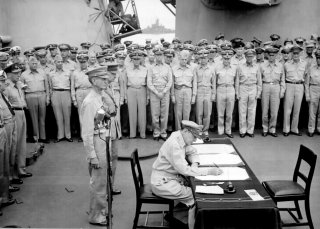

12,000 U.S. Troops Once Surrendered to the Japanese Military

In a forgotten moment of history, over ten thousand U.S. soldiers publicly surrendered to Japanese forces in the Philippines.

Here's What You Need to Remember: Under the cameras of Japanese photographers and the contemptuous glare of Japanese officers, Gen. Jonathan Wainwright surrendered the last of the U.S. garrison in the Philippines.

“Tell Joe, wherever he is, to give ’em hell for us,” said the radio signal. “My love to you all. God bless you and keep you. Sign my name, and tell mother how you heard from me. Stand by.”

And then there was silence.

On the morning of May 6, 1942, U.S. Army Sgt. Irving Strobing sent the last message—to America, his family and his brother Joe—from the fortress of Corregidor, an island at the mouth of Manila Bay. A few hours later, under the cameras of Japanese photographers and the contemptuous glare of Japanese officers, Gen. Jonathan Wainwright surrendered the last of the U.S. garrison in the Philippines.

From Corregidor’s tunnels emerged eleven thousand starving, wounded and exhausted American and Filipino prisoners, including several American nurses. They swelled the ranks of the defenders of the Bataan peninsula, who had surrendered on April 9. By early May 1942, the Japanese had captured seventy-six thousand American and Filipino soldiers in the largest surrender in U.S. history.

On the seventy-fifth anniversary of the fall of Corregidor, the question still remains: what went wrong?

The answer is pretty much everything. The problems began with an impossible strategic situation. Manila is only two thousand miles from Japan, but five thousand miles from Pearl Harbor. By the 1930s, it was obvious that in the case of war, the Philippines would be isolated by the Japanese Navy, bereft of reinforcements and resupply. War Plan Orange called for the U.S. Navy to conduct a naval cavalry charge across the Pacific to relieve the garrison. At best, this would be chancy; at worst, Japanese aircraft and subs would whittle down the U.S. fleet; and in reality, the Pearl Harbor disaster left no fleet to come to the rescue.

None of which was Philippines commander Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s fault, but much else was. Under his watch, essential defense preparations were left undone (exacerbated by tight prewar budgets). By December 7, 1941, U.S. Army and mobilized Filipino troop strength had soared from thirty-one thousand to 130,000 troops. But the Filipinos in particular were poorly trained and armed, and the defenders were scattered across the islands of the Philippines. The Far East Air Force had perhaps three hundred aircraft, but that included only thirty-five B-17s and another hundred modern P-40 fighters, with the rest obsolete models. The Asiatic Fleet based in Manila had only a handful of ships, some submarines, plus the Fourth Marine Regiment.

News of Pearl Harbor awakened MacArthur at 3 a.m. December 8. The aircraft at Clark Field should have been dispersed and then launched to bomb Japanese airfields on Taiwan. With bad weather delaying the Japanese strike for nine hours, the Americans might have caught Japanese planes on the ground—if MacArthur had authorized it. Instead the Japanese caught the American air fleet on the ground and decimated it, thus depriving the defenders of their only chance to disrupt the impending amphibious landing.

Later on December, Japanese troops landed on northern Luzon, unmolested for a handful of U.S. aircraft (which still managed to sink or damage several ships). But this was only a sucker punch before the main landing: on December 22, the Japanese Fourteenth Army landed in Lingayen Gulf, in the center of Luzon and close to Manila and Clark Field. This was followed by a smaller landing in southern Luzon.

Outflanked and outmaneuvered, MacArthur ordered Plan Orange, a delaying action by rearguards while the bulk of his forces moved into the defenses of the Bataan Peninsula near Manila. Covered by detachments of U.S. and Filipino troops, including some M3 Stuart light tanks, eighty thousand troops and twenty thousand civilians made it into Bataan. Unfortunately, Plan Orange called for sufficient supplies for only forty-three thousand troops to dig in at Bataan.

Nonetheless, the Bataan troops fought bravely and inflicted heavy losses. But unless the U.S. Navy could instantly resurrect the sunken battleships at Pearl Harbor, the Philippines were doomed. Backed by heavy air support, the Japanese eventually broke through the lines of starving and ill defenders. Most eventually surrendered, but a few made it to Corregidor, defended by a motley assortment of Army, Marine and Filipino troops. Lacking food and medicine, they too were bombed and shelled until they surrendered May 6.

And MacArthur? The Bataan troops composed a song about him to the tune of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”:

Dugout Doug MacArthur lies ashaking on the Rock

Safe from all the bombers and from any sudden shock

Dugout Doug is eating of the best food on Bataan

And his troops go starving on.

Dugout Doug’s not timid, he’s just cautious, not afraid

He’s protecting carefully the stars that Franklin made

Four-star generals are rare as good food on Bataan

And his troops go starving on.

Dugout Doug is ready in his Kris Craft for the flee

Over bounding billows and the wildly raging sea

For the Japs are pounding on the gates of Old Bataan

And his troops go starving on . . .

But MacArthur was busy with other things. He was awarded $500,000 by Philippine president Manuel Quezon for his prewar service, and his staff also got money (Eisenhower was offered money, but turned it down). To be fair, he was ordered by President Roosevelt to fly himself and his family aboard a B-17 to Australia. Following orders, to be sure, but his troops weren’t so lucky. Between the cruelty of the Bataan Death March, and for the survivors the brutality of Japanese prison camps, 40 percent of the Americans never made it home.

“I will return,” MacArthur vowed. And he did—on October 20, 1944, and in the presence of photographers.

Michael Peck is a contributing writer for the National Interest. He can be found on Twitter and Facebook. This article first appeared in 2017 and was republished due to reader demand.

Image: Wikipedia