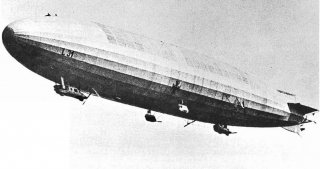

Meet the LZ 104 (L.59)—the German Zeppelin That Took Part in a Secret Mission

Utterly amazing.

When the First World War broke out in August 1914 many in colonial German East Africa (modern day Tanzania) had hoped the war would be over quickly, and there were those who hoped the region would be declared neutral. That wasn’t to be, and instead of staying out of the war a small German force led by Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck led a successful guerrilla campaign that tied down hundreds of thousands of British, South African, Indian, Belgian and Portuguese troops.

From the outbreak of the war Lettow-Vorbeck realized that he couldn’t wage a direct attack against the superior British forces. Instead he launched raids in British East Africa (Kenya), British Rhodesia, and the Belgian Congo.

His “Schutztruppe,” which was made up of some 3,000 German troops, including sailors from the light cruiser SMS Königsberg, and 11,000 Askaris (native troops serving the Germans as soldiers as well as bearers), marched thousands of miles.

His efforts in tying down Allied troops that were badly-needed on the Western Front were so successful that the German military high command considered ways to reinforce his slowly diminishing force. Sending men and material by ship was out of the question. The British had uncontested control of the seas, and while perhaps a U-Boat could get through, Lettow-Vorbeck’s movements were limited largely inland and away from the Indian Ocean.

Thus was born Operation “China-Sache” (“China Snow”), and it involved sending a zeppelin that would launch from German-allied Bulgaria, cross over Greece, fly across the Mediterranean Ocean then over Entente-held Egypt. It was a daring plan, but airships had already been used to make long-range strikes against England—resulting in the so-called “Zeppelin Terror.”

The German manufacturer Lufschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH offered its news airship LZ 104 (construction number), designated L.59, for the mission. Dubbed the Afrika-Schiff (“Africa Ship”), it was 743-feet-long and had a top speed of 64mph, and carried a crew of twenty-one. It also had an onboard wireless radio that allowed the crew to remain in contact with the Germany military.

When the airship left Yambol in Bulgaria on November 4, 1917 it began a planned journey that was longer at the time than any aircraft had ever flown. But it was always intended to be a one-way mission, and at the end of a planned four day flight, the crew would simply join Lettow-Vorbeck’s ragtag Schutztruppe.

More importantly, the fifteen tons of cargo included machine guns, ammunition, food, medical supplies and even Iron Cross medals to be awarded to the troops fighting in East Africa. In addition, the airship’s canvas canopy could be converted to tents, its internal fabric would serve as bandages and the aluminum frame was to be reassembled as a radio tower!

The journey was far from pleasant; the air was bumpy, especially over open water, while the heat over the desert and freezing nights created violent turbulence.

The problem became even more worrisome when one of the five engines seized up during the journey. But a bigger issue was the loss of power, which meant the radio could only receive signals and was rendered incapable of transmitting. Despite these hardships, Kapitänleutnant Ludwig Bockhold, a German naval officer who commanded the mission, pressed on.

At the halfway mark, just west of Khartoum in the Sudan, the airship received a coded message that it was to return to base. Lettow-Vorbeck had signaled Berlin that the landing zone in German East Africa at Mahenge was under heavy fire.

Despite protests from the crew the L.59 headed back for Bulgaria. While it hadn’t successfully completed its mission it still had traveled 4,200 miles non-stop in less than ninety-five hours—and had fuel for another two-and-half days. The flight broke the records for both distance and endurance.

Lettow-Vorbeck marched his army south to Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique), and captured the town of Ngomano. For the next year the man who would be known as the “Der Löwe von Afrika” (“Lion of Africa”), marched his force throughout eastern Africa. He continued his campaign until he received news of the Armistice on November 23, 1918—more than a week after the hostilities ended on the Western Front. He surrendered at Abercorn, Rhodesia and was the only German commander to march through Berlin undefeated in battle.

As for the L.59, it continued to fly bombing and reconnaissance missions in Southern Europe until it exploded unexpectedly during a mission to bomb the British naval base at Malta on April 7, 1918 killing the crew of twenty-one including Bockholt. Her loss was attributed to an accident.

Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers and website. He is the author of several books on military headgear including A Gallery of Military Headdress, which is available on Amazon.com.

Image: Wikimedia.