Why Democrats Should Be Cautious About Breaking Up Big Tech

More than antitrust.

Amid the bipartisan rush to judgment on Big Tech, there was a glimmer of hope in the recent debate among the Democratic presidential contenders: Some pushed back on prejudging tech antitrust cases.

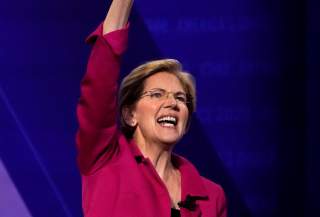

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) is the most aggressive Democratic presidential candidate on antitrust. In March 2019, she laid out a plan for breaking up Amazon, Google, and Facebook. No need for bothersome due process, fact gathering, and expert analysis.

Fortunately, some candidates believe it’s a good idea to think long and hard before potentially destroying companies that billions of people enjoy using every day. Former Congressman Beto O’Rourke, Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), and tech entrepreneur Andrew Yang were skeptical that breaking up the companies would resolve issues raised by tech critics.

There are at least 3 reasons these candidates are right to not make antitrust judgments during a presidential race.

Reason 1: Good antitrust needs facts, analyses, and rule of law

Antitrust is complex, and professionals in the field study cases for months and sometimes years before there are final decisions. And even then, things can go wrong: After years of investigation and litigation, the government dropped its 1969 case against IBM, concluding that the case had no merit. Much of the government’s 2000 case against Microsoft also failed.

What analyses are done? One determines whether a firm has market power, which is a lot more complicated than simply calling them “huge monopolies” as Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) does. Current best practice is to study whether companies can increase prices without losing many customers.

Another analysis determines whether market power is used to harm consumers. This, too, is complicated, as evidenced by the government losing the AT&T and Time Warner merger case despite hiring one of the world’s best antitrust economists.

And antitrust is based on rule of law, not the rule of a candidate. O’Rourke said it well: “I don’t think it is the role of a president or a candidate for the presidency to specifically call out which companies will be broken up.” Or if any will.

Reason 2: Populist arguments make for bad antitrust prosecution

In discussing the presidential campaigns of Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, Harvard professor Marty Linsky explained that campaigns are about pandering to, for example, people’s fantasies (Obama) or preconceived notions (Romney). Calling Big Tech names (Sen. Sanders) or saying they “have too much power — too much power over our economy, our society, and our democracy” (Sen. Warren) is pandering to fears and political angst.

Early antitrust cases in the US were sometimes driven by populist pandering. It was a common rhetorical tool of Louis Brandeis and Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

The result? The cases that the government pressed using populist and personal attacks were costly and didn’t benefit customers. Their consistent failure motivated the adoption of the consumer welfare standard for antitrust in the 1980s.

Reason 3: Current thinking on regulating business models is simplistic

Breakup advocates simply want to make some business models illegal. The rhetoric is that this makes people better off. For example, Sen. Warren believes customers would be happier if Amazon didn’t sell products on its own platform. But she is describing eBay’s business model, and millions of customers choose Amazon over eBay every day.

A fundamental problem is that sometimes antitrust officials, lawyers, and economists treat companies as if they are made of Legos. For example, Sen. Warren believes that unplugging Waze and DoubleClick from Alphabet would leave each piece fully intact. It wouldn’t.

This Legos view of business is a well-worn path in antitrust, and it consistently leads to bad results. When MCI and WorldCom wanted to merge in 1997, regulators worried about market power in the internet backbone. So they required the companies to sell some of their backbone business. But customers didn’t want to be sold and chose to stay with the merged MCI WorldCom.

Net neutrality is based on this Legos view of business. And so is the idea that the government can create a new wireless company by combining Dish Network management with some Sprint employees, T-Mobile’s billing system (for 3 years), T-Mobile’s wireless network temporarily and then a Dish-built network later, possibly some unused Sprint cell sites, etc. If the tech business were that simple, startups would not have a 90 percent failure rate.

What should be done?

Antitrust should remain under rule of law. And those who implement and oversee it should be humble. There were other scary moments during the debate, such as when O’Rourke said the US regulates social media as utilities (it does not) and when Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) said that one of her political rivals (President Donald Trump) should be kicked off Twitter. Hopefully, those were just momentary lapses that won’t become themes.

(Disclosure statement: Mark Jamison provided consulting for Google in 2012 regarding whether Google should be considered a public utility.)

Mark Jamison is a Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

This article originally appeared at The American Enterprise Institute's AEIdeas blog.

Image: Reuters.