Economic Stagnation is at the Heart of the Belarus Protests

Author: After watching more than 100 interviews with ordinary Belarusians on non-state TV channels over the course of the presidential campaign and closely following how the protest is unfolding, it is clear to me that a decade of economic stagnation is at the heart of the ongoing protests over Lukashenko’s re-election and that people have no hope that he will fix the problem.

Mass protests in Belarus continue to contest the result of the country’s recent election, which gave a landslide victory to longtime leader Alexander Lukashenko. It is not the first time in his six terms as president that people have taken to the streets. But this time the protests are driven by a number of economic factors that were not present in 2001, 2006 and 2010.

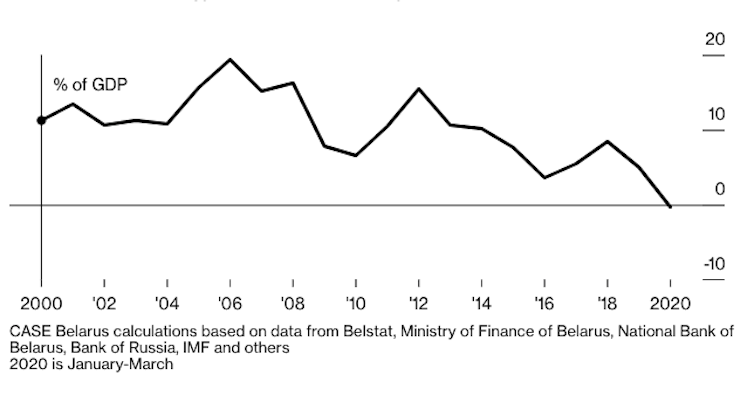

Deep economic crisis caused by the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and worsened by the Russian financial crisis of 1998 was followed by a decade of economic growth. But the decade following the 2008 financial crisis has brought back memories of the 1990s.

By 2011 Belarus was in a full economic crisis, which triggered mass protests. A currency crisis in 2014 and the “tax on social parasites” in 2015 led to nationwide protests in 2017.

After watching more than 100 interviews with ordinary Belarusians on non-state TV channels over the course of the presidential campaign and closely following how the protest is unfolding, it is clear to me that a decade of economic stagnation is at the heart of the ongoing protests over Lukashenko’s re-election and that people have no hope that he will fix the problem.

Unsustainable economic system

Economic growth in the 2000s was mainly driven by favourable external factors rather than Lukashenko’s “market socialism” which many economists believe is no longer sustainable. While neighbouring Poland and most of the former USSR republics, including the Baltic States, started to transition to a market economy, Lukashenko was unenthusiastic about this kind of reform.

A major reason has been the country’s close ties to Russia, as a long-term provider of cheap crude oil and gas and other subsidies in exchange for Belarus’s integration in a “union state” with its neighbour. But Lukashenko has failed to use this advantage to find new sources of income.

More recently, ties between Belarus and its biggest trading partner have become strained. Lukashenko recently fell out with Vladimir Putin and Russia has been playing hard ball with its subsidies. This has coincided with a decrease in GDP growth from a pre-2008 crisis average of 8% to post-crisis 2%.

Other poor decisions by Lukashenko’s government in recent years include the move to increase the country’s average salary to US$500 a month. This was a pre-2010 election promise that was achieved by printing money. It contributed to a currency crisis and the Belarusian rouble devalued by more than 60% in 2011.

Inflation then hit 109% and the average wage decreased by 38% from US$530 to US$330. Further declines in its currency have followed.

In 2015, Lukashenko made another unpopular decision to tax people for being unemployed. It was an attempt to crack down on tax evasion and people working in informal employment. But when the deadline for paying this tax approached in 2017, only 11.5% of 470,000 people had paid.

So the economy was struggling well before coronavirus hit. The World Bank predicts a severe shock to the Belarus economy from COVID-19. But Lukashenko’s response to the pandemic was to advise people to go to saunas and drink vodka. It did not go down well.

What the future holds

Belarus was one of the most prosperous parts of the post-war Soviet Union and, after its collapse, it was the second most developed independent state in terms of GDP per capita. It is characterised by highly educated people and a well-developed industrial and agricultural base. But the failing economy is pushing more people to emigrate, depriving the country of many of its main assets.

The success of Hi-Tech Park, a technology and innovation hub developed by Valery Tsepkalo, a would-be presidential candidate who was barred from standing in the recent election, is proof of how economic reforms can realise the potential of human capital in this country. Home to internationally successful apps such as Flo and Viber, along with popular video games, including World of Tanks, the park has become one of the largest IT outsourcing providers in Europe and contributed significantly to the country’s GDP.

But after a decade of the economy stagnating and further contracting due to coronavirus, people are fed up. This is why they are protesting.

Even workers in large state-owned enterprises, traditionally the pillar of Lukashenko’s economic model, have heeded the opposition’s calls to strike. They are making the financial sacrifice in the short term, hoping to achieve a better economy in the long run. They are joined by professionals across industries, including journalists and state officials.

Meanwhile, Lukashenko is running out of options. With people queuing at currency exchange points and struggling to withdraw money from their accounts, the country is on the cusp of another currency crisis.

To prevent this, Lukashenko needs money. It will be challenging for him to obtain funds from the IMF, as he failed to implement the agreed economic reforms that came with borrowing in 2011. Loans from Russia or China will not lead to reforms but more dependence.

If the current protest doesn’t succeed, anger at the country’s deep-seated economic issues will only grow even greater. It leaves Lukashenko’s government with little room for manoeuvre.

![]()

Yerzhan Tokbolat, Lecturer in Finance, Queen's University Belfast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters