Torn Between Russia and the West, Where do Young Belarusians Stand?

Survey results show that young people are turning away from Russia to look towards Europe.

Since Belarus’s disputed presidential elections on August 9, hundreds of thousands of Belarusians have taken to the streets. Their protests have been met with extreme police brutality.

According to the country’s electoral commission, Alexander Lukashenko won 80% of the vote share, and his principal opponent, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, received 10%.

While some older people, particularly women, have taken to the streets, young people have been at the forefront of the protests. In early September, teenagers were even filmed being removed from school by security services amid student protests.

At the Berlin-based Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS), we’ve been conducting surveys among young Belarusians since 2019. One survey in late June 2020, just before the election, found that support for Lukashenko was around 10% among young people.

Our survey results also show that young people are turning away from Russia to look towards Europe.

Between Russia and Europe

Separate research from early 2020 found that Belarusians appear content with their country being slightly pro-Russian. But people under 40 were significantly more likely to want closer relations with the west.

The ZOiS’s own online surveys have been asking young people what kind of relationship they want Belarus to have with the EU and Russia. Our surveys include 2,000 young people aged between 16 and 34, though the June 2020 survey included young people of voting age between 18 and 34. The respondents, who live in the country’s six largest towns, were included based on quotas for age, gender and city of residence.

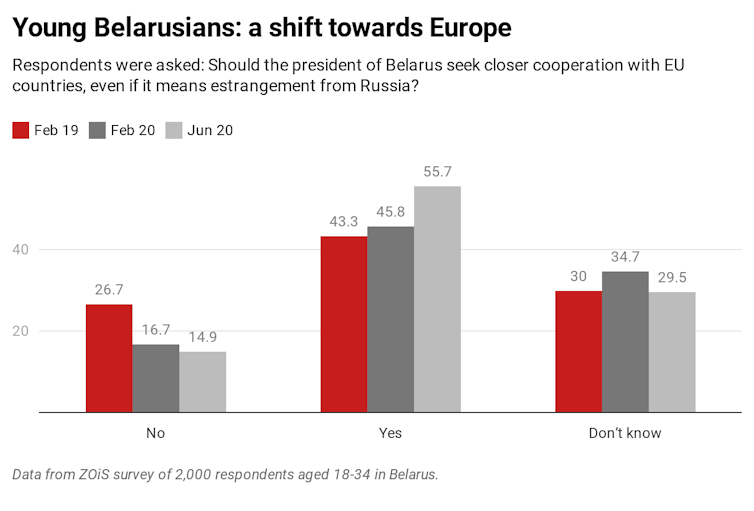

Since the ZOiS survey was first conducted in 2019, young Belarusians have significantly shifted away from wanting closer relations with Russia and instead are seeking closer relations with EU countries. Facing the trade-off between closer EU relations and worsening relations with Russia, 55% of young people now wish for closer relations with the EU.

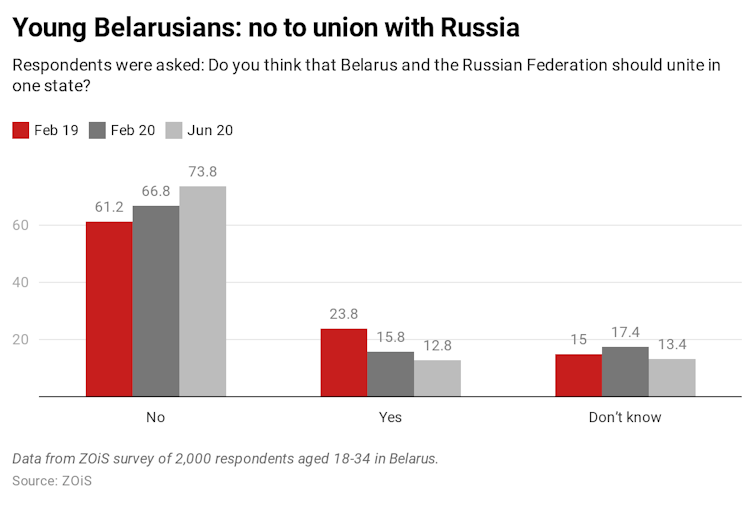

Asked whether Russia and Belarus should unite as one state, more than 70% of young Belarusians were opposed to the prospect. A union between the two countries was the ultimate aim of the 1999 Union State treaty which intends to create a federation between Belarus and Russia that would harmonise their laws, state symbols, economy and politics.

Our results showed a clear division of views between those living in the east and west of Belarus, with those living in the east, near the Russian border, is significantly more critical of the EU and favourable to Russia. We also found that the better-educated respondents and those who don’t use any state media were particularly in favour of closer relations with the EU. Those with a lower level of education and no political interest were more likely to want closer relations with Russia.

Language and identity

The growth in political interest and discontent predates the August election and can be linked to the mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic, which laid bare the ineffectiveness of the Belarusian state.

Read more: Belarus election: why strongman Alexander Lukashenko faces unprecedented resistance

But the current protests also represent a national awakening. Many of the protesters have draped themselves in red and white, colours reminiscent of the independent Belarusian People’s Republic that existed for less than a year after March 1918. Its white-red-white flag returned briefly after the Soviet Union’s collapse, but after a referendum in 1995 it was replaced by the country’s current green-red flag resembling the Soviet Belarusian flag.

The question of Belarusian identity is, therefore, crucial to the current protests. The Belarusian language has been largely marginalised since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Lukashenko himself prefers speaking Russian, and Belarusian has become a statement of opposition. The young Belarusians we’ve surveyed overwhelmingly speak Russian in their daily interactions, although a third consider both to be their native languages.

Still, we found that young people have no strong desire to speak more Belarusian. Instead, more than a quarter of our respondents said they didn’t care, suggesting that the language issue was not a crucial political and social question for young people. People living in towns in the east were even less likely to have a desire to speak more Belarusian. But those respondents over 25-years-old, the better educated ones and women were significantly more likely to express a desire to speak more Belarusian.

Still, protesters are calling for the autonomy to make a political choice. They have expressed this using traditional Belarusian symbols, including elements of medieval history such as a knight, which refer to the time of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th-18th centuries.

Visions of Europe

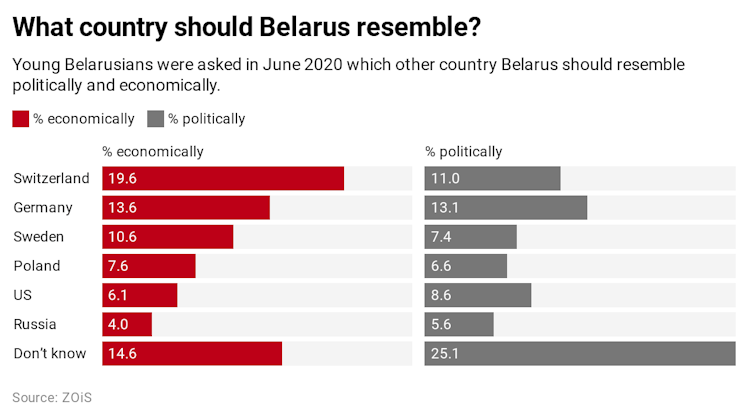

In June 2020, we also asked our respondents what country Belarus should resemble, both politically and economically. Our initial analysis shows that economically, Switzerland was the most frequently mentioned country and was also the second most desired in political terms. Germany came second economically, and first politically, with Sweden third in economic terms.

All this shows how young Belarusians are increasingly oriented towards European countries. Their turn away from Russia, and the Soviet values associated with it, is striking. The continuing mobilisation is, therefore, part of a new political awakening which is seeking to establish Belarus’s independence both politically and symbolically.

![]()

Félix Krawatzek, Senior Researcher at the Centre for East European and International Studies and Associate Member of Nuffield College, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters