign governments, societies, and armed forces, hostile, friendly, or indifferent.

Reputation is everything.

Here endeth the theoretical excursion. Back to Trump and McConnell. The two Republicans’ critiques are subtly different. President Trump longed to exit Afghanistan during his presidency, so he could hardly rebuke President Joe Biden for going wobbly on whether to stand by an ally. So the ex-president alleged incompetence on the part of Biden’s Pentagon leadership. His point being that a Putin or Xi could well come to doubt the capability element of American martial strength. Rightly or wrongly, Putin or Xi could reason that, if U.S. forces botched the withdrawal from a struggle against a woefully outmatched foe, they would be incapable of executing far more forbidding missions such as halting aggression against Ukraine, or repulsing a Chinese assault in the Taiwan Strait or China seas.

Despite world-beating U.S. military technology, in other words, Moscow or Beijing could come to disparage U.S. military effectiveness. If so, Kissinger’s belief variable could drop to zero, driven down by hostile capitals’ perceptions of U.S. military incompetence. Perceived American weakness is weakness in the minds of Putin, Xi, and their lieutenants, and that’s where deterrence does or doesn’t work.

McConnell leveled the same charge as Trump with regard to incompetence while also questioning the Biden administration’s resolve to uphold its commitments not just to Afghanistan but to other allies. Hence his claim that Putin might well see America as being in retreat around the world—including in Russia’s near abroad. McConnell’s indictment was more damning than Trump’s because it faulted the administration not just for incompetence, which suppressed Kissinger’s capability variable, but also for political fecklessness, which suppressed the resolve variable.

If so, all three variables in Kissinger’s formula collapsed. Disbelief in U.S. power and resolve may well have suggested to Putin that he had permissive surroundings for maneuver in Eastern Europe. The United States and NATO neither could nor would stand against cross-border aggression. Why not roll the iron dice?

So Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell advanced a hypothesis about power and perception that, while unproven in this particular instance, is well-grounded in military theory. The U.S. armed forces and their political masters must burnish America’s reputation for martial prowess—or see deterrence fail again and again.

About the Author: Dr. James Holmes

Dr. James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College and a Nonresident Fellow at the University of Georgia School of Public and International Affairs. The views voiced here are his alone.