Kim Jong-Un's Apology: Can It Spark a Diplomatic Breakthrough?

However unprecedented an apology may be, it will have little effect over the long-term if the two Koreas don’t take the next step. Kim’s statement is a small olive branch, but the opportunity will slip away if the United States doesn’t do its part to facilitate it.

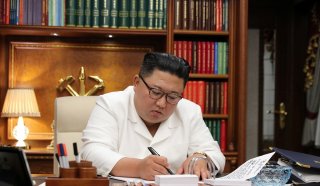

It’s not every day North Korea’s Kim Jong-un sends an apology letter. But this is exactly what happened this week after a South Korean official on the high seas was approached by a North Korean naval vessel and killed.

“I am deeply sorry that an unexpected and unfortunate thing has happened in our territorial waters that delivered a big disappointment to President Moon Jae-in and the people of the South,” Kim wrote to the South Korean government. The fact a statement of contrition was issued at all—under Kim Jong-un’s own name, no less—is a clear illustration of Pyongyang’s attempt to prevent the crisis from escalating.

However unprecedented an apology may be, it will have little effect over the long-term if the two Koreas don’t take the next step. Kim’s statement is a small olive branch, but the opportunity will slip away if the United States doesn’t do its part to facilitate it.

President Donald Trump’s North Korea policy has often been called unconventional. Trump calculated that if you want to get anything done with the North Koreans, you needed to reach out to the one person—Kim Jong-un—who is empowered to make the major decisions.

In terms of the strategy, however, Trump’s approach is practically identical to the presidents before him. To the surprise of no one, meeting directly with Kim won’t have much of an impact if Washington spends its time at the table pressing for the same maximalist demands. Trump thought striking a close personal relationship with Kim would persuade the North Korean leader over time to relinquish Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal. Unfortunately, Kim has proven himself to be just as protective of his country’s nuclear deterrent as his father before him. It’s not difficult to see why—surrounded by neighbors that are wealthier and more militarily capable than itself, the North Korean political leadership is living in a vastly disadvantageous geostrategic environment. At the moment, no diplomatic benefits, economic inducements, or security assurances Washington can offer are valuable enough for the Kim dynasty to trade away its ultimate security guarantee.

Yet just because the North Koreans aren’t willing to play ball on their nuclear weapons program doesn’t mean they aren’t open to a more productive relationship with the U.S. or South Korea. Indeed, there was a time in the not-so-distant past when North and South Korean soldiers were shaking hands and sharing cigarettes with each other as they demolished guard towers on both sides of the Demilitarized Zone. Notwithstanding the typical consensus in Washington, denuclearization is not a prerequisite for engaging in the time-consuming work of peace—or at least smooth, non-hostile working relations. Of course, this prognosis wouldn’t hold if North Korea was run by a bunch of crazies itching to use its nuclear weapons at the slightest sign of trouble. Fortunately, the Kim dynasty is quite rational in terms of knowing where the red-lines are—and needless to say, deploying nuclear warheads against the U.S. or its allies in a real-world situation is about as smart as skydiving without a parachute.

The chances of the U.S. achieving denuclearization in the short or medium term are less than minuscule. But the chances of achieving a general sense of stability on the Korean Peninsula are still quite realistic, even if communications between the North and South are largely cut and the inter-Korean liaison office that was meant to serve as a de facto embassy is now destroyed.

Can Pyongyang, Seoul, and Washington make progress in this regard? Yes, but it will require a dramatic sea-change from the U.S. in how it looks at the North Korea issue.

First and foremost, U.S. policymakers need to separate the peace track from the denuclearization track. As it stands, the two goals are intrinsically linked, which means Washington is allowing an unrealistic objective (a non-nuclear North Korea) to obstruct what is both possible and desirable (detente on the Korean Peninsula, hopefully leading to a full peace regime).

Second, the U.S. and North Korea should begin the process of diplomatic normalization by increasing the pace of exchanges between their diplomats and national security officials. The most efficient way to do this is through the creation of liaison offices, an idea the Trump administration considered shortly before Trump and Kim met for their second summit in Hanoi. This idea should be brought back into contention. Establishing more sustainable communication with the North is not a concession to Pyongyang, but rather a low-cost way to reduce risk and ensure any future miscalculations between the two are brought under control before they escalate into a crisis.

Third, Washington should provide its South Korean allies with the freedom to actually pursue its own North Korea policy. Currently, there is only so much Seoul can do to improve relations with its neighbor to the north without being stymied by the tangled web of U.S. and U.N. sanctions, which essentially prevent any business with Pyongyang unless authorized by the Security Council. Despite South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s grand plans for inter-Korean reconciliation—plans he expressed as recently as September 23 during his address to the U.N. General Assembly—his administration is virtually powerless to pursue any economic exchanges with Pyongyang with the exception of the small bartering of goods. The U.S. in effect holds a veto over South Korea’s policy towards the North, a degree of leverage that hinders the kind of inter-Korean cooperation that can form the foundation of lasting peace.

In the end, the U.S. possesses more than enough military power to live with a nuclear-armed North Korea. What it can’t afford is an environment where tension is considered normal along the most militarized border in the world.

Daniel R. DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities and a columnist for the Washington Examiner.