The Future: How Campaigns Are Turning to the Internet During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Candidates now focus on three areas: social media, campaign-specific mobile apps, and paid advertising on social media.

This feels like it could be the most revolutionary moment in U.S. campaign history: Candidates are robbed of the typical ways for connecting with supporters and changing the hearts and minds of the voting public.

The coronavirus has ground the presidential campaigns of Joe Biden and Donald Trump to a near halt. Public rallies aren’t happening, and to follow social distancing guidelines, many of the campaigns’ local offices have stopped bringing in volunteers for phone banking or knocking on doors in local neighborhoods.

I have studied presidential campaigning since the 1996 election. In my book, “Presidential Campaigning in the Internet Age,” I document the ways that campaigns have evolved their campaign tactics to incorporate digital media.

For many years, political operatives have been perfecting their use of the internet’s vast array of social media platforms, websites and digital tools. They’ve identified effective strategies of digital communication with supporters and the press.

Now that traditional in-person campaigning has been severely limited, I believe campaigns will lean heavily on that digital experience, focusing in three areas: social media, campaign-specific mobile apps and paid advertising on social media.

An initial slowdown

In general, political campaigns group voters into three categories: supporters, opponents and a group in the middle, sometimes called “persuadables,” who don’t have a strong connection to a political party or who aren’t that into politics. The members of this third group could be persuaded to vote for the candidate on Election Day.

The key function of a campaign is to identify supporters and mobilize them to be the workhorses for the cause: give money, volunteer, promote the candidate and – of course – vote. Campaigns also need to find and communicate to the persuadables, in hopes of getting their backing. And campaigns need to identify those who oppose their candidates, so they don’t waste time and money getting them to vote, which would only help the other side.

Regrouping before the conventions

There are natural slowdowns and lulls in the campaign season, including when the presumptive nominees are settled on, but before the party conventions make the nominations official – like now.

During these periods, the candidates reduce their activities aimed at the persuadables, like running TV ads. Instead, they reorganize their campaigns to complete the primary phase, and set up staffing and strategy for the general election.

During this time, the campaigns continue to engage with their supporters in hopes of amassing a large war chest and an army of volunteers to take on the opponent.

Campaigns also use this lull to expand their databases. Data about the public is as vital as money. It’s not enough to know a supporter’s name and address: Understanding their likes, habits, political behavior and even psychological predispositions can give a deeper picture, letting campaigns identify people with similar characteristics as potential supporters.

That’s what the now-reviled campaign data analysis firm Cambridge Analytica promised to do.

Similarly, characterizing persuadables and opponents can help campaigns target their efforts efficiently. The Trump campaign identified opponents to his campaign to target them with ads meant to discourage them from voting.

For the next few months, here are three things to watch.

Social media

As I explain in my book, since 1996 the Democratic and Republican party machines have been honing their strategies of communicating through digital media. They use Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat alongside YouTube, email and websites in an integrated communications system.

Even though the digital platforms allow easy two-way communication on blogs, forums and social media, that’s not what the campaigns are looking for. They don’t want long, drawn-out policy debates on their pages. Instead, they want to use interactive elements of the internet to convert supporters and get them to give up data about themselves.

The social media accounts are the workhorses to cultivate supporters and draw them to the campaign’s website, which is home base. That’s where campaigns can deliver their most direct messages and collect that valuable data about their supporters.

The campaigns use a tactic I call “controlled interactivity” on social media to entice followers to share information about themselves. On the campaigns’ official feeds, they post polls, hawk merchandise and push an endless stream of requests to sign up for email or to give money. Anytime someone interacts with one of those posts, the campaign gets a little bit more data. For example, Trump’s Facebook page features posts about his virtual events with “Team Trump.” A click on the “join” link goes to the campaign website, where visitors are asked to give up their personal information: name, address, phone number and email address. When they do, the campaign just got a new supporter to target.

Mobile apps

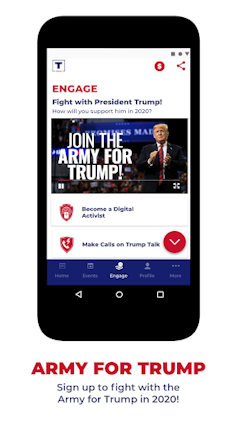

Both Trump and Biden have launched mobile applications for iOS and Android devices. It’s worth their campaigns’ money and effort because it can keep supporters energized, and collect more data.

Only supporters – and perhaps curious reporters and opponents’ campaign staff – will download and seriously use the app. Once downloaded, its function is to make supporters feel like an insider by giving them news and “inside looks” at the campaign, tools to donate money and opportunities to become local organizers. Trump’s app encourages users to “Become a Trump Team Leader” by registering voters and knocking on doors in their community.

Most of these political apps are also designed to help grow campaigns’ voter contact lists. Not only do they collect the user’s own contact information but they often seek to access the phone’s entire contact list. These apps may also want access to photos, the user’s social media accounts and location information.

All of this data gives campaigns more extensive pictures of who their most ardent supporters are. That helps them target others with similar characteristics, to bring them into the campaign fold.

Paid ads

On television, most ads target persuadables in an effort to influence how they think about the candidates. That’s because television ads do not allow for the degree of fine-grained or micro-targeted advertising that digital media ads provide.

TV ads blanket whole regions, while social media ads pinpoint-target specific people based on the desirable traits that the campaign is after – typically people who look like supporters. This is where all that data comes in. Social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Google allow advertisers to create “look-alike” campaigns, where the advertiser feeds the social media company the names and email addresses of known supporters. Then the company’s proprietary algorithms find the email addresses that match, analyze the known Facebook profiles for their interests and behaviors and then find other users with similar likes, interests and behaviors.

Those people get targeted with ads; if they click on the poll or buy a hat that’s advertised, the campaign grows its support base while also improving its data about who is likely to respond positively to future ads. Political watchers have even speculated that this technique helped Trump win in 2016.

With the conventions now postponed to the end of the summer, Trump and Biden have more time to grow their databases, their financial war chests and their supporter bases.

Although it may seem an unprecedented campaign season that the candidates were ill-equipped for, the truth is that digital campaigning has been well-honed over six election seasons. They just need to do more online than they had planned for.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]

![]()

Jennifer Stromer-Galley, Professor of Information Studies, Syracuse University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters