The Mind of an Israeli Maverick

Mini Teaser: Benny Morris reviews Gilad Sharon's biography of his father, Ariel Sharon.

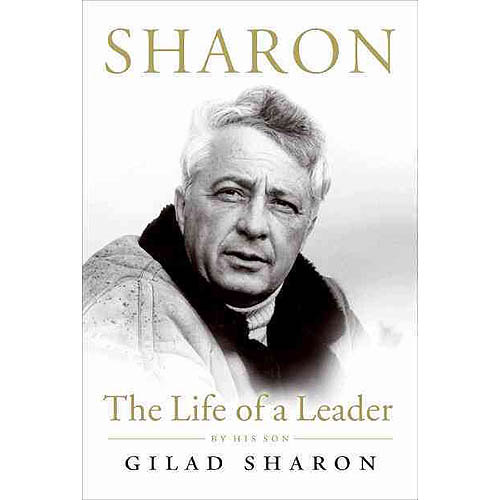

Gilad Sharon, Sharon: The Life of a Leader (New York: Harper, 2011), 640 pp., $29.99.

In surveying the personality and career of Ariel Sharon, Israel's ninth prime minister and a man of controversy throughout his life, a good place to start might be a 1973 Egyptian intelligence assessment of the man, who fought and beat the Egyptians in the wars of 1956, 1967 and 1973. It read:

Characteristics: Full-bodied, silvery hair, very calm, confident, enamored with the act of self-sacrifice, a talented officer, stubborn, dynamic, brave, in love with the Paratroops and the Special Forces, a believer in the element of surprise, prone toward violence, loves to learn and to know.

That report, produced by Sharon’s adversaries, demonstrates the respect he has acquired as a man of conviction and character. But he has also been reviled at times during his career as he put his remarkable stamp upon the history of Israel. The February 1955 raid he led against the Egyptian military in the Gaza Strip precipitated Egypt's turn toward the Soviet Union and the acquisition of Soviet armaments, among the chief causes of the Sinai-Suez war the following year. As Israel's defense minister in 1982, he orchestrated the Israeli Defense Forces invasion of southern Lebanon. As prime minister in 2002, he launched the IDF offensive that crushed the second Palestinian intifada. And in 2005, he uprooted the Israeli settlements and pulled the IDF out of the Gaza Strip.

Now Sharon lies in a stroke-induced coma that ended his career nearly six years ago. But it is not surprising, given his impact, that there would be now a spate of biographies in the works. This, by his son Gilad, is the first. Probably most biographies of fathers written by their children are hagiographic, and this is no exception. But the book is not without value. It presents a moving story of Sharon's upbringing in harsh circumstances and a somewhat problematic family in a cooperative settlement in Mandate Palestine, with Arab marauders and thieves preying constantly on Jewish villagers. Sharon’s Russian-born parents seem to have indulged in a deliberate bad-neighbor policy, and the family suffered social ostracism. Within the family circle, they rarely displayed affection. The ostracism and the absence of familial warmth, says Gilad, explain Sharon’s lifelong search for "emotional tenderness.” Indeed, Sharon grew up an outsider and a maverick and remained so in his military and political careers. His mother slept with a pistol under her pillow until she was "around eighty" and stored a "heavy club" under her bed until her death. This may help explain Sharon’s later conviction that if force doesn't solve a problem, employ greater force.

Gilad sheds light on softer aspects of Sharon's character: "I never once saw him remain seated when a woman entered a room or came to the table.” Unusually among Israeli leaders, he was apparently faithful to his two wives, Margalit and her sister Lilly (whom he married after Margalit's death in 1962). He was much loved by his staff and lived a frugal life (except when it came to lobsters and foie gras).

An account of Sharon's military career reads like a history of Israel’s first decades. As a young lieutenant, he fought in the first battle of Latrun in May 1948 as the Haganah tried to break the siege of Jerusalem. In 1953, he was commissioned to establish Unit 101, which spearheaded the IDF's reprisals against Egypt and Jordan following Arab terrorist attacks on Israeli border villagers. Later, when Unit 101 was merged with the largely unemployed (and barely competent) paratroop battalion, Sharon was given overall command. By 1956, he commanded the IDF's paratroops, by then a brigade, which thrust across the Sinai Peninsula in the October-November 1956 Sinai/Suez War. In 1967, Sharon commanded one of the three armored divisional task forces that thrashed the Egyptians in Sinai. Sharon won accolades for his masterful orchestration of the capture of enemy positions. And in 1973 Sharon commanded the division that turned the tide and crossed the Suez Canal westward, initiating the encirclement of the Egyptian Third Army, which was stranded on the Israeli side of the canal, surrounded and starved of ammunition, food and fuel. Its destruction or surrender was certain. But the threat of Soviet intervention and American arm-twisting in Jerusalem saved it.

Throughout his military career, Sharon was an inventive if sometimes insubordinate maverick whose battlefield successes triggered the envy of lesser officers. And he seemed to regard most of his superiors as undeserving and sometimes wrongheaded mediocrities. Gilad Sharon's descriptions of his father's relations with successive IDF chiefs of staff—Chaim Bar-Lev (1968-1972) and David Elazar (1972-1974)—are suffused with the contempt no doubt passed on by his father. Bar-Lev, for example, sired the "Bar-Lev Line,” a defensive concept and chain of forts that Sharon had opposed. It collapsed under Egyptian assault like a house of cards in October 1973. Elazar was responsible for the IDF's failure to foresee and then effectively counter the Egyptian-Syrian Yom Kippur assault.

In recounting his father's exploits in October 1973 and the machinations of his colleagues and superiors, Gilad Sharon almost goes so far as to accuse these other officers of trying to foil his cross-canal campaign just to spite him. Gilad writes that preventing Sharon from winning glory was more important to them than beating the Egyptians.

I believe Gilad is mistaken in his implied allegation. The general staff opted for the swing southwards to the Gulf of Suez not because it was led by generals other than Sharon but because the route was shorter, less heavily populated and less encumbered with water obstacles than any sweep northward to the Mediterranean coast.

Sharon demonstrated decisiveness in both his political and military careers. In the 1970s, he put together the Likud, combining a number of right-wing and centrist parties, thus paving the way for Menachem Begin's revolutionary 1977 electoral victory. And in the first years of the millenium he broke away from the Likud and founded the centrist, and victorious, Kadima Party.

In the IDF, his soldiers followed him through hell and high water, although there were allegations that he was insufficiently sensitive to Israeli loss of life. His troops’ loyalty stemmed in part from his courage and coolheadedness in battle. Reservists trapped near the Suez Canal during the October 1973 War recall that Sharon's voice on the radio network always steadied frayed nerves. He inculcated what was to become a core principle in the IDF—never leave wounded soldiers on the battlefield—as a result, perhaps, of his sense of abandonment when, badly wounded, he was left on the fields of Latrun in May 1948.

Although not without virtues, the book is poorly researched and occasionally dull. Gilad Sharon did not consult Israel's voluminous military records and state papers. But it offers arresting, occasionally illuminating political anecdotes. Sharon's relations with the Jordanian leadership, including King Hussein, were remarkable. The Jordanians didn’t trust Benjamin Netanyahu during his 1996-1999 premiership, but they admired Sharon. Gilad remarks that "as far as I know, my father was the only world leader to go and visit the dying king [Hussein] in the Mayo clinic.”

Occasionally, the biography offers up sweeping historical reflections, although for the most part it isn’t clear whether they are Gilad's alone or mirror his father’s views. For example, the book argues that "the anti-Israeli policies in Europe" can be attributed in part to the massive postwar Muslim immigration to the Continent:

The modern wave of immigration is threatening—without a single battle—to achieve what the Moors attempted via Spain in the eighth century and what the Ottomans longed for from the fifteenth century to the seventeenth century, until, in 1683, they were finally stopped at the gates of Vienna.

Gilad, perhaps reflecting his father's multilayered thinking, sees "a degree of historic justice” in Europe’s colonial powers now receiving masses of people from the regions they once pillaged.

Perhaps the most interesting part of this book is the author's recollections of his father's views about various leaders. Of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, Gilad Sharon writes: "Even a polygraph would have had a hard time pinning him down; after all, the device requires some utterance of truth so that it can be compared to the lies."

But Gilad, no doubt reflecting his father, is no more forgiving with Israel's leaders. Of Moshe Dayan, the legendary general, defense minister and foreign minister, Sharon said (according to Gilad): "He was brave to the point of insanity" on the battlefield, but in public life he was “a coward.” He was "terrified" of Ben-Gurion, the man who raised him to the purple.

Gilad adds that in the 1960s, when Dayan entered politics, Ben-Gurion asked Sharon what he thought of Dayan as an agriculture minister.

Sharon: "He can be an excellent agriculture minister, but never prime minister."

Ben-Gurion: "Why?"

Sharon: "Because he is never willing to take responsibility."

The book is larded with contempt for Netanyahu, whom Sharon regarded as a weakling and thoroughly untrustworthy. Gilad relates that after his 1996 election as prime minister, Netanyahu strongly hinted that he would appoint Sharon defense minister. Sharon, according to Gilad, predicted: "He won't abide by a single thing he said." A few days later, according to Gilad, Sharon told Netanyahu: "A liar you were and a liar you have remained."

Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review