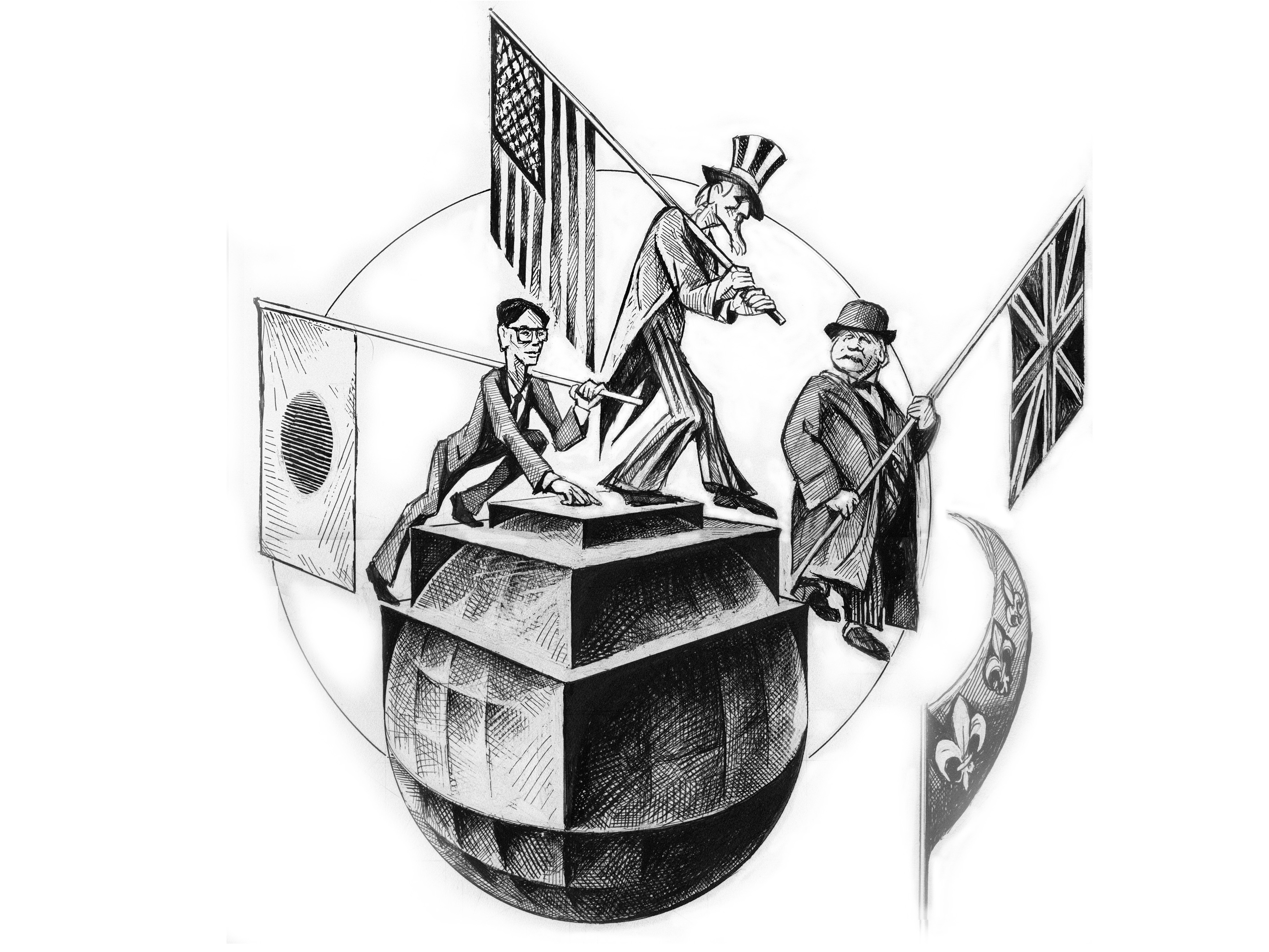

Our Restrained Great Powers

The current lack of powerful nations with revisionist aims is both historically rare and worthy of celebration.

Paul Kennedy, the dean of great-power historians, has a very good op-ed in Wednesday’s International Herald Tribune in which he attempts to put our current crop of leading nation-states in perspective. After running through some of the spats currently consuming world leaders—from the U.S.-Russian fracas over Edward Snowden to the U.K.-Spanish feud over Gibraltar—he asks:

To historians of world affairs, including this one, the only proper response to this litany of spats, pouting and injured pride is to ask: “Is that all?” Are these the only issues which divide and upset the Great Powers as we enjoy the second decade of the 21st century? And, if so, shouldn’t we count ourselves lucky?

The answer, of course, is yes, as he goes on to explain. He reminds us that it wasn’t all that long ago that the great powers of the twentieth century plunged the globe into two devastating world wars, each resulting in millions upon millions of casualties. The second killed a jaw-dropping 2.5 percent of the total world population at the time. In contrast, he writes, today’s great powers—consisting of the United States, China, Europe, Russia, Japan, India and Brazil, in his mind—are not the world’s real “troublemakers.” That is, none of them wishes to undo the basic nature of the international system. The real dangers to peace and stability, he says, lie elsewhere:

in the unpredictable, overmilitarized lunatic asylum that is North Korea; in an Iran that sometimes seems to be daring an Israeli air strike; in a brutal and autistic Syrian regime; in a Yemen that both houses terrorists and pretends to be killing them off; and, far less purposefully, in the conflict-torn, crumbling polities of Central Africa, Egypt and Afghanistan, and many nations in between. Here are the world’s problem cases.

If there are neurotic Kaiser Wilhelms or bullying Mussolinis or murderous Stalins around today, they are not — thank heavens — to be found in Beijing, Moscow or New Delhi.

It’s possible to quibble with Kennedy’s piece around the edges. Is Brazil really a great power right now? Is Europe a single, unitary actor in global affairs? And might China, as its economic and military strength increases over the next several decades, develop correspondingly more expansive aims as well? But the core argument is sound: none of today’s great powers, however one defines them, currently appear to be revisionists in the sense of seeking broad territorial conquest or seeking to change the rules of the liberal international order.

Kennedy doesn’t say this explicitly, but his piece serves as a direct rebuttal to the threat inflation that often comes from Washington’s leaders of both parties, many of whom often declare breathlessly that we live in a uniquely dangerous world. Senator Lindsey Graham is perhaps the best example, asserting just a few weeks ago that “we live in the most dangerous times imaginable.” We don’t. In fact, these are far from the most dangerous times imaginable—they’re not even the most dangerous times in recent history. Nor, for that matter, did the annals of ancient history represent a particularly safe, peaceful era, as Steven Pinker shows in The Better Angels of Our Nature.

Kennedy doesn’t say this explicitly, but his piece serves as a direct rebuttal to the threat inflation that often comes from Washington’s leaders of both parties, many of whom often declare breathlessly that we live in a uniquely dangerous world. Senator Lindsey Graham is perhaps the best example, asserting just a few weeks ago that “we live in the most dangerous times imaginable.” We don’t. In fact, these are far from the most dangerous times imaginable—they’re not even the most dangerous times in recent history. Nor, for that matter, did the annals of ancient history represent a particularly safe, peaceful era, as Steven Pinker shows in The Better Angels of Our Nature.

This is a point that’s easy to dismiss or even mock when any day’s headlines might contain news of a foreign tragedy like the ongoing and horrific mass killings in Egypt. Obviously, it’s of no comfort to Egyptians, Syrians or others suffering elsewhere around the world. Nevertheless, it’s an essential fact for trying to make sense of the threats that the United States and the world face today. None of the “problem cases” that Kennedy highlights, and that dominate international news coverage on a day-to-day basis, are threats of the magnitude that a truly revisionist power would pose.

What this situation requires from the big powers, Kennedy observes, is “self-restraint, year after year, decade after decade.” It doesn’t represent an end to war, but it means that the great powers work to ensure that the conflicts that do occur—whether involving themselves or their client states—remain local. No doubt “Comparatively Less War Now” doesn’t make for an inspiring bumper sticker. For the moment, however, it’s a slogan that appears to be true, and we should hope it stays that way.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Van Howell. CC BY-SA 3.0.