The U.S. Air Force's Light Fighter 'Dream' Has Problems

Air Force Chief of Staff General David Allvin has suggested a shift away from the costly, long-lasting fighter programs like the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) fighter in favor of more adaptable, smaller, and cheaper modular aircraft.

Building the ‘Minuteman III’ of fighters

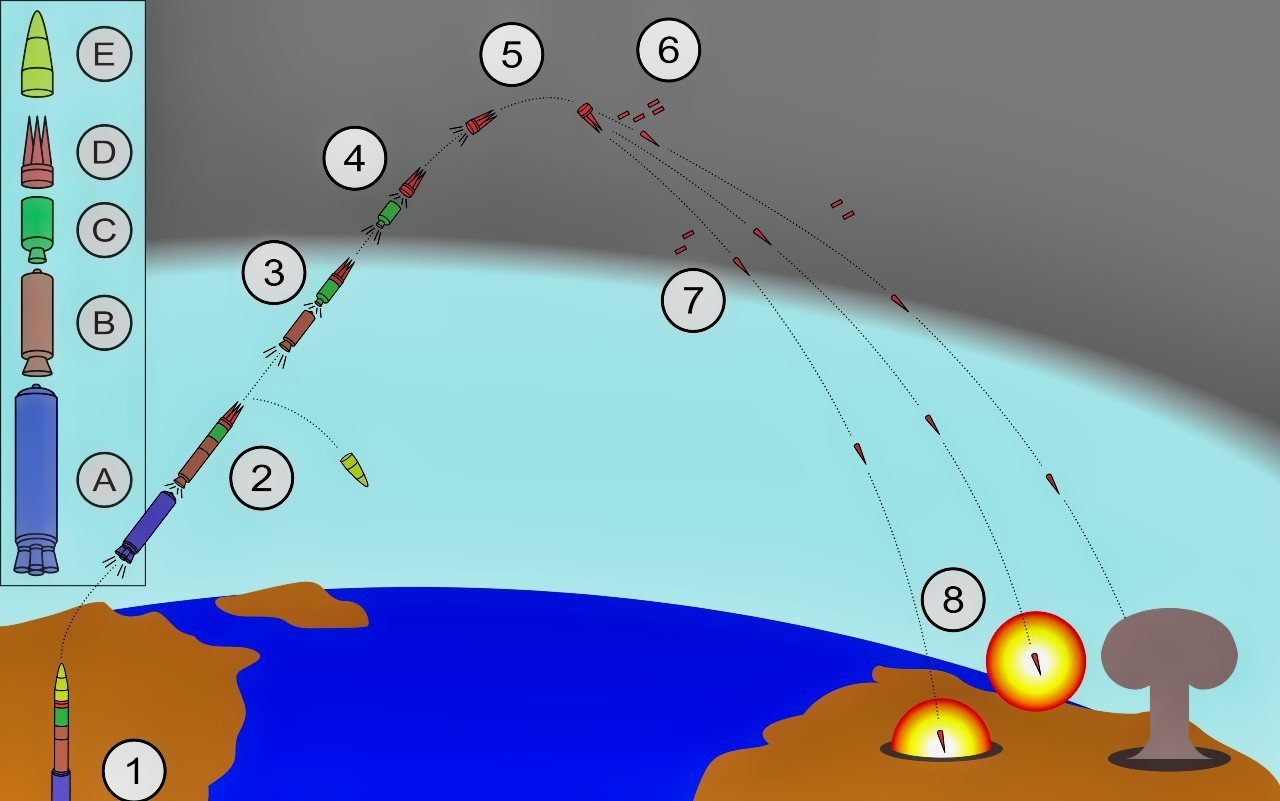

The LGM-30G Minuteman III ICBMs America operates as its land-based nuclear deterrent today started entering service all the way back in 1970 with a projected ten-year service life, meaning they were slated to be replaced by newer and more modern weapons starting in 1980. Its intended replacement, eventually known as the LGM-118A Peacekeeper, didn’t make its first test flight until 1983, with the first ten weapons reaching service in 1986.

However, the shifting geopolitical landscape following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the subsequent Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) II signed in 1993, saw only 50 Peacekeepers ever built — all of which were subsequently retired by 2005. As a result, the United States has spent billions trying to keep its aging Minuteman IIIs viable decades after their intended lifespans, and now has acknowledged that they’ve reached the point where it’s no longer feasible to keep them in service.

As a result, the Air Force now has no choice but to swallow the ballooning cost of this program as it’s nearly doubled in budget over the past few years, simply because the missiles that were initially meant to serve for roughly ten years will now be on duty beyond their 60th birthday.

And while missiles and fighters are certainly not the same types of programs, the lack of data we have to pull from to inform a decision about short-lifespan fighters leaves us with few places to look outside the confines of Air Force acquisitions in recent decades — which are, of course, informed by the contemporary politics surrounding these decisions.

The fact of the matter is, awarding a production contract for any fighter (or really, any military platform, for that matter) is — to some extent — a gamble. The Pentagon may know how well the prototypes and technology demonstrators perform, but it’s betting on the winning firm to be able to mass produce the same capabilities for a projected cost. It’s betting that there won’t be any significant unforeseen technical challenges once the platforms reach the field, betting on continued Defense priorities throughout the production run, and maybe the biggest gamble of all… it’s betting on continued political support for years or even decades as a design on a sheet of paper matures into an operational fleet of platforms.

And while the idea of rapidly adaptable fighter designs meant to be thrown away every ten years does sound incredibly promising, actually executing such a dramatic shift in acquisition will require an immense amount of political and industrial buy-in — something that won’t come easily without a clear upside for both parties. But even if that can be accomplished quickly enough to field a new air superiority fighter in the early 2030s, when even upgraded F-22s will be starting to get pretty long in the tooth, that wouldn’t be the end of the challenge.

The Air Force would almost invariably find itself having to argue to justify the purchase of a new slew of fighters in the 2040s, as lawmakers question whether the jets designed to last for only one decade really need to be replaced after all, with many arguing that swapping out modular systems should be sufficient to maintain its competitive edge. Then, the debate would begin anew in the 2050s, the 2060s, and so on, with the concept’s efficacy teetering in the balance every time.

Unlike the Minuteman III, which was originally slated for just a ten-year service life, the LGM-35A Sentinel is expected to stay in service for better than a half-century, because the Air Force has no intention of making the same mistake twice with these long-range munitions. It’s well aware of the fact that fielding ICBMs that would need replacements ten years down the road assumes funding for those replacements will be forthcoming, and in today’s political climate, that’s an awfully big assumption.

And yet, because of the Sentinel’s immense cost overruns, the NGAD program now runs the risk of becoming the fighter equivalent of the Minuteman III itself — a system meant to serve for 10 years, but dragged down the road for decades as officials and lawmakers try to dodge the sticker-shock of fielding a replacement until they have no other options left.

And then, when that program goes 81 percent over budget before the first aircraft is even delivered the way Sentinel has, Defense officials would be forced to echo the same talking points about how the strategic need for replacement outweighs the economic impact of cost overruns.

Cultural inertia in the fighter business

So, does this idea of fielding lower-cost fighters more frequently make sense? In a lot of ways, it definitely does, and to be clear, this is very much the design methodology being employed for a variety of unmanned platforms like the collaborative combat aircraft (CCAs) currently making their way toward service.

But big-ticket acquisitions like fighters, bombers, and warships are subject to far more than military considerations — they’re the subject of immense public scrutiny and lawmaker debate that can span decades, and when it comes to the court of public opinion, there are no guarantees that extend beyond the end of the week, let alone the end of the decade.

It’s not impossible that such a concept could work, and if Uncle Sam could pull it off, it might make for the most incredible series of tactical aircraft this world has ever seen… But in today’s political world, it seems like a miracle when lawmakers can come together and agree to fund a tent-pole program like air superiority fighters… And it seems dangerous to bet on that miracle happening on schedule, over and over again, as each tranche of new fighters begins development.

The most optimal solution might truly be found in the lineage of the “light fighter” terminology itself, which was famously attributed to the F-16 program as a means to provide America’ with sufficient fighter capacity when it became clear the Air Force couldn’t afford to procure F-15s in sufficient numbers to meet the force’s strategic needs. At the time, the Lightweight Fighter Program’s success with the F-16 didn’t see the cancellation of the F-15 it was meant to supplement — and a new “lightweight fighter” meant to supplement the NGAD program could provide similar benefits.

This possibility was even hinted at by Retired Gen. James M. Holmes, former head of the Air Force’s Air Combat Command in 2021, when he said the branch may ultimately field two variants of the fighter to emerge from the NGAD program — one with more range and payload capacity for extended engagements over the Pacific (which would be the pricier of the two), and a separate, smaller (i.e. lighter) design meant for shorter-ranged operations in places like Europe. The use of modular systems and open system software architecture would allow for a great deal of commonality between airframes, reducing the costs associated with standing up two separate fighter production lines… Nonetheless, for a cash-strapped Air Force, this would be a significant challenge.

And of course, with the F-35 still in active production, the arithmetic gets even more complicated.

Some might reasonably argue that the F-35 itself, which now rings in at an average of $82.5 million per runway variant — roughly $7.5 million less than a new F-15EX — is already positioned to fill that “low” end role as compared to the NGAD’s anticipated flyaway costs of some $300 million per airframe. After all, $82.5 million may sound like a lot, but it’s significantly lower than the adjusted prices on some of the previous era’s top-tier platforms like the F-14 Tomcat, which when adjusted to today’s inflation, cost nearly $121 million per unit in 1970s.

But then, in my lifetime we’ve seen things like stealth go from a handful of boutique, specialized and classified airframes that operated in secret and only under cover of darkness, to the F-35 becoming one of the most widely operated fighters on the planet, with more than 1,000 airframes delivered and production expected to continue well into the 2040s to meet demand. There is simply no denying that things are changing — and changing quickly.

So, maybe I’m just being a part of that cultural inertia that such a momentous plan would need to overcome in order to succeed.

About the Author: Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Image Credit: Creative Commons and or Shutterstock.