Why is the U.S. Navy Running Out of Tomahawk Cruise Missiles?

Firing off more weapons than America buys causes stockpiles to decline quickly. These are the same weapons reserve the nation would need should Beijing seek to use force to take Taiwan while the United States is supporting wars in two other regions.

Beyond America’s snacks, the White House should be worried about the U.S. military’s “shrinkflation” problem. Year after year, inadequate budgets that don’t keep up with inflation cause Pentagon civilians to propose retiring more aircraft than are being delivered to the force, sending more ships to the ghost fleet than are being built, and now firing off more precision weapons than can be replaced anytime soon.

As retaliatory strikes against Iran-backed rebels and terrorists continue, anxiety is rising in Washington. Not just about growing threats but also about dwindling American stockpiles of select munitions and concerns that production lines are “maxed out.”

While concern is widely shared about the rising cost of defense in the Red Sea, a transition to offensive strikes has now raised a similar concern as the U.S. Navy (and Air Force) continue to expend powerful and expensive ordnance on a broad swath of targets.

Recent operations repeatedly deplete years’ worth of missile production overnight.

Since initial strikes began on January 11, Navy ships have repeatedly employed both carrier-launched aircraft and sea-launched Tomahawk cruise missiles to strike Houthi radar, drone, and anti-ship missile sites.

The Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM) is one of the Navy’s premier capabilities and has been a deep strike weapon of choice for many commanders across conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. As a sea-launched cruise missile designed for land attack, it can be fired from submarines or ships with a range of over 900 miles. Tomahawks, therefore, serve as the Navy’s primary land-attack capability without putting aviators at risk.

While the Navy does have a large existing stockpile of Tomahawks to sustain its land-attack capability, it has recently been firing the missiles faster than it can replace them. According to the Navy, opening day strikes alone expended more than 80 Tomahawks to hit 30 targets within Yemen.

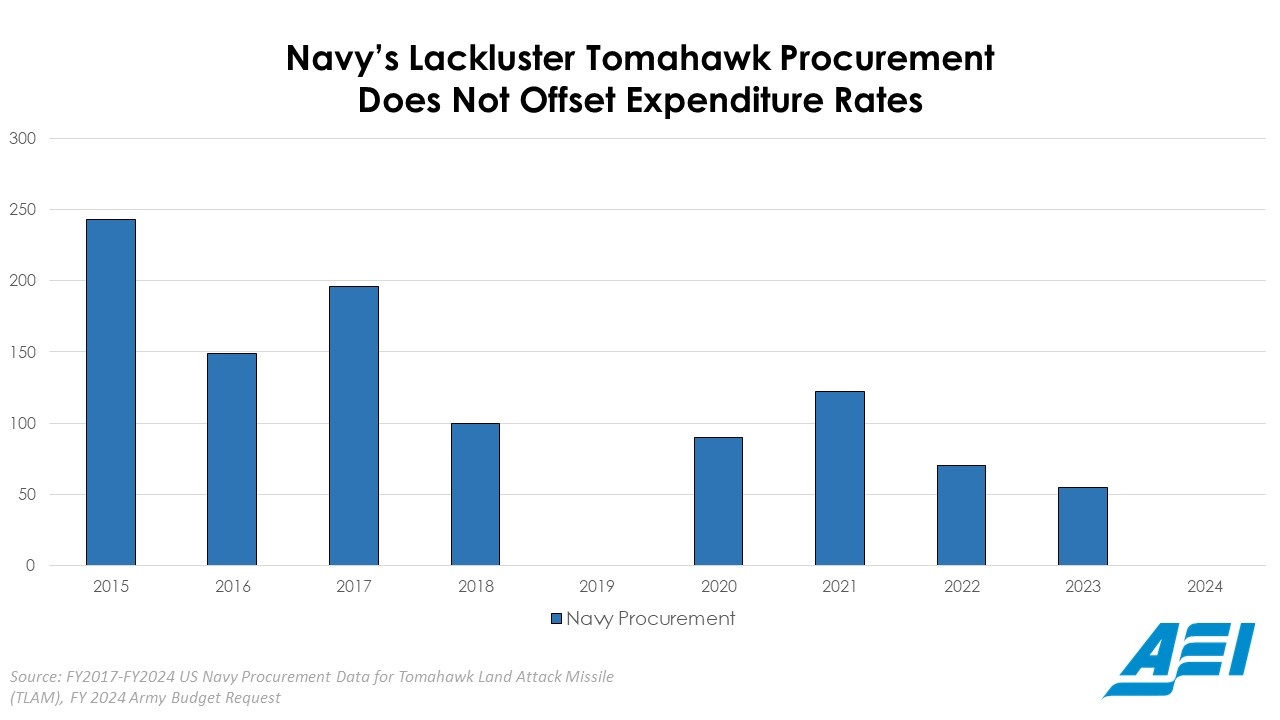

Last year’s entire Tomahawk purchase of 55 missiles accounted for 68 percent of the precision munitions fired at the Houthis in one day. This is an unsustainable rate of expenditure. However, this represents adherence to, rather than deviation from, the norm.

Prior strikes in Syria expended fifty-nine Tomahawks in 2017 and an additional sixty-six in 2018. The Navy bought just 100 Tomahawks in 2018 and then zero Tomahawks in 2019—failing to offset the expenditure rate of the Syria strikes.

Firing off more weapons than America buys causes stockpiles to decline quickly. The same weapons reserve the nation would need should Beijing seek to use force to take Taiwan while the United States is supporting wars in two other regions.

Like most of the United States high-tech precision-guided munitions, the Tomahawk suffers from a recent history of inadequate and unstable procurement. In the last ten years, $2.8 billion has been spent on TLAM procurement by the Navy to procure just 1,234 missiles.

While this stock may seem impressive at first glance, it does not come close to matching what is needed for a global navy confronting enemies in too many places at once.

Considering the U.S. Navy has over 140 ships and submarines capable of launching Tomahawks, new missile buys are spread thinly across available fleets, with the last decade’s Tomahawk buys amounting to just 8.8 new missiles per ship.

Nor has the president’s budget done enough to rectify the Navy’s Tomahawk shortfalls. In the 2024 White House budget request, the Navy would buy zero new land-attack Tomahawks and instead opt to invest in the experimental modification of fifty standard land-attack Tomahawks into the Maritime Strike Tomahawk (MST) variant, designed to hit ships at sea.

While Navy officials have emphasized their effort to expand Tomahawk production, budget documents indicate that production and delivery rates of the missile are set to decline before they improve. Considerable effort and dollars in the White House budget skew towards modification and capability enhancements for existing Tomahawks, rather than the purchase of new missiles.

With a minimum sustainment rate of ninety Tomahawks per year required to keep production lines running, the Army and Marine Corps are barely sustaining production with their buys of experimental land-launched versions of the missile. Additionally, while the Navy is working on increasing the annual production of Tomahawks through sales to allies, it remains to be seen just how much additional production capacity this will create.

Even if the Navy wanted to buy more missiles, it’s not clear that industry could surge to meet demand. Fluctuating Tomahawk buys have led to unstable production rates and poor business planning for the industry and its suppliers. Uneven demand has materialized in production bottlenecks of key components like rocket motors, which make it difficult to surge production.

This is concerning given that each new Tomahawk has a two-year long lead time to build. Navy documents indicate that orders from last year are not expected to start delivery until January 2025, at a rate of just five missiles per month.

Victory in the next war will require a robust arsenal and deeper magazine depth of our fighting forces. During Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, US forces launched roughly 800 land-attack Tomahawks during the initial invasion. By today’s production rate, that would take us a decade to replenish. Fighting China would certainly require far more—and Beijing knows it.

With an inadequate supply of Tomahawks, the Navy’s land attack capability will overly rely on naval aviation, the presence of which will not be guaranteed within the ranges of China’s dense air defense network and sophisticated rocket force.

Though the Senate’s version of the pending national security supplemental does allocate $2.4 billion to replenish combat expenditures from operations in the Red Sea, a closer reading of the bill indicates that this topline does not go entirely to replenishing combat expenditure but instead the entire operation as a whole. The funding will thus be split between various accounts, in accordance with the Secretary of Defense’s recommendations, and may not adequately address this Tomahawk shortfall.

While an additional $133 million in the bill for cruise missile rocket motors is a welcome investment for relieving bottlenecks, Congress should also force the Navy to procure a steady quantity of the missile for years to come.

While the Senate’s supplemental may be a step in the right direction, it is also imperative for appropriators in Congress to recognize their pivotal role in sustaining our Navy’s strike capabilities. The Navy needs defense appropriations to kick-start key initiatives and lock in key munition buys.

Strikes against the Iran-backed Houthis and terrorists in the Red Sea are necessary, and the Tomahawk is the right tool for the job. But the Pentagon cannot allow these strikes to undermine the Navy’s readiness and capabilities in other theaters. Insufficient procurement will only lead to empty launch cells across our fleet and guarantee that the next war will not end on our terms.

About the Author

Mackenzie Eaglen is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where she works on defense strategy, defense budgets, and military readiness. She is also a regular guest lecturer at universities, a member of the board of advisers of the Alexander Hamilton Society, and a member of the steering committee of the Leadership Council for Women in National Security.

Main Image: U.S. Navy Flickr