The Danger of Process-Free Foreign Policy

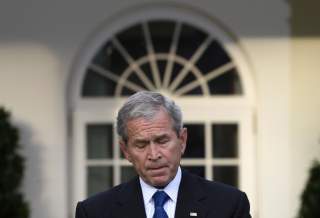

Trump's handling of Iran recalls one of the most extraordinary aspects of the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq: there was no policy process leading to the decision to launch that war.

The disturbing parallels between Donald Trump’s policy toward Iran and the run-up to the disastrous U.S. offensive war against Iraq keep piling up. There is a drumbeat of belligerent rhetoric, with no limit to what the targeted country gets accused of doing. There is a highly selective, tendentious public use of intelligence, including presentations either to the United Nations or from an ambassador to the United Nations. There are even some of the same people—including John Bolton—who still says the Iraq War was a good thing, who has made no secret of welcoming a war with Iran, and who today is Trump’s National Security Advisor.

Mark Landler's reporting in The New York Times about the run-up to Trump’s reneging on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the agreement that restricts Iran’s nuclear program, points to a less obvious but no less important parallel. Bolton did not convene any National Security Council meeting to discuss the likely consequences of violating the JCPOA and whether doing so would be a good idea. This recalls one of the most extraordinary aspects of the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq: there was no policy process leading to the decision to launch that war. There was no options paper, no debate in the Situation Room and no other opportunity for members of the administration to discuss whether starting that war was a good idea. The question simply wasn’t on any meeting’s agenda.

Of course, chaos in Donald Trump’s White House and the impulsive and personal nature of much of his decision-making are hardly news. But the effort to wreck the JCPOA has not been a passing impulse. Trump has long ranted about the accord, and there was ample opportunity to have a sober in-house discussion of the subject if he had wanted one. As with the Iraq War, the creation and timing of a crisis were all the White House’s own doing.

Much commentary about the Trump administration’s policies has focused on who’s in and who’s out in senior positions. The unusually high personnel turbulence in this administration has naturally made that a major topic. But process can matter as much as personalities. Consider the situation of Secretary of Defense James Mattis, who is being looked to more than ever as the remaining adult in the room and who, despite his own emotional hang-ups regarding Iran, reportedly favored adhering to the JCPOA. Mattis’s problem was not just that he may have been outnumbered on that issue among those who somehow got the president’s ear. The problem was that there was no forum in which he and others in the administration could formally and explicitly raise and discuss all the reasons that trashing the JCPOA would be a mistake.

Most major foreign policy decisions in most administrations do have a full policy process, which entails debate and discussion at several levels and examines the pros and cons of all relevant policy options. Cumbersome though it may be at times, such a process is the best way to confront myths and misadventure with facts and insight. Not all bad policy impulses get stopped, but there is much more chance of stopping them with a thorough policy process than without one.

The facts and insight often are readily available within the executive branch. Consider some of the insights relevant to the Iraq War that were available within the Bush administration. There was, for example, Army chief of staff Gen. Eric Shinseki, who before the war estimated that several hundred thousand troops would be needed for success in Iraq, a number far higher than what promoters of the war were advertising. There was economic policy advisor Lawrence Lindsay, who estimated the cost of the coming war would be $100–200 billion—which turned out to be a gross underestimate, but again was higher than what the war promoters wanted people to believe. And there was the U.S. intelligence community, which, as was revealed only later, foresaw before the war most of the costly and bloody mess in Iraq that would ensue once Saddam Hussein was toppled. Shinseki and Lindsay were purged, and the intelligence community was ignored. If there instead had been a policy process in which they and others could have weighed in on the question of whether to launch the invasion, the neocon mythology about a wonderful war would have had a harder time withstanding scrutiny.

The danger that Bolton represents goes beyond his warmongering views and extends to his control of policy processes, and with it his ability to curtail or prevent such processes. If government is working properly, one of the most important functions of the National Security Advisor is to ensure that major foreign policy issues are thoroughly considered before they reach the president for decision, and that the president is provided in an orderly way with all relevant options and insights. Not performing this function regarding Iraq was probably the biggest failure of Condoleezza Rice when she was in the job, before she went on to have a better performance as secretary of state. The nation appears to be in for more misadventures in foreign relations not only because of the impulsiveness and chaotic thinking of the man at the top but also because the policy-making machinery that would otherwise check such tendencies is not being allowed to operate.

The disturbing parallels between Donald Trump’s policy toward Iran and the run-up to the disastrous U.S. offensive war against Iraq keep piling up. There is a drumbeat of belligerent rhetoric, with no limit to what the targeted country gets accused of doing. There is a highly selective, tendentious public use of intelligence, including presentations either to the United Nations or from an ambassador to the United Nations. There are even some of the same people—including John Bolton—who still says the Iraq War was a good thing, who has made no secret of welcoming a war with Iran, and who today is Trump’s National Security Advisor.

Mark Landler's reporting in The New York Times about the run-up to Trump’s reneging on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the agreement that restricts Iran’s nuclear program, points to a less obvious but no less important parallel. Bolton did not convene any National Security Council meeting to discuss the likely consequences of violating the JCPOA and whether doing so would be a good idea. This recalls one of the most extraordinary aspects of the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq: there was no policy process leading to the decision to launch that war. There was no options paper, no debate in the Situation Room and no other opportunity for members of the administration to discuss whether starting that war was a good idea. The question simply wasn’t on any meeting’s agenda.

Of course, chaos in Donald Trump’s White House and the impulsive and personal nature of much of his decision-making are hardly news. But the effort to wreck the JCPOA has not been a passing impulse. Trump has long ranted about the accord, and there was ample opportunity to have a sober in-house discussion of the subject if he had wanted one. As with the Iraq War, the creation and timing of a crisis were all the White House’s own doing.

Much commentary about the Trump administration’s policies has focused on who’s in and who’s out in senior positions. The unusually high personnel turbulence in this administration has naturally made that a major topic. But process can matter as much as personalities. Consider the situation of Secretary of Defense James Mattis, who is being looked to more than ever as the remaining adult in the room and who, despite his own emotional hang-ups regarding Iran, reportedly favored adhering to the JCPOA. Mattis’s problem was not just that he may have been outnumbered on that issue among those who somehow got the president’s ear. The problem was that there was no forum in which he and others in the administration could formally and explicitly raise and discuss all the reasons that trashing the JCPOA would be a mistake.

Most major foreign policy decisions in most administrations do have a full policy process, which entails debate and discussion at several levels and examines the pros and cons of all relevant policy options. Cumbersome though it may be at times, such a process is the best way to confront myths and misadventure with facts and insight. Not all bad policy impulses get stopped, but there is much more chance of stopping them with a thorough policy process than without one.

The facts and insight often are readily available within the executive branch. Consider some of the insights relevant to the Iraq War that were available within the Bush administration. There was, for example, Army chief of staff Gen. Eric Shinseki, who before the war estimated that several hundred thousand troops would be needed for success in Iraq, a number far higher than what promoters of the war were advertising. There was economic policy advisor Lawrence Lindsay, who estimated the cost of the coming war would be $100–200 billion—which turned out to be a gross underestimate, but again was higher than what the war promoters wanted people to believe. And there was the U.S. intelligence community, which, as was revealed only later, foresaw before the war most of the costly and bloody mess in Iraq that would ensue once Saddam Hussein was toppled. Shinseki and Lindsay were purged, and the intelligence community was ignored. If there instead had been a policy process in which they and others could have weighed in on the question of whether to launch the invasion, the neocon mythology about a wonderful war would have had a harder time withstanding scrutiny.

The danger that Bolton represents goes beyond his warmongering views and extends to his control of policy processes, and with it his ability to curtail or prevent such processes. If government is working properly, one of the most important functions of the National Security Advisor is to ensure that major foreign policy issues are thoroughly considered before they reach the president for decision, and that the president is provided in an orderly way with all relevant options and insights. Not performing this function regarding Iraq was probably the biggest failure of Condoleezza Rice when she was in the job, before she went on to have a better performance as secretary of state. The nation appears to be in for more misadventures in foreign relations not only because of the impulsiveness and chaotic thinking of the man at the top but also because the policy-making machinery that would otherwise check such tendencies is not being allowed to operate.