How Coronavirus Exacerbates the Drug Shortages in Canada

Drug shortages cause all sorts of problems.

COVID-19 has exposed and magnified weaknesses within health-care systems. Drug shortages, which are a growing problem in Canada, may be one example of this.

Shortages hinder patients’ ability to effectively manage chronic diseases, leading to unnecessary harm. They also complicate the work of health-care providers, such as pharmacists, who must spend considerable time trying to find difficult-to-obtain drugs, and physicians, who have to prescribe alternative drugs to replace those that are unavailable. Shortages may also increase costs if alternative treatments are more expensive.

Potential contributors to shortages

Disruptions in the supply chain due to COVID-19 may cause shortages because many drugs and the raw ingredients used to produce them come from India and China. India has started to ban some drug exports due to shortages in its own country.

Supply-side pressures are also caused by increasing consolidation in the pharmaceutical industry, which means fewer suppliers and manufacturing facilities and thus fewer alternative sources for drugs. Given that most shortages are of less expensive generic drugs, some speculate that manufacturers intentionally limit the production of less profitable products to drive up sales of expensive brand name drugs.

COVID-19 may also produce demand-side shortages. Manufacturers are struggling to keep up with demand for the sedatives required by patients on ventilators. Large volumes of these drugs will also be necessary when Canadian hospitals catch-up on elective surgeries cancelled due to COVID-19. For example, two manufacturers of one such sedative, propofol, have reported recent shortages.

Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, which were touted as treatments for COVID-19, are in sufficiently high demand that professional regulatory bodies have issued warnings about inappropriately prescribing these products. Since March 15, six azithromycin products and one hydroxychloroquine manufacturer have reported shortages in Canada. The latter of these affects patients who take hydroxychloroquine to treat arthritis and lupus.

Prevalence of shortages

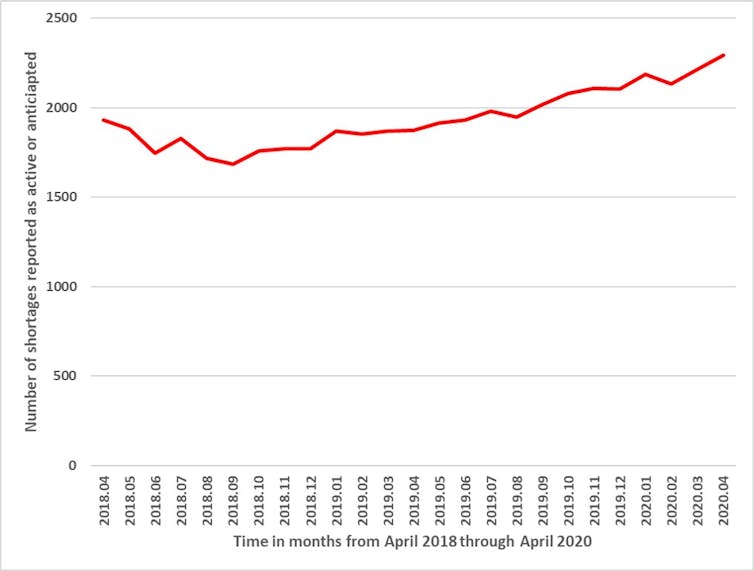

In order to enhance tracking of and responsiveness to drug shortages, Health Canada has required manufacturers to report shortages since 2017. Shortages have been steadily increasing over the past two years, with 2,023 products in shortage as of April 2020.

Some of this effect may be attributable to the increasing number of products that are added to the pharmaceutical market each year. This suggests that Health Canada must continue to increase its capacity to monitor and address shortages to correspond with the growing number of products in active use. In its role as federal drug regulator, Health Canada may help drug manufacturers address shortages by reviewing alternative suppliers, processes, facilities and production locations.

Although the full effects of COVID-19 on drug shortages are not yet known, it is notable that manufacturers reported 221 new shortages in April 2020, compared to 148 in March, 59 in February and 104 in January. In other words, a recent increase in shortages, which could be attributable to COVID-19, may worsen existing problems with shortages.

Response to shortages

Pharmacists reported a rush to fill prescriptions when physical distancing measures took effect, with some patients requesting a six-month supply. In response, Health Canada discouraged drug stockpiling and the Canadian Pharmacists Association and provincial governments strongly encouraged pharmacists to limit patients to a 30-day supply of their prescriptions.

Although this may help to address shortages by moderating demand, it increases the cost of drugs for individuals who may incur additional dispensing fees with each visit. This disproportionately affects those who are unemployed and who have lower incomes. It may also require more frequent visits to pharmacies, which can be dangerous for seniors who are at increased risk for COVID-19 and tend to use more prescriptions. When this 30-day restriction is lifted, the elevated demand may further contribute to shortages.

The federal government has implemented several measures to address COVID-related shortages. On March 25, it authorized the passage of regulations necessary for “preventing shortages … or alleviating those shortages or their effects, in order to protect human health.”

This legislation also allows the government to grant a manufacturer a license to produce a drug, even if another manufacturer holds the patent for that product. Although these licences could theoretically increase supply, practical challenges may limit their utility. For example, alternative suppliers may similarly be unable to obtain raw ingredients from the same foreign suppliers.

A more practicable solution may be the import and sale of drugs that have not yet met all Canadian regulatory requirements, which is permissible following an order by the minister of health. However, this exceptional process is only available for particular drugs that meet certain manufacturing standards.

While the federal government’s efforts may help to mitigate shortages during COVID-19, it should also seize this opportunity to develop long-term solutions to shortages, which have affected the Canadian drug market for years. Due to the globalization of pharmaceutical manufacturing, the government must work with both industry and other countries to rapidly identify and respond to disruptions in the supply chain, so that Canadians have uninterrupted and reliable access to safe drugs. Given the pressures caused by COVID-19, now is a pivotal time for the government to act.

![]()

Lorian Hardcastle, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Law and Cumming School of Medicine; Member, AMR One Health Consortium, University of Calgary and Reed F Beall, Assistant Professor, Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters