Explained: Why Hypersonic Missiles Are Such a Big Deal

Every great power both covets and fears them.

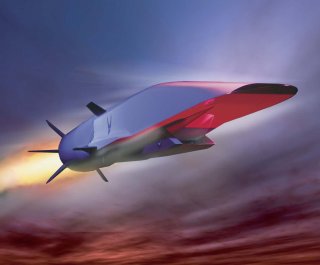

They unleash destruction traveling at five times the speed of sound. They maneuver with computerized precision while descending back into the earth’s atmosphere toward a target. Their speed and force is so significant, they can inflict damage by sheer “kinetic” impact without needing explosives.

They can destroy Navy ships, air defenses, ballistic missiles, ground targets and aircraft in a matter of minutes or even seconds, depending upon the launch point—seemingly coming out of nowhere.

They are hypersonic weapons.

Many senior Pentagon weapons developers share a common view. They fear that hypersonics are nearly impossible to defend against and believe they will usher in an unprecedented tactical reality bound to reshape warfare and force unforeseen strategic adaptations.

How can carrier strike groups project power within striking range of enemy targets? How can mechanized armored columns maneuver without being badly crippled by a hypersonic attack? How can the most advanced fighter jets avoid impact if there simply is no time?

Perhaps satellites, nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles and defensive weapons such as ground-based interceptors could also be vulnerable? The variables through which hypersonics promise to alter warfare are seemingly limitless. The danger is extremely serious.

But what if there were a viable way to defend against hypersonic weapons? What if they could be destroyed or disabled before hitting a target?

This, according to Pentagon and industry weapons developers, is actually possible. In fact, U.S. weapons developers are already working on it. Raytheon is among a group of industry innovators looking at ways to counter hypersonic attack through advanced sensing technology.

“Getting to the “high ground” is imperative. Lower earth orbit constellations will improve hypersonic detection and tracking capability of hypersonics. From space, sensing is not limited by the curvature of the earth,” Erin Kocourek, Raytheon’s RMD hypersonics/counter-hypersonics lead, told TNI in an interview.

New satellites are indeed an essential part of this equation, according to MDA leaders who say the Pentagon is looking to space sensors to counter hypersonic attack.

“We have to work on sensor architecture, because they do maneuver and they are global, you have to be able to track them worldwide and globally. It does drive you towards a space architecture, which is where we’re going,” Navy Vice Admiral Jon Hill, director of the Missile Defense Agency, said in a Pentagon report.

The Missile Defense Agency and the Space Development Agency, Hill said, have already built a satellite prototype and plans to put up more new satellites to better track hypersonic attacks over the next few years.

“As ballistic missiles increase in their complexity ... you’re going to be able to look down from cold space onto that warm earth and be able to see those,” Hill said. “As hypersonics come up and look ballistic initially, then turn into something else, you have to be able to track that and maintain track. In order for us to transition from indications and warning into a fire control solution, we have to have a firm track and you really can’t handle the global maneuver problem without space.”

“Raytheon is making investments in hypersonics, aimed at better understanding the threat, and modeling how to advance an entire layered system of terrestrial sensors, C2, space sensors and effectors to detect, track and engage these weapons,” Kocourek said.

The fundamental challenge with hypersonic flight resides in this need to manage the extreme temperatures reached at those speeds, factors which can prevent, complicate or disable successful hypersonic flight.

An area of focus within this sphere of inquiry, AFRL developers tell TNI, relates to several complex aerodynamic challenges, such as managing the airflow surrounding the vehicle in flight.

Referred to by scientists as a “boundary layer,” the airflow characteristics of a hypersonic weapon’s flight trajectory greatly impact the stability of the system. Moreover, much of which relates to temperature.

“We are looking to employ disruptive technologies that will cause the adversary’s hypersonics to lose momentum,” Kocourek.

The science of airflow boundary layers is extremely complex, yet it does align with several key aerodynamic concepts related to hypersonic flight stability. Simply put, engineers are looking to create advanced hypersonic weapons that generate a “laminar” or smooth airflow boundary layer, as opposed to a “turbulent” airflow.

The more movement, mixing or agitation in the airflow surrounding the air vehicle in flight—often consisting of movement or particle collisions in the airflow—the more turbulent it becomes. This is according to an essay from the University of Sydney’s School of Aerospace, Mechanical & Mechatronic Engineering.

“A boundary layer may be laminar or turbulent. A laminar boundary is one where the flow takes place in layers...each layer slides past the adjacent layers.

This is in contrast to turbulent boundary layers, where there is intense agitation,” the 2005 essay states.

Of particular significance, the essay explains that turbulent boundary layers generate very high “heat transfer rates.”

“Packets of fluid may be seen moving across (in turbulent boundary layers). Thus there is an exchange of mass, momentum and energy on a much bigger scale compared to a laminar boundary layer,” the University of Sydney essay states.

Kris Osborn is the new Defense Editor for the National Interest. Osborn previously served at the Pentagon as a Highly Qualified Expert with the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army—Acquisition, Logistics & Technology. Osborn has also worked as an anchor and on-air military specialist at national TV networks. He has appeared as a guest military expert on Fox News, MSNBC, The Military Channel, and The History Channel. He also has a Masters Degree in Comparative Literature from Columbia University.

Image: Reuters