The Irony in Being Unable to Explain Irony

What makes something ironic?

Have you ever found yourself about to say, “that’s ironic,” only to stop yourself – unsure whether you were using the word correctly?

If you’re like most people, you probably know irony when you see it, but can’t really explain it. Part of the confusion might have to do with the myriad ways the word is deployed.

It can be used in speech. Sometimes it’s used to describe an attitude. Other times it’s used to describe a situation. In many cases, it’s simply used incorrectly.

In short, irony is complicated.

In my recently published book, “Irony and Sarcasm,” I attempt to disentangle knotty issues like these.

In general, irony refers to a clash between expectations and outcomes. Typically, the outcome is the opposite of what someone wanted or hoped for. It’s ironic, for example, when your boss calls you into her office, and you’re expecting a promotion, but you instead find out you’ve been fired.

This clash carries over to verbal irony, in which people say the opposite of what they literally mean. But such expectations are subjective, and verbal ironists don’t always mean the exact opposite of what they say. Insulting someone by saying they’re the most intelligent person on Earth, for example, doesn’t mean they are the least intelligent; it just means they’re not all that bright.

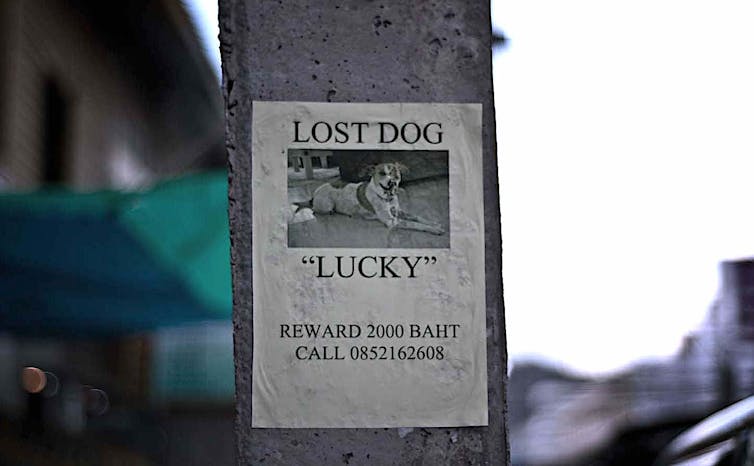

Some cases, however, are relatively straightforward. Consider situational irony, in which two things become odd or humorous when juxtaposed. A photo of a sign in front of a school with a misspelled word – “We are committed to excellense” – went viral. And the January 2020 rescheduling of an annual snowball fight at the University of British Columbia was correctly described as ironic because of the reason for the cancelation: too much snow.

In other cases, however, a situation may lack an essential element that irony seems to require. It’s not ironic when someone’s home is burglarized, but it is if the owner had just installed an elaborate security system and had failed to activate it. It’s not ironic when a magician cancels a show due to “unforeseen circumstances,” but it is when a psychic’s performance is canceled for the same reason.

In 1996, Alanis Morissette was roundly criticized by pedants who argued that the examples of situational irony in her song “Ironic” – “It’s like rain on your wedding day” – were not, in fact, ironic.

Warnings abound in dictionaries and style guides. “The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage,” for example, warns that “not every coincidence, curiosity, oddity and paradox is an irony even loosely.”

One reason that irony is so confusing is that the word also refers to a certain perspective or style: one that is detached, aloof and seemingly world-weary. This affectation is often referred to as the “ironic attitude” and has come to be associated with adolescents or young adults.

Following 9/11, many pundits announced the “death of irony,” arguing that a frivolous and flippant attitude, often described as ironic, was out of step with the times.

If this were true, irony didn’t stay dead for long. In fact, the ironic attitude has been declared dead with almost every change in recent American politics. In 2008, Joan Didion worried that Barack Obama’s election was fueled by a naïve belief in “hope” that would transform the country into an “irony-free zone.” Washington Post columnist Dana Milbank wrote in 2019 that Donald Trump’s hypocrisy has – once again – killed irony.

Of course, irony is not the only problematic word in English. Some terms are used so inconsistently, and arouse such strong feelings about proper usage, that people begin to avoid using them out of fear of appearing uneducated. The lexicographer Bryan Garner has referred to such words as “skunked.”

As an example, Garner cites “transpire.” Purists maintain that it refers to things that become known only gradually over time. However, “transpire” is now frequently used to simply indicate that something has happened – the nuance of “over time” has become lost. “Hopefully” is another example. Purists maintain that it should only be used to mean “in a hopeful way” – “He looked hopefully in her direction.” However, it is frequently employed to mean “it is hoped that” – “Hopefully, she’ll look in his direction.”

Many dictionaries contain explicit warnings about using such words in these more common yet less accepted ways. Careful users of language are hesitant to use the newer – and typically broader – uses of terms before they’ve become firmly established. Until then, they’re skunked.

Is irony in danger of becoming skunked? Perhaps.

The life histories of words are difficult to forecast, and terms go in and out of fashion in unexpected ways. Irony is an incredibly useful term that is applied to a very nebulous set of concepts.

Its unique versatility, however, may prove to be its undoing.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

![]()

Roger J. Kreuz, Associate Dean and Professor of Psychology, University of Memphis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters