F-111: The Air Force Warplane Built To Kill Everything (Everywhere)

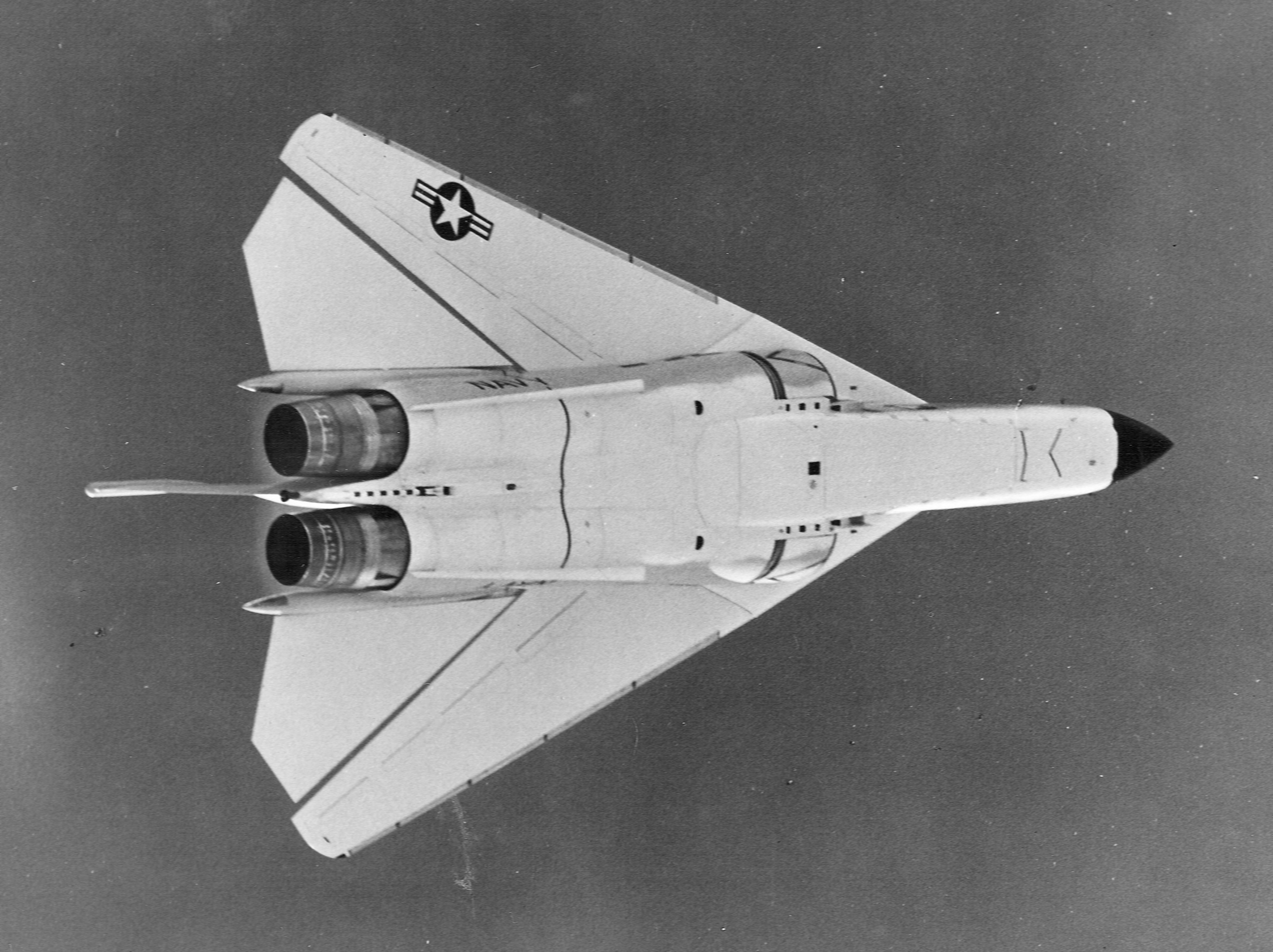

The F-111 Aardvark, developed in 1962 by General Dynamics, was a groundbreaking warplane with swept wings and advanced radar systems, allowing it to fly at supersonic speeds and low altitudes.

Summary and Key Points: The F-111 Aardvark, developed in 1962 by General Dynamics, was a groundbreaking warplane with swept wings and advanced radar systems, allowing it to fly at supersonic speeds and low altitudes.

-Initially intended as a fighter for both the USAF and the Navy, it was repurposed for deep strike missions after the Navy deemed it unsuitable.

-The F-111 saw significant action in the Vietnam War, Libya, and Operation Desert Storm, proving its worth despite early flaws.

-Its operational success led to international adoption, and its last flight was in 2010 by the Australian armed forces. The Aardvark's speed and versatility offer lessons for future aircraft design.

F-111 Aardvark: The Supersonic Warplane That Redefined Combat

File this under “They Don’t Make ‘Em Like They Used To.” The F-111 Aardvark was a history-making warplane. Developed in 1962 by General Dynamics, this warbird had a unique design and an even more exciting service record. With swept wings, she could hit the wild blue yonder in as little as 2,000 feet (when her wings were fully extended, that is). When those wings were fully retracted, the great warbird could blast along at supersonic speeds. In fact, the Aardvark made history as the fastest-flying plane at a low altitude.

Thanks to its advanced (for its time) “terrain-hugging” radar system, the plane could fly at extremely low altitudes and achieve supersonic flight without much risk of hitting anything. At higher altitudes, she could break easily into Mach 2.2. Further, the F-111 could make transoceanic flights without needing to refuel.

The F-111 Aardvark was ahead of its time and packed quite a punch in combat, having seen much service in the Vietnam War.

F-111: Not What the Pentagon Intended

Interestingly, the F-111 was originally intended as a fighter for both the United States Air Force and the United States Navy. It cost $75 million in 1964 (or about $750 million today). Upon completion of the craft, however, the Pentagon’s brass found that the aircraft was unacceptable for its intended use. Therefore, the Navy backed out entirely from the program (although the failure of the Aardvark led to the design of the F-14 Tomcat, probably the Navy’s greatest plane ever made).

The Air Force, however, determined that the supersonic plane could be used for something else: deep, penetrating strikes into enemy territory. This was the F-111’s experience in Vietnam, against Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, and in Operation Desert Storm.

In fact, the Air Force’s fateful decision to accept the plane but to re-task it as a bomber changed history. This is a case of the Pentagon in the early days of the Cold War being far more innovative and cost-effective in its acquisitions than it ever could be today. The Air Force turned a failure into a long-term win with the Aardvark. The Navy’s loss, then, was the Air Force’s—and America’s—gain. Rather than scrap the whole project and basically burn the U.S. tax dollars that went into making it, the Air Force recognized that this plane could be used in far more unique ways than it was intended to have been deployed.

The F-111 got its nickname, “Aardvark,” because, like the African animal of the same name, the F-111 travels close to the ground, hunting its prey. In 1966, the Aardvark set the record for the longest, low-flying flight at supersonic speeds. From that point on, the Air Force knew it had a diamond in the rough. Despite its potential, when the Aardvark was first deployed to Vietnam in 1968, it performed terribly due to a wing stabilizer flaw. The Air Force had to withdraw all its Aardvarks from the fight. Many at the time believed the F-111’s days were numbered. But the stabilizer problem was soon rectified.

A Decades-Long Operational Success Story

By 1972—during Operation Linebacker—the Aardvark was redeployed and led the way in dangerous night bombings in which the supersonic planes skimmed the tops of the dense jungles just below. The Aardvark had proven itself after an inauspicious start. The Aardvarks were used brilliantly to soften up North Vietnamese air defenses that would have otherwise been deployed against the Air Force’s far more valuable B-52 Stratofortress bombers. The Aardvarks had one of the best performance ratings in Vietnam once that stabilizer problem was repaired.

Of the 4,000 missions that the F-111 flew in the unfriendly skies above Indochina, only six units were lost.

Ultimately, the F-111 went international. Britain and Australia ended up purchasing variants of this warplane. The Australians had a special variant—the F-111C—unique only to their armed forces. The final flight of the F-111 as a combat plane took place in 2010. However, it was not piloted by the Americans who had built her but rather by the Australians who had come to love the plane.

F-111: An Inspiration for the Future of American Air Power?

The F-111 Aardvark was quite literally able to outrun whatever air defenses it faced. And this is a key feature that plane manufacturers should consider today when designing next-generation warplanes. Stealth is, of course, a massively helpful feature that most new American warplanes and bombers are incorporating.

But there’s something to be said about building a plane that can simply go faster than the defenses that an enemy can deploy. With advances in detection technology and the rise of sophisticated anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities, the Pentagon might want to stop prioritizing stealth and start amplifying the speed of its next-generation fighters and bombers.

About the Author

Brandon J. Weichert is a former Congressional staffer and geopolitical analyst who is a contributor at The Washington Times, as well as at American Greatness and the Asia Times. He is the author of Winning Space: How America Remains a Superpower (Republic Book Publishers), Biohacked: China’s Race to Control Life, and The Shadow War: Iran’s Quest for Supremacy. Weichert can be followed via Twitter @WeTheBrandon.