Angela Merkel's German Problem

Merkel may well be the latest casualty of the European financial crisis.

German Federal Chancellor Angela Merkel does not just have a Greek problem. She also has a German one. Germans, as never before in the history of the Federal Republic, are in revolt. The latest bailout package, which includes expanding the European Financial Stability Facility—a longwinded official name for something more prosaic, namely, a rescue fund—is supposed to be comprised of trillions in aid. It's supposed to be a moment of shock and awe that shocks financial markets back into good health.

German Federal Chancellor Angela Merkel does not just have a Greek problem. She also has a German one. Germans, as never before in the history of the Federal Republic, are in revolt. The latest bailout package, which includes expanding the European Financial Stability Facility—a longwinded official name for something more prosaic, namely, a rescue fund—is supposed to be comprised of trillions in aid. It's supposed to be a moment of shock and awe that shocks financial markets back into good health.

But the European problem is as much political as it is financial. The truth is that Germany sought to bury its identity in Europe after World War II. How nice to be able to call yourself, not a German (bad, bad), but something else—a European. This was supposed to signify that Germans had long left behind the old Adam of German nationalism. No longer would Germany be the nation looking for its place in the sun. Instead, it would be the obedient, dutiful Zahlmeister—the paymaster—of a beneficent Europe.

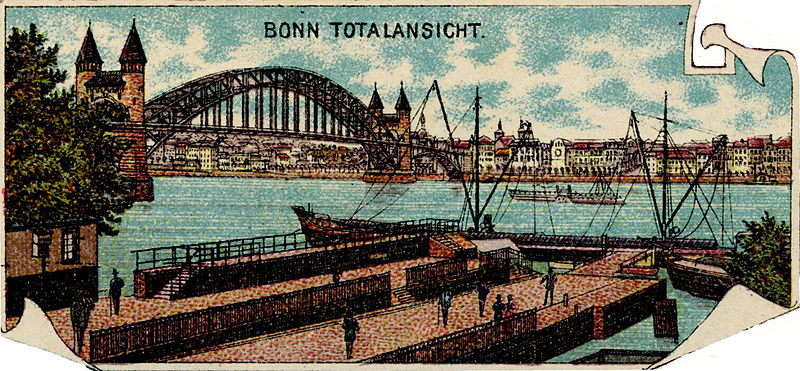

Then came the fall of the Berlin Wall. A lengthy debate ensued over whether the capital of Germany should be in Berlin or cozy little Bonn. The German parliament elected for the former. Germany needed a capital commensurate with its new size. It was the right choioce. But it also signaled that Germany was becoming something other than simply a small nation buried in the European Union. Eventually, it would have to begin to assert its own national interests.

Now Merkel is trying to split the difference. The woman from the East probably does not have the emotional attachment to the European Union that her precedessors such as Helmut Kohl did. Kohl looked West. Merkel had a different experience. She also looks to Russia as a business partner. But at the same time, Merkel does not want to abandon the Euro. She would like to save it, but without seeing Germany stuck with the tab.

Merkel's conundrum is that voters are fed up, engaging in what amounts to a populist rebellion. Merkel's coalition partner, the Free Demcoratic Party, has belatedly tried to jump on the populist bandwagon by raising questions about assisting Greece. But it has suffered a thumping at the polls. Too little, too late. Merkel's coalition is in jeopardy. She could end up in a new coalition with the Social Democrats. But her victory in a fresh campaign would by no means be certain.

Hence Merkel's indecisiveness on whether or not to offer Greece more funds. Parliament will likely approve more aid—but Merkel may only be able to pass it with the aid of the Social Democrats, exposing her own coalition as in shambles. Merkel has been a survivor. But she, too, could end up being one of the casualities of the European financial crisis.