South Korea's Economic Policies Prepared It for the Coronavirus—North Korea's Did Not

While Pyongyang appropriates its citizens’ foreign currency, Seoul becomes a safe haven for foreign investors.

The coronavirus pandemic casts into sharp contrast the fortunes of North and South Korea, showing how differently they have evolved in the seven decades since the Korean War. Pyongyang’s inability to deal with the virus in any way other than to shut its borders and restrict domestic travel has sparked a huge shortfall in government revenue. The country has no access to external credit and its rudimentary banking system and capital markets are insufficient to allow it to access internal funds. Rather, it is struggling to fund its pre-crisis budget and public works program by appropriating the “idle” foreign currency holdings of its citizens. Meanwhile, Seoul’s timely and effective response to the virus that avoided lockdowns and blockades is held up as a worldwide example, burnishing South Korea’s status as a financial safe haven which allows it to affordably fund stimulus measures with government debt.

The pandemic forced Kim Jung-un to seal North Korea’s borders with China and Russia, depriving the country of more than 90% of its trade and tourism foreign exchange revenue. Loss of this revenue will likely make the financial effects of the virus much more devastating for North Korea than for any other country in Asia, if not the world, because of Pyongyang’s extremely high dependence on border trade in goods and services. While Pyongyang does not publish fiscal data and its sparse policy statements have little analytical content, South Korean news reports say the government expects a huge, 60% revenue shortfall. North Korea’s public finances are under the most intense pressure since the 1990s, when famine brought about by drought, the loss of Soviet support, and mismanagement caused 600,000 to 1 million deaths out of a pre-famine population of roughly 22 million.

To fill the huge revenue shortfall, North Korea is reportedly issuing bonds, or at least some type of I.O.U., for the first time in seventeen years since “People’s Bonds” were issued to citizens to mop up local currency liquidity and contain inflation. The aim of the new debt issuance is to collect as much foreign currency as possible from state factories and the country’s budding donju entrepreneur class, which accumulated foreign currency from trade with China. Such funds were not deposited in the Chosun Central Bank nor in the Foreign Trade Bank and, being outside the control of the state, are considered “idle” by authorities. As in 2013, North Korea apparently will not resort to inflationary budget and state-enterprise financing through its central bank.

The urgency of this task is shown by reports that Kim Jong-un’s sister, Kim Yo-jong, is overseeing a review of the bond program. But a South Korean report indicates that demand is weak, with only 8% of the targeted placement achieved so far, even though purchase of the bonds is compulsory. Non-compliance has dire consequences, as illustrated by the reported execution of a coal mine owner in suburban Pyongyang who resisted purchasing his state-directed allocation. However, such coercion has not gone well for the government in the past. Its 2009 currency re-denomination achieved its goal of confiscating the local currency savings of citizens, but precipitated unprecedented social unrest.

Meanwhile, thanks to its open financial system and in part to its effective response to the virus, global investors are buying South Korea treasury bonds, in spite of the historic sell-off in other emerging market debt. Foreign bond funds purchased a net $22 billion of South Korean treasury bonds in the first four months of 2020, according to Bloomberg. At the same time, foreign bond funds withdrew $41 billion from six of the other largest developing nations, namely India, Indonesia, Thailand, Mexico, Turkey, and South Africa. The net inflow is helping South Korea finance, at an affordable interest rate cost, an aggressive stimulus program to counter the drop in demand from the pandemic. Why is this?

Fundamentally, South Korea has the ability to resist or respond effectively to shocks, even the corona-virus pandemic, owing to its macroeconomic, institutional, and fiscal strengths. These virtues are reflected in its double-A credit ratings from all three major international agencies: Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch. Korea’s fiscal strength is also reflected in the U.S. Federal Reserve’s decision to extend a $60 billion foreign exchange swap line with the Bank of Korea, ensuring adequate foreign currency liquidity to the system. The Fed would only expose its balance sheet if it judged cross-border risk to be small.

Seoul’s ability to contain the spread of the pandemic has likely played a role. South Korea’s high degree of vigilance, transparency, and public health capacities proved highly effective in minimizing mortality. It avoided shutting its borders and did not resort to draconian lockdowns. Its medical system handled hospitalizations competently and with spare capacity, unlike the bungled responses elsewhere, particularly in New York City.

The efficacy of South Korea’s pandemic response has engendered a high degree of public trust and contained the damage to the country’s economy to a much greater degree than in the U.S. and the hardest hit countries in Europe. In its latest release, Statistics Korea marks the country’s seasonally adjusted unemployment at 4.5% in May. Although a ten year high, the labor market in South Korea compares favorably to the United States, where the unemployment rate was 13.3% in May, the highest rate in more than 70 years. Although South Korea is dependent on exports, it has not suffered as much economic devastation as other countries and therefore is poised to bounce back relatively more strongly from the effects of the pandemic—enhancing the country’s credit quality—as long as the global economy also heals.

Meanwhile, North Korea’s complete lack of transparency makes it ineligible for the benefits of International Monetary Fund (IMF) membership and its nuclear ambitions have brought sanctions. It has no access to the sizable pandemic emergency lending facilities being provided by the IMF and World Bank to emerging market and poor, highly indebted countries. Lacking creditworthiness, Pyongyang also can’t access global capital markets. Its only recourse is to coercively raise domestic funds. A virtually nonexistent financial system is otherwise incapable of raising foreign currency savings from the new class of gray market donju merchants and entrepreneurs.

The coronavirus shock has pushed North Korea’s public finances to the edge, with no fiscal buffers or access to credit to cushion the blow. Even the Cuban government, the only other notable non-member of the IMF, can obtain non-inflationary financing for its deficits from state-owned domestic commercial banks and has had, at times, access to external financing. Because North Korea distrusts empowering a private sector, it does not seek to develop its financial sector, and eschews reform and economic opening. As a consequence, it lives on the edge financially and at the brink geopolitically. Who suffers? Not so much the elites in Pyongyang, but the 20 million ordinary citizens who have to fend for themselves.

The Korean Workers’ Party newspaper stated in the April 2020 budget announcement that, “provinces, cities and counties would cover expenditure with their own revenue and contribute lots of funds to the centrally-run budget,” in fact, 25.7% of the total budget. This predatory fiscal arrangement is another indication of North Korea’s financial stress under sanctions and the pandemic. Choices matter, and Kim Jong-un’s decision to stubbornly stick to juchae, the self-reliance policy the young leader inherited from his father and grandfather, is having dire consequences.

A quote from economic development scholars illustrates the divergent paths of the two Koreas since World War II and the end of Japanese colonization. “There are no money or capital markets in the accepted sense of the terms and no really adequate facilities for mobilizing such savings as are currently made and for channeling them into productive investments…the government has…only recently announced its first pending issue of bonds, which are to be sold to the public and banking institutions on a more or less compulsory basis.”

Applicable to North Korea’s current predicament and actions, those words were actually used to describe South Korea’s financing conditions in 1950, as a new democratically elected government struggled to rebuild a collapsed fiscal and financial system. South Korea has since come a long way, in stark contrast to the North. Financial market development is one prism through which to view relative development on the Korean Peninsula. While North Korea coerces funds from its state factories and donju, South Korean treasury bonds are considered a safe haven for investors in an uncertain time.

Who could have imagined where history has taken the two Koreas, looking back 70 years ago when North Korean armies crossed the 38th parallel on June 25, 1950 and overran Seoul in three days? The Armistice signed on 27 July 1953 suggested a draw in the contest between the two Koreas, but the 2020 bond market unequivocally signals South Korea the winner.

Thomas Byrne is the president and CEO of the Korea Society in New York City and an adjunct professor at Columbia and Georgetown Universities. He was Moody’s Asia-Pacific and Middle-East Sovereign Risk Group manager.

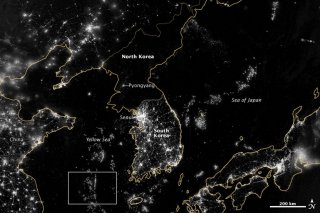

Image: NASA