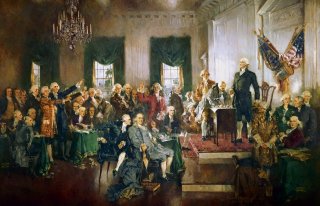

The Founding Fathers Would Want Us to Get the COVID-19 Vaccine

For all their failures and divisions, they all supported inoculation or vaccination. They did so because they embraced the basic arguments of the Enlightenment: people were not sentenced to the shadows and sorrows of the past, but rather made to live, to learn and ultimately to lift each other out of darkness and despair.

With the United States Capitol overrun by Trump’s deplorables, it was easy to miss the other calamity that hit America last week: the pace of COVID-19 deaths hit a frightful new high. In Los Angeles County, a victim now dies every six minutes.

The only way out of this carnage is rapid vaccination on a vast scale. Unfortunately, many Americans see vaccination as another threat to their personal liberty, another overreach by a distant yet hostile government.

They can feel that way. But they can’t say that the Founding Fathers would be on their side in this regard, because as men of the Enlightenment, the Founders were pro-vaccination.

Washington inoculates the troops

In the summer of 1775, George Washington took charge of the newly formed Continental Army. Setting out to liberate Boston from British occupation, he learned that smallpox — a highly contagious disease that killed about 25 per cent of victims and permanently disfigured many survivors — had broken out in that city.

Washington was preternaturally brave, but this news terrified him.

As a young man, he had nearly died of smallpox while visiting the Caribbean island of Barbados. His bout with the “speckled monster” left him pockmarked and possibly infertile. Most British soldiers were also immune to smallpox due to prior exposure, but most Americans had no such protection.

“If we escape the smallpox,” Washington told Congress that December, “it will be miraculous.”

A miraculous — but dangerous — remedy already existed. This was inoculation, the forerunner to vaccination. Long practised in West Africa and the Ottoman Empire, it meant rubbing a small amount of pus from a smallpox victim’s rash into the shoulder of a healthy person. About 95 per cent of the time, the result was a mild case and then immunity. But inoculation patients sometimes came down with the full-blown disease, and for a week or two they were highly contagious.

No wonder that many doctors and pastors condemned the practice as a violation of God’s will, or that furious crowds sometimes sacked and burned inoculation hospitals.

In 1776, however, Washington learned that a massive outbreak had decimated patriot forces in Québec and that the fear of smallpox kept new recruits from enlisting in the Continental ranks. John Adams, one of the patriot leaders of Massachusetts, called smallpox “10 times more terrible” than any human foe.

And so, in early 1777, Washington ordered all Continental soldiers to undergo inoculation, followed by a period of strict isolation. Within a year, smallpox had all but disappeared from his camp, saving the army and probably the Revolution.

The General trusted that even the “most rigid opposers” of inoculation would change their minds in the face of its “amazing” success.

Jefferson versus smallpox

Twenty years later, as the new United States struggled to survive in what remained a British-dominated world, the English physician Edward Jenner showed that vaccinia, which caused a harmless case of cowpox, also protected people against smallpox (hence, vaccination).

Even though his method was far safer than inoculation, many accused Jenner of treating people like livestock; in 1802, one cartoonist imagined cow parts growing out of the arms and faces of the vaccinated.

But Jenner found an unusual ally in the man who succeeded Washington and Adams as U.S. President: Thomas Jefferson.

More than any other Founder, Jefferson feared and despised British power. This is what made him radical: He dreamed of a world beyond the shadows cast by Royal Navy vessels and mechanized factories. He also celebrated scientific progress in general and medical advances in particular, once helping to draft a new, pro-inoculation law in Virginia in 1777.

And so Jefferson, the anti-British President, wrote to Edward Jenner in 1806, thanking the doctor on behalf of “the whole human family.” Jefferson also boasted that he was “among the early converts” to the technique. (Jefferson didn’t mention that he had tested the new technique on the enslaved members of his “family.”)

Against an enemy like smallpox, Jefferson believed, international conflicts were foolish. All nations were allies.

Madison and public health

Jefferson’s successor as president, James Madison, was a true believer in the limited powers that the U.S. Constitution — of which he was a principal author — granted the president, even in times of war.

Of course, the constitution did not specify a public health role for the federal government, either. In the early months of the war, however, Congress passed a bill to create a National Vaccine Institute, which would send vaccinia free of charge across the vast new country.

As the physician in charge of the institute argued, “every citizen should have the right secured to him of a free access” to this lifesaving material.

For Madison, this was not a constitutional issue but rather a common sense measure on behalf of what the constitution called the “general welfare,” a good deed that no good government could fail to do.

Foundations of public health

Washington was more of a soldier than a philanthropist. Jefferson was a racist philosophe whose dreams for white Americans were nightmares for all the others. Madison was better at designing governments than running one. They argued constantly about the proper role of government, the optimal pace of progress and the inherent tension between liberty and equality.

For all their failures and divisions, however, they all supported inoculation or vaccination. They did so because they embraced the basic arguments of the Enlightenment: people were not sentenced to the shadows and sorrows of the past, but rather made to live, to learn and ultimately to lift each other out of darkness and despair.

![]()

J.M. Opal, Associate Professor of History and Chair, History and Classical Studies, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters