The Peace Deal That Ended World War I Was Completely Racist

The racism that is now the target of protest across the globe is rooted in the tragic choices of leaders seeking to roll back change a century ago.

The racism that is now the target of protest across the globe is rooted in the tragic choices of leaders seeking to roll back change a century ago.

Nearly all historians now agree that at the end of World War I, the choice to return to an imperialist world order by the victorious Allied, or Entente, powers – France, Britain, Russia, Italy, Japan and the United States – was a historic error. It not only prepared the ground for the rise of fascism in Europe, but also sparked decades of political violence in Asia and Africa by people denied their rights and humanity.

As World War I ended in November 1918, the Spanish Flu pandemic swept across the globe, killing more than 50 million people. Most vulnerable were soldiers living in crowded barracks and their families back home, where hunger weakened immunity.

Like today, the effect of pandemic was aggravated by economic recession and unemployment. Worse, the people of the defeated German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman empires suffered chaos under political collapse.

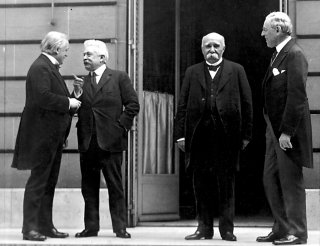

Amid these multiple crises, the Paris Peace Conference opened in January 1919. American President Woodrow Wilson personally traveled to Paris to ensure that the conference would make the world “safe for democracy.”

Wilson had promised a new era of peace and justice in his famous Fourteen Points statement of war aims, which included an end to secret treaties, the curtailment of colonial empires, the right of all people to choose their own government and a League of Nations to adjudicate international conflicts.

In 1920, like 2020, race became the pivot of a historic turning point. In both moments, world leaders faced a choice: to restore the previous status quo that had produced the crisis – or to embrace the need for a new world order.

The European members of the Entente powers at Paris – Britain, France, and Italy – ignored Wilson’s call for world order based on law and rights. With the implementation of the Treaty of Versailles in January 1920, they chose to restore a racial hierarchy across the globe, extending their colonial rule over territories once held by the defeated German and Ottoman empires in Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

The treaty, which included establishment of the League of Nations, betrayed not only Wilson’s ideals, but also the Entente’s nonwhite allies and the colonial soldiers who fought in the “war to end all wars.” The racial injustice of the 1919-20 peace settlement sparked decades of political violence – not only in the colonized Middle East, Africa and Asia, but also in the United States.

Journey to Paris

In January 1919, activists from around the world traveled to Paris despite risks to their health. They embraced Wilson’s Fourteen Points as a chance to remake a broken world system of imperial rivalry that had led to World War I and the deaths of 10 million soldiers and 50 million civilians.

Among those activists was NAACP leader W.E.B. Du Bois, who had fought against the spread of racist, segregationist Jim Crow laws from southern states to the North. He now feared that a similar legal double standard might be imposed in international law, to the detriment of African rights.

Du Bois asked to join the American delegation at Paris, but the Wilson administration refused him. Wilson feared that Du Bois’ call for racial equality might spoil his negotiations with the other conference leaders – prime ministers of Britain, France and Italy – who ruled most of Africa as colonies.

Claiming rights

Undeterred, Du Bois organized a Pan African Congress to defend Africans’ rights. He understood, as others did in Paris, that racial inequality was the foundation of the old imperial world order.

Like Du Bois and his African allies, Arabs and Egyptians claimed their right to sovereignty. But they found that the Entente leaders also considered Arab Muslims a lower species of human, unfit for self-rule.

Prince Faisal of Mecca gained entry to the conference because his Arab army had fought against the Ottoman Turks alongside Britain, with the understanding that Arabs would gain an independent state. But the British broke their promise and denied independence to Faisal’s Syrian Arab Kingdom. They instead joined French colonialists to divide Arab lands between them.

Asians, too, were regarded as an inferior race. Japan had fought alongside the victorious Allies and had won a leading role at the conference.

But when the Japanese delegation proposed a racial equality clause for the Covenant of the new League of Nations, the conference’s white leaders rejected it.

Racial inequality codified

The Covenant of the League of Nations, drafted by those same leaders at Paris in 1919, codified the inequality of races in international law. Article 22 denied independence to Arabs, Africans and Pacific Islanders once ruled by the Ottomans and Germans.

In the condescending language of moral uplift, the article designated them as “peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world.” Therefore, they would be placed under temporary European rule as “a sacred trust of civilisation.”

In other words, the League of Nations would administer temporary colonies, called mandates, to tutor uncivilized (nonwhite) people in politics. Racial inequality was enshrined in the very institution, the League of Nations, that was to ensure the governance of international law.

The mandates were imposed by gunpoint, with no pretense to respect self-determination. In July 1920, the French army occupied Damascus, destroyed the Syrian Arab Kingdom and sent Faisal into exile. Likewise, the British battled mass opposition to claim its mandates in Iraq and Palestine. Meanwhile, South Africa imposed a brutal racist regime upon southwest Africa.

Racial exclusion from the club of so-called civilized nations provoked anti-colonial movements for the rest of the 20th century.

The president of the Syrian Arab Kingdom’s Congress, Sheikh Rashid Rida, foresaw violent consequences in his 1921 appeal to the League of Nations.

“It does not befit the honor of this League, which President Wilson proposed to include all civilized nations for the good of all human beings,” he wrote, “for it to be used as a tool by two colonial states. These states seek to use this Assembly to guarantee … the subjugation of peoples.”

Rida prophetically warned that “Syria, Palestine, and other Arab countries will ignite the fires of war in both the West and the East.” The bitter sheikh turned against European liberalism and inspired the founding of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt in 1928.

In the later 20th century, this racial exclusion of Arab Muslims inspired the violent Islamist movements that drew the United States into seeming endless conflict in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria.

Jim Crow stays

In the United States, racial hierarchy was similarly reimposed by violence. Black veterans returned from Europe to confront lynching and race riots.

[The Conversation’s newsletter explains what’s going on with the coronavirus pandemic. Subscribe now.]

The link between the American racial order and the new world order was made explicit by President Wilson’s adviser, Colonel Edward M. House. He advised Wilson that racial equality would cost him votes in the South and California. Worse, such a clause could empower the League of Nations to intervene in the United States against Jim Crow laws.

In March 1920, the U.S. Senate rejected American membership in the League of Nations precisely because clauses on transnational law enforcement and collective security threatened U.S. sovereignty.

It is no accident that the current crisis in the U.S. has come to focus on racial injustice. Among its several sources are the decisions made 100 years ago by white men from powerful countries who believed maintaining their dominance was more important than seeking peace through justice.

![]()

Elizabeth Thompson, Professor and Mohamed S. Farsi Chair of Islamic Peace, American University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Wikimedia