Have Gun, Will Travel

Mini Teaser: The story of the AK-47 reads like a Stalinist myth. Whether it's true or not, the gun is a sure sign of humanity's penchant for violent solutions to conflict.

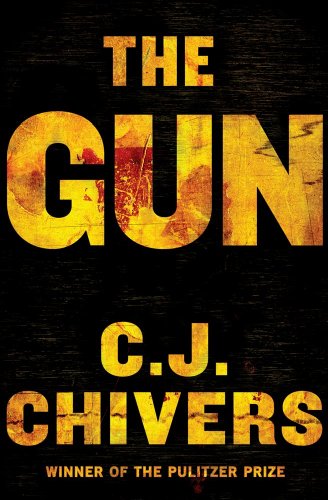

[amazon 0743270762 full]C. J. Chivers, The Gun (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 496 pp., $28.00.

IT IS not always easy to understand what makes a particular weapon iconic, or whether such an icon is really something worth having. The twentieth century has few obvious contenders. The Spitfire is perhaps the most famous because so much hung on achieving victory in the Battle of Britain. The surviving myth of the Allied David pitted against the German Goliath has an enduring, if sentimental, attraction. The B-2 Spirit stealth bomber is perhaps a modern-day equivalent, its awesome power and menace balanced by the aesthetic fascination of seeing the broad, black batwing fighter in flight.

Aircraft, of course, are fortunate. For more than a century, the evolution of modern planes, from flimsy wood and canvas biplanes to the modern fighter-bomber, has generated a persistent fascination with the air weapon; it is easy to understand why famous aircraft images are often instantly recognizable. But ask the average citizen to tell you the name of some piece of artillery or an armored car and you will get nowhere. Cans of poison gas or antipersonnel mines are not likely to end up as iconic images, and it needs little perception to understand why. The only other category of modern weapon that can match the appeal of the air is the handheld firearm. The Colt .45, the famous German Luger, the Bren gun and the Lee-Enfield rifle are not quite household names, but certainly close to the Spitfire in terms of recognition. Yet of all the handheld weapons across the world, from the age of industrial warfare on, there is one that stands out above the rest: the AK-47 assault rifle, better known as the eponymous “Kalashnikov.”

The explanation for why this simple and effective automatic weapon should end up on national flags and postage stamps is the subject of an absorbing and beautifully written new study by the American New York Times journalist and former–Marine Corps officer C. J. Chivers in a volume simply called The Gun. The book is a biography of the AK-47—in itself an acknowledgement that key weapons become effectively personified—but it is also much more. Chivers has no intention of mythologizing this rifle; the development of the gun and its subsequent worldwide use is tellingly set in a longer and wider historical context. The narrative is a critical and intelligent interrogation of a story shrouded in Soviet doublespeak. And the history of this particular weapon becomes, in an important sense, the story of the violence at the heart of the more than sixty years since the gun was first introduced.

THE TALE of the AK-47’s origins is a classic Stalinist myth. The gun, so it is claimed, was invented almost spontaneously in 1947 by a genuine proletarian, the young Senior Sergeant Mikhail Kalashnikov, an unschooled wounded veteran of the Great Patriotic War. His invention won him the coveted Hero of Socialist Labor award, and he became a model for the postwar generation of Soviet citizens educated in the sanctification of Soviet overachievers. Like the biologist Trofim Lysenko, the director of the Soviet Institute of Genetics who rejected Gregor Mendel’s theories of inheritance, Kalashnikov became a classic example of how the very ordinary Russian could rise to the heights of technical and scientific success without a whole clutch of bourgeois doctorates and diplomas. But unlike Lysenko’s wayward hostility to genetics, Kalashnikov did actually help to develop something that the Soviet state found of great and prolonged use. Whatever the deliberate aggrandizement of his reputation, the legend shrouded in half-truths, there was no doubt about the exceptional utility of a weapon that filled a niche in the battlefield market between the submachine gun and the old-fashioned repeater rifle.

Chivers is merciless in uncovering the apocryphal elements in this story, but some of it at least is true. Kalashnikov was an extraordinary social riser. Born into a peasant family, his father was denounced as a kulak during the terrible collectivization years in the Soviet Union, and he and his family were deported to Siberia. Here, the young Mikhail lived a tough and unpromising childhood with a family that eventually suffered all the trials of the Stalinist dictatorship—two brothers killed in the war, another condemned to life in a camp. But true to the quirky nature of the Soviet system, none of this actually prevented Kalashnikov from becoming a wartime engineer in 1942, following his injury as a tankman, and in the end rising to the honorary rank of lieutenant general after the success of the gun that bore his name. If you were lucky, the Soviet Union could be a land of rags to riches.

THE REST of the story needs real contextualization. Chivers starts by looking at the long history of automatic weapons, from the first machine gun designed by the famous Richard J. Gatling during the Civil War through to the semiautomatic weapons of World War II. This is a long story, and perhaps overelaborate for a history that really belongs to the second half of the twentieth century. But what it does show is the common goal of all modern war-fighting systems: a battlefield weapon that does the right thing, effectively and cheaply. The same story could be told about the search for a bomber aircraft that could actually hit and destroy important military targets rather than smother the surrounding area with high explosives or napalm. The modern fighter-bomber, the modern tank, the modern artillery piece and the modern firearm are each the product of a very long period of technical and tactical improvement to ensure above all that the armed forces got a weapon that could do the job they wanted done efficiently and at relatively low cost. For all the fuss made of the Lancaster bomber in World War II, it was a large and expensive air vehicle whose primary purpose, since it could do little else, was to flatten large parts of the enemy’s cities rather than destroy Axis military supplies, vital military-economic targets and the enemy’s battlefield capability. The B-52 did the same in Vietnam. Modern aircraft are incomparably more expensive, but they can usually deliver an effective military outcome without destroying 50 percent of an urban area or obliterating the countryside.

Such was the case with the evolution of the AK-47. It was the product of a long search for an ideal infantry weapon to replace the aging standard Russian Mosin-Nagant rifle, which dated back to before World War I. Here, Chivers makes a point seldom recognized by military historians—that a gun can sometimes be fashioned around the projectile it fires, not the other way around, as happened with the Kalash. The development of the more efficient M1943 cartridge, first produced in March 1944 (and modeled to some extent on a German advance, the 7.92 Kurz), needed less propellant and a shorter barrel but could still hit and inflict lethal damage on a battlefield target at long range. If it lacked the velocity of rifle cartridges, it made up for this by being housed in guns with a very rapid rate of automatic fire, like a machine gun but lighter, more accurate, and capable of being carried and used by just one soldier. This might seem like military nit-picking, but the potential advantages were clear enough to the Kremlin that a lengthy contest was held to create an automatic rifle to utilize the M1943 cartridge effectively. Kalashnikov and his small design team were invited to contend.

Chivers shows that the development of the AK-47 was a collective effort. Kalashnikov was a good front man, personable and well able to take care of himself in the murky world of bureaucratic politics. But the design was worked on by a team; the extent to which the critical breakthroughs in stage two of the competition in 1947, when the gun was shortened and its mechanism simplified, were really Kalashnikov’s brainchild may never be known. The design was cost-effective. It had an easy-to-make frame with a wooden stock. It was a weapon very easy to assemble and disassemble. And, above all, the gun utilized some of the energy (in the form of gases) released by the cartridge to start the automatic process which would launch the follow-on bullet. The M1943 would have no wastage of materials or energy; together the gun and bullet were cheap, light and deadly. This happy symbiosis was perhaps what secured final victory for Kalashnikov’s team in January 1948.

Later that year, production began in factories at Izhevsk of a gun now designated Avtomat Kalashnikova–47. The “47” marked the date the gun was developed. It took another two years to refine and improve the design before the Red Army finally made it standard issue. Chivers speculates that German weapons designer Hugo Schmeisser, who created the first genuine assault rifle (the German Maschinenkarabiner 42) during World War II, might have been dragooned into helping with the design. Whatever the truth, Kalashnikov was the name on the product, but the gun itself was, as Chivers describes it, a “people’s gun.”

Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review