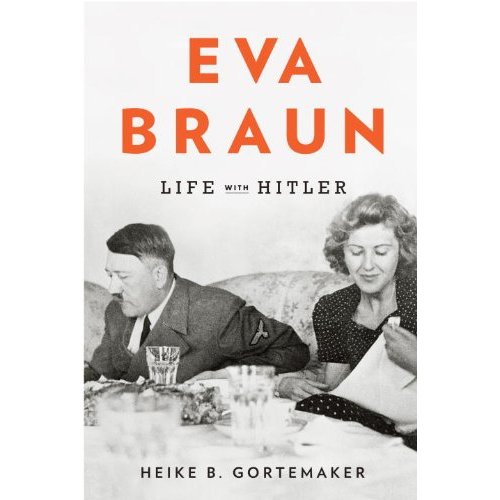

Adolf & Eva

Mini Teaser: Wild speculations by amateur psychoanalysts painted Hitler as a pervert of every caste and creed. A new book unearths the surprisingly mundane truth: he adored the young, fun-loving, Elizabeth Arden–wearing, cigarette-smoking Eva Braun.

Nazi ideology portrayed women as essentially passive, modest, simple and undemanding creatures, whose role was to adore their menfolk. Braun was no such woman. As her failed suicide attempts showed, she was prepared to go to some lengths to get what she wanted. Her position at the Berghof, in which she asserted her dominance over the much-older would-be first ladies of the Reich, testified to her strength of personality. During the war, visitors noted how she became more self-confident, signaling to Hitler to shut up when he had launched into one of his interminable after-dinner monologues, or asking loudly what the time was when he showed no sign of retiring for the night. Still only in her twenties, she had become a figure to be reckoned with in Hitler’s inner circle.

Eva failed to conform to the Nazi ideal of womanhood in other ways too. A visitor to whom she was presented as the “housekeeper” at the Berghof reported disapprovingly that Braun changed her dress several times a day. She did not, he noted severely, conform to the “ideal of a German girl,” who was supposed to be “natural” in appearance. She bleached her hair and always wore makeup (Elizabeth Arden was her preferred brand). Moreover, as soon as Hitler left his Bavarian retreat, her mien changed—she smoked cigarettes (not only did Hitler himself not smoke, he also banned smoking around him), devised amusements for her friends, watched foreign movies, held parties, did gymnastics in a swimsuit, sunbathed in the nude and generally let her hair down.

Women were discouraged from pursuing professional work in Nazi Germany, but Hitler recognized Eva’s claim to be a professional photographer—she not only took numerous, often very good photos but also developed and printed them herself—by calling her the “Rolleiflex girl.” One of the few gaps in this otherwise comprehensive study is Görtemaker’s failure to discuss the extensive home movies Braun filmed at the Berghof; these are a significant source for our knowledge of the Third Reich leaders and their relations with one another. Braun’s color film of Hitler and his entourage is of rare immediacy, somehow, to the twenty-first-century eye, far more real than film shot in black and white. Some of it has been subjected to automated lip-reading technology, and in one particularly creepy moment, Hitler, while being filmed by Braun, begins to flirt with the woman behind the camera, giving those who view it the uncomfortable feeling that Hitler is flirting with them.

FOR ALL Eva’s self-assertion, most of the men in Hitler’s entourage who knew her portrayed her as an unassuming little thing, unaware of the big, wide world outside. Much of what is known about her comes from postwar reminiscences, notably those published by Albert Speer. Görtemaker shows once more how unreliable Speer’s self-serving recollections were, like those of many others who knew Hitler’s eventual wife. It was, after all, in their interest to suggest that she was naive and nonpolitical, that life in the place where she spent most of her time, in Hitler’s mountain retreat on the Bavarian Obersalzberg, was idyllically removed from the stresses and strains of political and military affairs, that neither she nor they discussed or knew about the persecution and mass murder of Europe’s Jews, or the extermination of other groups, from Soviet prisoners of war to Germany’s mentally handicapped.

Yet Hitler’s inner circle, including Eva Braun, did not live exclusively at the Berghof, cut off from the events that took place in the great cities such as Munich and Berlin where they also spent much of their time. They witnessed the nationwide pogrom of November 9–10, 1938, when thousands of Jewish-owned shops were trashed by mobs of Nazi storm troopers, hundreds of synagogues set ablaze, and thirty thousand Jewish men publicly rounded up, abused, maltreated and sent off to concentration camps. They saw the signs put up on the roads leading to villages around the Obersalzberg announcing that Jews were “not wanted” in the locality. They read the newspapers, they saw the notices in town banning Jews from local amenities such as municipal libraries and swimming pools.

Though Eva left few concrete indications of her political views, some can be found in her photograph album, which included snaps of Hitler and his entourage during the tense period leading up to the outbreak of war, which she accompanied with typed captions such as: “Poland still does not want to negotiate”; or: “The Führer hears the report over the radio.” If Hitler listened to radio reports, then so too did she. There can be little doubt that Eva Braun closely followed the major events of the war, nor that she felt her fate was bound inextricably to that of her companion from the outset. “If something happens to him,” she said, as she listened in the press gallery, weeping, to Hitler’s declaration in the Reichstag on the outbreak of war that he would only take off the soldier’s uniform he now wore “after our victory, or not live through its end,” “I’ll die too.”

The war changed the relationship. Hitler spent increasing amounts of time in Berlin or, after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, at his field headquarters behind the Eastern Front. It is reasonable to suppose he told her where he was going before he launched the invasion, and why he was going to spend so much time there. Certainly he told his young secretaries, giving the lie to the later claim that he never talked politics to women. Hitler’s visits to the Berghof were now less frequent, though when the military situation allowed it, they could last for weeks or even months at a time. The atmosphere grew more depressed as the German armies suffered the disastrous defeat of Stalingrad at the beginning of 1943, and Allied bombers began to devastate German cities, including Munich, not long afterward. As Hitler increasingly withdrew from public view, Eva’s role grew more significant, and on June 25, 1943, Propaganda Minister Goebbels, whose voluminous diaries were by now intended primarily for postwar publication, began to mention her for the first time, and in sycophantically warm and admiring terms, in their pages.

Hitler’s stay at the Berghof from February to July 1944 was his last. He left only when rumors of an impending assassination attempt drew him back to Berlin. Before leaving, he made arrangements with Eva for the eventuality of his death; her response, he told Goebbels, was once more to tell him that if he died, she would kill herself. Given the fact that she had already tried to do this twice so was no stranger to the idea, and knowing that her enemies, who by now included the increasingly power-hungry Bormann, would drive her out if Hitler were no longer around, this was perhaps not so surprising. But it also clearly reflected genuine emotional identification. When the assassination attempt came on July 20, 1944, with Colonel von Stauffenberg’s bomb in Hitler’s field headquarters, Eva repeatedly tried to reach Hitler by phone in the ensuing hours of uncertainty, telling him when she eventually did get through: “I love you, may God protect you!”

In October 1944 Eva made her last will and testament, alarmed by reports of Hitler’s increasingly frail health. Leaving everything to her family and friends, the will once more made it implicitly clear that if Hitler died, from whatever cause, she would perish too. In November, as Hitler moved back to Berlin, Eva joined him in the apartment in the old Reich Chancellery, later, when constant bombardment from enemy planes and guns made life above ground too dangerous, relocating to the underground bunker where they were to end their lives.

Here she gave her full support to Hitler’s fanatical determination to fight to the end, hoping for victory in the face of overwhelming evidence that total defeat was only weeks away. When Hitler had his doctor, Karl Brandt, arrested and condemned to death for daring to send him a report detailing the catastrophic situation of medical services in the Reich, Eva stood by him, despite her previous friendship with Brandt, describing the physician’s conduct as mad and disgraceful. (Brandt managed to evade his fate in the chaos of the final weeks, only to be executed by the Allies after the war for medical crimes.)

After a brief farewell visit to her family in Munich, she returned to the bunker on March 7, 1945, a few weeks later writing to a friend that she was “happy to be near him.” She rejected all attempts to get her to persuade Hitler to leave Berlin. She not only kept up appearances herself but also insisted Hitler do so too, encouraging him to believe that the situation could still be turned around, or at least to behave as if it could. By projecting this image of undiminished will to fight on, she contributed to hundreds of thousands of deaths in the last weeks of the war.

Even if she sometimes became impatient with them, Eva Braun listened to many of Hitler’s political monologues, large numbers of which Bormann had noted down for posterity, and as his fervent admirer, with the barely formed views of a teenager, she no doubt accepted without question his racism, his anti-Semitism, his murderous hatred of his opponents, his megalomaniac belief in Germany’s mission to rule the world. Many of Hitler’s friends and associates whose education and maturity were well above her level accepted these things too. Heike Görtemaker’s meticulously researched biography disposes once and for all Hitler’s associates’ later, and often self-serving, claims that his private life, including his relationship with his companion, was entirely shut off from the larger world of Nazi politics and ideology. Thus it makes a major contribution to our understanding of the intimate world of the dictator and his entourage, and beyond this, to our judgment, both in general and in innumerable matters of detail, of the many postwar reminiscences in which they sought to justify themselves.

Pullquote: Nazi ideology portrayed women as essentially passive, modest, simple and undemanding creatures, whose role was to adore their menfolk. Eva Braun was no such woman.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review