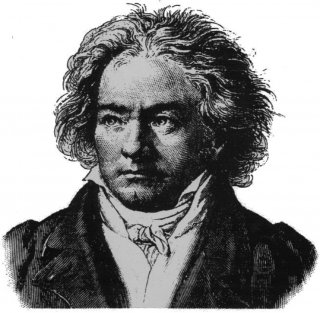

Was Beethoven Black?

The notion of the great composer’s secret ethnicity has circulated at the fringes of the media and scholarship for more than a century.

The year 2020 marks the 250th anniversary of Ludwig van Beethoven’s birth, and in mid-June this year, he started trending on Twitter. Perhaps it wasn’t so strange that Beethoven was popping up on social media platforms, but what was unusual and certainly unforeseen: the claim that “Beethoven was Black.”

Where did this idea come from? The circulation of this trope has no doubt been catalyzed by recent events — namely, the death of George Floyd and the subsequent ascendancy of Black Lives Matter — and by the rigorous debates over race that have since permeated mainstream and social media.

As it turns out, though, Beethoven being of African descent is not a new idea: the notion of the great composer’s secret ethnicity has circulated at the fringes of the media and scholarship for more than a century.

Anecdotal evidence

The original theory of “Black Beethoven” first appeared in the popular press in the early 20th century. Much of the anecdotal evidence for this claim is based on contemporary accounts, many of which were collected in Sex and Race, published in 1944 by historian and journalist Joel Augustus Rogers. These accounts present the composer as having the features and complexion of a Black person.

Beethoven was described by some contemporaries as “dark,” “swarthy” or as a “Moor.” This latter term, “Moor,” was used in the 18th and 19th centuries to refer to a Muslim person from North Africa or the Iberian peninsula, or more generally a dark-skinned person, and has generated particular interest and conjecture about Beethoven’s race.

Historians have suggested that a member of the Habsburg royal family, Prince Nicholas Esterhazy I, even called both Beethoven and Joseph Haydn “Moors,” supposedly because of their dark complexions. Such accounts are likely specious. But one possibility is that, if the prince used this term for Haydn (whom he employed as a court composer) or for the young Beethoven, he was using it idiomatically: that is, “Moor” could be a dismissive epithet for a servant.

For some scholars, Beethoven’s music itself, its rhythmic complexity — specifically its syncopation — points towards his hidden ethnicity, as it suggests a knowledge of West African musical practices. A few writers even go so far as to suggest the presence of reggae- and jazz-like rhythms in his piano sonatas. Beethoven was Black because his music “sounds” Black; in other words, notwithstanding the unlikeliness of his familiarity with African music or that syncopation was commonplace in European music at that time.

Others cite Beethoven’s friendship with the Afro-European violinist and composer George Bridgetower as somehow evidence of the composer’s own multiracial identity.

Friendship with Bridgetower

Ultimately, there is no reason to believe that Beethoven was Black: the genealogical evidence going back to the 1400s shows unambiguously that Beethoven’s family was Flemish. Speculative anecdotes from the early 19th century about his swarthy complexion, broad nose and coarse, black hair are unsourced and racist.

The suggestions that jazzy syncopations in his music somehow derive from African genetics are anachronistic and absurd. Calling a white person with a darker complexion a “Moor” was also not uncommon in the 19th century: Karl Marx’s companions referred to him as “the Moor,” not because of his race, but apparently because of his thick black hair and voluminous black beard.

Pursuing the idea that “Beethoven was Black” both whitewashes and blackwashes music history, as African American studies scholar Nicholas Rinehart has observed. Blackwashing makes important historical figures Black for the sake of seeking to validate the cultural contributions of people of colour. Whitewashing refers to the practice of valourizing Black musicians and composers by giving them white referents: a gifted Black composer becomes, for example, the “The Black Mozart” or the “African Mahler” — a mere “footnote” to a white composer, in Rinehart’s words.

Ultimately, it may be Beethoven’s friendship with Bridgetower, and not internet memes, the blogosphere or the Twitterati, that provides a way to productively approach racial politics in classical music.

How many of us, in the 21st century, are even aware of Bridgetower, who was an accomplished and well-known violinist in England and Europe during his lifetime and was also the original dedicatee of Beethoven’s famous “Kreutzer” sonata for violin and piano? As the African-American writer and poet laureate Rita Dove insists, Bridgetower might have become a “household name’ in the 19th century musical world had he not been Black.

Forgotten and overlooked

Efforts to make Beethoven Black — an awkward dance of trying to examine the issue of race and classical music while simultaneously maintaining the canonic centrality of Beethoven — ultimately obscure the existence and contributions of actual people of colour in the history of music. Black composers like Joseph Boulogne, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and William Grant Still, Rinehart argues, have simply been "forgotten, overlooked and overwritten.”

The “Beethoven was Black” trope trending on Twitter serves the interests of current racial politics and social justice movements like Black Lives Matter, just as it served the Black Power movement in the early 1960s: Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael both invoked Beethoven’s would-be Moorish ancestry to claim that he — along with other historical figures, including Hannibal, Columbus and Jesus — was a Black man.

If the genealogical or phenotypical pursuit of “Black Beethoven” leads to a dead end, it nonetheless emphasizes the importance of past and ongoing work by Black scholars to research and document the history of music and race. Just as musicology finally embraced feminist and gender theory in the 1990s, providing new and more inclusive ways to examine the meaning and experience of classical music, the recent conversations about “Black Beethoven” points in the direction of fruitful and necessary avenues of inquiry into music history.

This, in turn, may help inform our contemporary cultural dialogues in these turbulent times.

![]()

Alexander Carpenter, Professor, Department of Fine Arts, University of Alberta

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Wikmedia