A Coronavirus Must: How to Overcome Needle-Phobia

The widespread fear of needles is a public health problem, particularly in the time of COVID-19.

As progress continues toward finding a vaccine that prevents COVID-19, millions of Americans are frightened at even the notion of getting a shot: Studies suggest 63% of young adults – those born in 2000 or later – fear needles.

As a physician trained in pediatrics, I think we found the answer for the huge rise in needle phobia. Now – and even more critical: What might alleviate needle pain and fear?

A landmark 1995 study on needle phobia reported that 10% of adults and 25% of children were afraid of needles. The study also noted what typically caused their fear: a “needle event” around five years of age.

In 2010, our team conducted a study of vaccination pain in preteens. Of the 120 children screened, 114 said they had needle anxiety. This really surprised us. As with the earlier study, we thought perhaps 25% would be afraid; instead, it was 95%. (Incidentally, some of the parents were annoyed – not a few called their children out for being “wimps.”)

Why there’s more needle phobia

We wanted to understand what was creating this new anxiety. So we looked at the vaccination records of the group since birth. Maybe then we could find patterns that caused this abrupt rise in fear.

Turned out it was the needles.

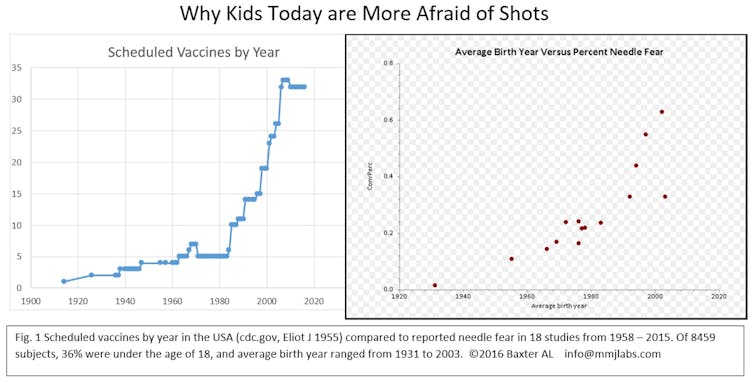

Over the past 40 years, we have added 30 injections to a child’s vaccine schedule. This is a good thing: Today in the U.S., kids almost never die from a childhood infectious disease. But needle fear has blossomed.

The number of infant vaccines were fine. But we found that half of kids who got all their preschool boosters on one day – that’s four or five injections at once – were in the highest quartile of fear five years later. Worth noting: Over the next three years, this group was two-and-a-half times less likely to get the HPV vaccine.

But none of the kids who got only a single shot each visit over the full four- to six-year window was fearful. Perhaps they became resilient, capable of coping with one quick poke. Maybe five injections per visit is too much, particularly when you’re old enough to remember them.

Potential solutions

Experts in the field – like Dr. Anna Taddio of the University of Toronto – realized needle fear could impact vaccination rates. She and other Canadian scientists created guidelines to reduce vaccination pain. Issued in 2015, those guidelines suggested that interventions, occurring while preparing for and receiving the shot, would help.

Interventions can mean distractions. For young children, fear might be reduced by letting them blow their breath on a toy pinwheel. For an older child, it might be through watching videos or listening to music. For pain, topical anesthetics help numb the skin. So does numbing the muscle with “Buzzy,” the vibrating cold device we tested in preteens. Pain is reduced when placed on the shot area for a minute, then moved near the area while the injection takes place. Two meta-analyses showed Buzzy provided significant pain and fear relief – a 40% to 74% decrease for children, and a better experience for adults when receiving an flu shot.

In addition to Buzzy: Cold spray, topical anesthetics and Shotblocker – a horseshoe-shaped device placed near the area of the shot – have been studied for adult injections. Compared to no intervention, they helped reduce pain.

And in studies looking at blood donation, reducing anxiety and pain can lead to lower rates of the “passing out” feelings in adults. Using vibration combined with cold can also help adults who are fearful.

New guidelines could come out later this year. This too will be helpful; our knowledge of vaccine pain has greatly increased over the past five years. Many of the 2015 recommendations were speculative and extrapolated from studies of IV insertions, which do not directly correlate to pain interventions for shots. In addition, many studies evaluating distractions from blowing bubbles to wearing virtual reality goggles are from lab draws. Reliable data on immunizations is relatively scant.

Use multiple distractions, go in with a plan

Yet all the suggested interventions have a commonality. They address pain, fear and the frightening memories of past events by changing the patient’s focus during a procedure.

A systematic review for vaccine pain concluded that interventions should have cold and vibration, plus distraction elements – for instance, using Buzzy as the patient watches a video or listens to music. The patient should choose the activity, and then remain engaged as the shot is prepared and administered.

If you’re facing a needle – a vaccination, lab draw or blood donation – the best strategy is to have a plan beforehand. Discuss the procedure with the clinician; bring a friend along. Have a game you can play while it’s all happening – that way, the brain is too busy to be afraid, and pain perception goes down. Any smartphone app involving touch and skill is a great place to start. Maybe it’s time to play Pokemon Go again.

A physical intervention during the procedure – pointing, touching, coughing – can help. Or combine rote performance and visual identification. During the poke, look at something on the wall with writing on it; focus on one sentence and count the number of letters with holes in them (for example, there are two in “holes”). This engages the part of the brain responsible for analyzing risk.

Needle phobia is a direct threat to public health. Those who are afraid of shots may not get them. With COVID-19 upon us, addressing needle fear becomes more than making a doctor’s visit more pleasant. Now, it’s truly a lifesaving endeavor.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

![]()

Amy Baxter, Clinical Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, Augusta University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters