John Brown's Legacy: Violent Abolitionist or Moral Crusader?

John Brown was a leading white abolitionist who engaged in many peaceful efforts to free and assist enslaved African Americans before the Civil War. But his methods eventually shifted.

One of the most underappreciated figures in the nation’s history, John Brown, has been introduced to Americans by the recent Showtime series “The Good Lord Bird,” based on the James McBride novel of the same name.

Too often dismissed as a failed zealot, Brown was an unconventional anti-slavery leader who blazed a trail that Abraham Lincoln would follow just a few years later.

Commentators then and now are more likely to see differences between Lincoln’s and Brown’s approaches to civic leadership. Lincoln was cautious and deliberate; Brown was a revolutionary on fire.

Though this contrast is instructive, there’s another way to look at both men. In the end, they were both moral crusaders who exercised uncompromising moral leadership.

Unwavering commitment

John Brown was a leading white abolitionist who engaged in many peaceful efforts to free and assist enslaved African Americans before the Civil War.

But his methods eventually shifted. In 1856, a 55-year-old Brown joined two of his sons in the Kansas territory and led anti-slavery paramilitary forces to victory in the violent period that became known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

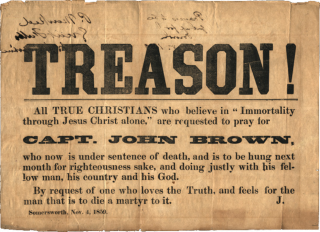

In 1859, Brown’s abolitionist efforts culminated in a raid on a federal armory at Harpers Ferry in what is now West Virginia. This was the first step in Brown’s broader plan to emancipate slaves throughout the South. The attempt was unsuccessful, and Brown was captured, tried and hanged shortly thereafter.

In a speech delivered at Harpers Ferry more than 20 years later, abolitionist Frederick Douglass claimed that “John Brown began the war that ended American slavery and made this a free Republic.”

Defending his positive view of Brown’s turn to violence, Douglass explained that Brown was an “agent” of God’s “retributive justice.” Douglass argued that a higher logic – what Brown referred to as the “law of God” – provided a special justification and vindication for Brown’s actions.

As I have explored at length elsewhere, such higher-law arguments to justify actions are more than mere rhetoric in the service of political causes. They have been carefully developed throughout the history of political thought by some of the most profound thinkers from around the world, and from ancient times to our own.

Brown possessed – or, perhaps better, was possessed by – a clarity of moral principle that simply ruled out inaction or compromise in the face of grave injustice. One of Brown’s refrains was “Whenever there is a right thing to be done, there is a ‘thus saith the Lord’ that it shall be done.”

When questioned about his motives by federal authorities following his capture, Brown said simply: “We came to free the slaves, and only that.”

In stark contrast to the great American political leaders of his day, Brown shunned compromise and accommodation and instead was driven by an unwavering commitment to moral principle.

Statesman versus radical

The greatest American political leader of the mid-19th century was Abraham Lincoln, who was elected to the presidency the year following Brown’s famous raid. If Brown began the war that ended slavery, Lincoln is the man who finished it.

The inextricable link between the two anti-slavery leaders was forged, in fact, years earlier and hundreds of miles away on the plains of Kansas. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 and its repeal of the Missouri Compromise was “like a fire bell in the night” for both Brown and Lincoln. By allowing slavery to be legalized by popular vote in new states north of the Missouri Compromise line, this law sparked a flood of settlers to the Kansas territory who were determined to tip the scales either for or against slavery.

Given the highly polarized nature of the issue of slavery by this time, many of these new settlers were prepared to engage in violence to influence the outcome of the vote. The ensuing conflict drew Brown into direct, violent confrontation with proponents of slavery for the first time.

And the federal government’s new openness to slavery’s extension beyond the existing states transformed the issue of slavery from being a “minor question” in Lincoln’s mind to the centerpiece of his political thought and career.

While debating political rival Stephen Douglas a few years later, Lincoln stated the importance of moral principle to his campaign with Brown-like simplicity and clarity:

“The real issue in this controversy is the sentiment on the part of one class that looks upon the institution of slavery as a wrong, and of another class that does not look upon it as a wrong.”

In other words, according to Lincoln, abstract legal doctrines relating to states’ rights or the nature of the constitutional union were, at best, secondary. Opposite opinions about the morality of slavery drove the controversy that would result in the Civil War.

And yet, in his Cooper Union Address in 1860 – the speech that would catapult him to the presidency – Lincoln was at pains to distance himself from Brown.

“John Brown was no Republican,” said Lincoln, the party’s leader. He was a deluded madman who convinced himself that he was “commissioned by Heaven” to liberate the enslaved.

Lincoln presented himself as the clearheaded, prudent statesman who would work within the legal framework to combat the moral evil of slavery; Brown was the dangerous radical who would indiscriminately destroy both.

Distance vanishes between Lincoln and Brown

Yet five years later, as Lincoln unknowingly entered what would be the final weeks of his life, his differences with Brown appeared to narrow.

Lincoln had fought tirelessly in January 1865 for the passage in the House of Representatives of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, using every tool at his disposal to influence reluctant members.

In the first week of February, Lincoln approved Congress’ resolution to move the 13th Amendment forward to ratification and rejected a Confederate peace proposal. As the Civil War raged on and thousands of additional lives were lost, Lincoln seemed to focus his energy not on securing the peace, but on abolishing slavery.

Lincoln had achieved just what Brown had attempted in Kansas and at Harpers Ferry: abolition through violent conflict with slaveholders.

Lincoln’s second inaugural address the following month, moreover, framed the Civil War in precisely the same terms Brown had used to justify his actions. In this speech, Lincoln casts himself as a mere agent in the service of God’s providential plan to punish the evil of slavery.

With the 13th Amendment on its way to ratification, all that remained was the fulfillment of divine justice, Lincoln said – a mystical moment of equilibrium when “all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk,” and “every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.”

In his final words on the defining event of his political career, the distance between Lincoln and Brown all but vanishes. Brown’s “thus saith the Lord” echoes clearly in Lincoln’s concluding prayer: “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

Lincoln appreciated the prudent statesmanship of pre-Civil War politicians such as Henry Clay, but the defining quality of Lincoln’s leadership was forged of less pliable stuff. Lincoln was ultimately more crusader than compromiser.

In this way, he and John Brown share a model of moral leadership that is still worthy of study, even in the 21st century.

![]()

Adam Seagrave, Associate Professor of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.'

Image: Wikimedia Commons