Revolutionaries Inside the Capitol

Mini Teaser: America's founding is a gripping tale of rivalry, treachery and ultimately triumph. The divisive politics of today are nothing compared to those now celebrated on the cliffs of Mt. Rushmore.

THE WAR joined by Yankee minutemen in April 1775 unfolds mostly in the background of Rakove’s briskly written narrative. It is nevertheless a transformative experience for officers, enlisted men and sideline patriots alike. Even before independence is declared, its repercussions are hotly debated. So are the rights of individuals and the meaning of liberty in a land where approximately one in eight Americans is owned by another American. The author shrewdly assesses George Washington, man and general, as much closer in disposition to George Marshall than George Patton. His commander in chief is a patrician taught by hard experience to value the New England rabble, and a pragmatist who learns most from his mistakes.

In Rakove’s Revolution, old attitudes and allegiances are equally expendable. So Washington comes to rethink his conventional—for a Virginia planter—views about race, complimenting the African-American poetess Phillis Wheatley on her verses, and accepting thousands of black patriots into his ranks. A gouty George Mason incorporates a declaration of rights into Virginia’s new constitution. Young Jack Laurens, scion of one of South Carolina’s most prominent slaveholding families, offers to raise and equip an army of three thousand slaves, the first step to emancipation.

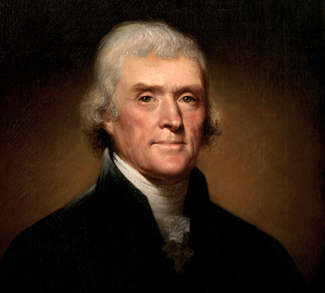

Then there is the legal revolution waged by Thomas Jefferson to diminish the power of a landholding oligarchy to which he belongs. Paradoxical as ever, this humanitarian-looking-down-on-humanity-from-his-Virginia-mountaintop hatches a scheme to broaden educational opportunities through a state-enforced meritocracy. Rakove’s careful rereading of Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia leads him to harshly condemn the author’s impressionistic speculation about the black man, an analytical “mess” unbecoming a natural scientist, let alone a professed friend of liberty. Yet he credits Jefferson with at least trying to confront the issue of slavery, a conundrum that would bedevil his descendents and tarnish his posthumous reputation. With similar empathy Rakove depicts the dance of the moderates, men like John Dickinson and Robert Morris, who are propelled against their wishes into a world of painful, unavoidable choices between some form of accommodation within the empire or a brutal act of matricide.

IN TRUTH the most radical actions in Revolutionaries transpire after the war, as the embryonic nation moves with crablike indirection toward self-government. Rakove is at his best explaining the Madisonian agenda, profoundly hostile toward state sovereignty, that is put forward at the Constitutional Convention; the emergence of public opinion, first in legitimizing the new regime, and later in checking its alleged excesses; and the rapid, unforeseen centralization of authority in the executive. Alexander Hamilton, the psychologist, helps goad a reluctant Washington into serving as the nation’s first president. Thereafter, Hamilton, the financial visionary, establishes the public credit through tariffs and taxes, consolidating power through the assumption of state debts by the new federal government and the creation of a national bank. Jefferson, quick to smell a royalist rat, accuses his cabinet rival of betraying the Revolution by cozying up to the harlot England. As the bitter controversies roused by the Hamiltonian program polarize regions and classes, Jefferson and Hamilton serve as most reluctant midwives at the birth of American party politics.

[amazon 0195039149 full]INEVITABLY, PARTS of Rakove’s story overlap with Empire of Liberty, Gordon Wood’s magisterial portrait of Young America (1789–1815) as part of the Oxford History of the United States series; no more so than in the growing class struggles animating the new Republic. The passions kindled on this side of the Atlantic by the French Revolution reinforce divisions first opened by domestic disputes. One Boston audience, steeped in the town’s tradition of political mayhem and offended by the comic portrayal of a French character in a British play, vented its wrath by demolishing the theater.

Following in Washington’s footsteps, John Adams was forced to navigate the same treacherous waters of official neutrality and popular clamor. Devoid of his predecessor’s charisma, the squat, unmartial Adams, contemptuous of politics and saddled with a turncoat cabinet, nevertheless secured an honorable peace for his badly divided nation in 1800 after the so-called Quasi-War with France. His reward for this was involuntary retirement at the polls, and prolonged exile to his hometown of Quincy, Massachusetts. There the ex-president, an all-too-human compound of self-sacrifice and self-pity, was left to brood upon public ingratitude. His electoral sentence was only somewhat leavened by repeated opportunities to indulge himself in the favorite Adams pastime of saying I told you so. To Wood’s credit, this most easily caricatured of America’s Founders remains stubbornly true to life. The same can be said of his contemporaries. Equally adept at the large canvas and the thumbnail sketch, the author enlivens his narrative with revealing factoids, as welcome as nut clusters in a box of chocolate creams.

Already a nation of nations, fully 40 percent of white Americans in the 1790 census traced their ancestry to somewhere other than England. Their explosive fertility prompted one early demographer to forecast that by the middle of the twentieth century the United States would contain 860 million inhabitants.

Between 1790 and 1820 the individual consumption of distilled spirits doubled, to five gallons a year, or nearly three times the amount disappearing down the throats of twenty-first-century Americans.

And my personal favorite: Columbia professor and future congressman Samuel Mitchill proposed to rechristen the United States of America, Fredonia.

Failing to affix this Grouchoesque name to the young confederation, Mitchill wrung his hands over the hustling materialism which defined his countrymen long before the CNBC Nation. “From one end of the continent to the other,” he complained in 1800, “the universal roar is Commerce! Commerce! at all events, Commerce!” A dissenting view was registered, barely, by Alexander Hamilton. On the night before he died in a duel with ambitious, amoral Aaron Burr, a gloomy Hamilton confessed that he could see “no relief to our real Disease; which is DEMOCRACY.” Shortly thereafter, his Federalist Party became one of history’s few political organizations to die of consistency.

If there is an overriding theme to this eight-hundred-page historical smorgasbord, it is the pervasive egalitarian instinct that helped drive the Revolution, and shaped American politics, long before Andrew Jackson built a fabled political career on Us versus Them. If there is one individual who defines the period’s optimism, raw energy and hypocrisies, it is Thomas Jefferson. To call him the political champion of the unprivileged-but-striving “middling sorts” who crowd out their presumed betters in a land defined by social mobility is not to overlook the contradictions which have frustrated countless biographers.

In theory (and no man had more) a radical utopian, Jefferson as president adopted the utterly sensible position that “no more good must be attempted than the people will bear.” At the same time, his facility for imperishable prose was equaled by a verbal extremism that will prompt even admirers to scratch their heads in bewilderment. During the Washington administration, Jefferson classed Hamilton’s federally chartered bank as “an act of treason” against the states. Six years later, as vice president under Adams, Jefferson weighed the idea of amending the Constitution to deprive the federal government of the power to borrow. His theory that the earth belongs to the living, not the dead, was interpreted to mean that all laws, debts and constitutions should expire with each generation, or roughly every nineteen years.

An unconservative Conservative, Jefferson’s nationalism took ever-odder forms. In a hostile world, a cheese-paring President Jefferson all but disbanded America’s navy, slashed the overall military budget by 50 percent, and reduced the new nation’s overseas presence to a trio of neglected missions in London, Paris and Madrid. By contrast, when his strict-constructionist principles clashed with his continental aspirations, Jefferson and his followers proved as adept at employing the “necessary and proper” clause of the Constitution to buy Louisiana as Hamilton had been in justifying a national bank. For which history, not to mention virtually everyone living west of Vincennes, Indiana, duly honors the third president.

Though clearly sympathetic to the Jeffersonian impulse, Wood doesn’t shy away from presenting the Sage of Monticello in a less flattering light. His empathetic gift for writing from the inside out helps modern readers to understand the paranoia behind the 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts, a shocking breech of fundamental liberties, as well as Jefferson’s subsequent war on the Federalist-tinged judiciary. Particularly notable are chapters examining the origins of judicial review, the resuscitation of slavery and the separatist impulse fed by a successful slave rebellion on the island of Haiti, and the restless reforming spirit which gave rise to numberless schools, benevolent associations and missionary societies.

COMPARED TO the revolutionary generation, the Jeffersonian Republic was younger, more mobile, more evangelical and more promiscuous (premarital pregnancies attained levels unequaled until the swinging 1960s). It also was decidedly more violent. On learning that war had been declared against Great Britain in June 1812, a Baltimore mob displayed its patriotism by demolishing a Federalist newspaper office. Another, equally frenzied crowd attacked prominent Federalists jailed for their own protection, killing one revolutionary general and permanently crippling Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, Washington’s eulogist and the father of Robert E. Lee. Faithful to his minimalist principles, President James Madison suffered repeated military embarrassments, culminating in the British sacking of Washington in August 1814. But no one went to jail for criticizing the president or his conduct of the war. This is why to libertarians then and since Madison is seen as a supremely constitutional wartime leader, the UnLincoln. His contemporaries were sufficiently impressed to give Madison’s name to fifty-seven towns and counties, more than any president on Mount Rushmore.

Pullquote: If there is an overriding theme, it is the pervasive egalitarian instinct that shaped American politics long before Andrew Jackson built a fabled political career on Us versus Them.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review