The Fallacy of Human Freedom

Mini Teaser: Faith in progress and the perfectibility of human nature are at the center of Western thought. What if this faith is misplaced?

John Gray, The Silence of Animals: On Progress and Other Modern Myths (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), 288 pp., $26.00.

JEAN-JACQUES Rousseau famously lamented, “Man is born to be free—and is everywhere in chains!” To which Alexander Herzen, a nineteenth-century Russian journalist and thinker, replied, in a dialogue he concocted between a believer in human freedom and a skeptic, “Fish are born to fly—but everywhere they swim!” In Herzen’s dialogue, the skeptic offers plenty of evidence for his theory that fish are born to fly: fish skeletons, after all, show extremities with the potential to develop into legs and wings; and there are of course so-called flying fish, which proves a capacity to fly in certain circumstances. Having presented his evidence, the skeptic asks the believer why he doesn’t demand from Rousseau a similar justification for his statement that man must be free, given that he seems to be always in chains. “Why,” he asks, “does everything else exist as it ought to exist, whereas with man, it is the opposite?”

This intriguing exchange was pulled from Herzen’s writings by John Gray, the acclaimed British philosopher and academic, in his latest book, The Silence of Animals: On Progress and Other Modern Myths. As the title suggests, Gray doesn’t hold with that dialogue’s earnest believer in freedom—though he has nothing against freedom. He casts his lot with the skeptic because he doesn’t believe freedom represents the culmination of mankind’s earthly journey. “The overthrow of the ancien régime in France, the Tsars in Russia, the Shah of Iran, Saddam in Iraq and Mubarak in Egypt may have produced benefits for many people,” writes Gray, “but increased freedom was not among them. Mass killing, attacks on minorities, torture on a larger scale, another kind of tyranny, often more cruel than the one that was overthrown—these have been the results. To think of humans as freedom-loving, you must be ready to view nearly all of history as a mistake.”

Such thinking puts Gray severely at odds with the predominant sentiment of modern Western man—indeed, essentially with the foundation of Western thought since at least the French Encyclopedists of the mid-eighteenth century, who paved the way for the transformation of France between 1715 and 1789. These romantics—Diderot, Baron d’Holbach, Helvétius and Voltaire, among others—harbored ultimate confidence that reason would triumph over prejudice, that knowledge would prevail over ignorance, that “progress” would lift mankind to ever-higher levels of consciousness and purity. In short, they foresaw an ongoing transformation of human nature for the good.

The noted British historian J. B. Bury (1861–1927) captured the power of this intellectual development when he wrote, “This doctrine of the possibility of indefinitely moulding the characters of men by laws and institutions . . . laid a foundation on which the theory of the perfectibility of humanity could be raised. It marked, therefore, an important stage in the development of the doctrine of Progress.”

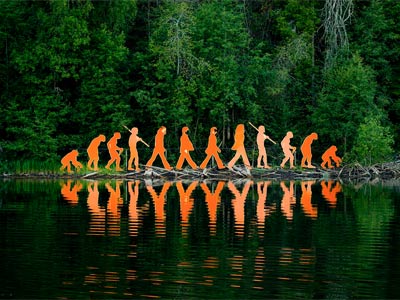

We must pause here over this doctrine of progress. It may be the most powerful idea ever conceived in Western thought—emphasizing Western thought because the idea has had little resonance in other cultures or civilizations. It is the thesis that mankind has advanced slowly but inexorably over the centuries from a state of cultural backwardness, blindness and folly to ever more elevated stages of enlightenment and civilization—and that this human progression will continue indefinitely into the future. “No single idea,” wrote the American intellectual Robert Nisbet in 1980, “has been more important than, perhaps as important as, the idea of progress in Western civilization.” The U.S. historian Charles A. Beard once wrote that the emergence of the progress idea constituted “a discovery as important as the human mind has ever made, with implications for mankind that almost transcend imagination.” And Bury, who wrote a book on the subject, called it “the great transforming conception, which enables history to define her scope.”

Gray rejects it utterly. In doing so, he rejects all of modern liberal humanism. “The evidence of science and history,” he writes, “is that humans are only ever partly and intermittently rational, but for modern humanists the solution is simple: human beings must in future be more reasonable. These enthusiasts for reason have not noticed that the idea that humans may one day be more rational requires a greater leap of faith than anything in religion.” In an earlier work, Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals, he was more blunt: “Outside of science, progress is simply a myth.”

GRAY’S REJECTION of progress has powerful implications, and his book is an attempt to grapple with many of them. We shall grapple with them as well here, but first a look at Gray himself is in order. He was born into a working-class family in 1948 in South Shields, England, and studied at Oxford. He gravitated early to an academic life, teaching eventually at Oxford and the London School of Economics. He retired from the LSE in 2008 after a long career there. Gray has produced more than twenty books demonstrating an expansive intellectual range, a penchant for controversy, acuity of analysis and a certain political clairvoyance.

He rejected, for example, Francis Fukuyama’s heralded “End of History” thesis—that Western liberal democracy represents the final form of human governance—when it appeared in this magazine in 1989. History, it turned out, lingered long enough to prove Gray right and Fukuyama wrong. Similarly, Gray’s 1998 book, False Dawn: The Delusions of Global Capitalism, predicted that the global economic system, then lauded as a powerful new reality, would fracture under its own weight. The reviews were almost universally negative—until Russia defaulted on its debt, “and the phones started ringing,” as he recalled in a recent interview with writer John Preston. When many Western thinkers viewed post-Soviet Russia as inevitably moving toward Western-style democracy, Gray rejected that notion based on seventy years of Bolshevism and Russia’s pre-Soviet history. Again, events proved him correct.

Though often stark in his opinions, Gray is not an ideologue. He has shifted his views of contemporary politics in response to unfolding events and developments. As a young man, he was a Labour Party stalwart but gravitated to Margaret Thatcher’s politics after he concluded, in the late 1970s, that Labour had succumbed to “absurdist leftism.” In the late 1980s, disenchanted with the “hubristic triumphalism” of the Tories, he returned to Labour. But he resolutely opposed the Iraq invasion led by America’s George W. Bush and Britain’s Tony Blair, and today he pronounces himself to be a steadfast Euroskeptic.

Though for decades his reputation was confined largely to intellectual circles, Gray’s public profile rose significantly with the 2002 publication of Straw Dogs, which sold impressively and brought him much wider acclaim than he had known before. The book was a concerted and extensive assault on the idea of progress and its philosophical offspring, secular humanism. The Silence of Animals is in many ways a sequel, plowing much the same philosophical ground but expanding the cultivation into contiguous territory mostly related to how mankind—and individual humans—might successfully grapple with the loss of both metaphysical religion of yesteryear and today’s secular humanism. The fundamentals of Gray’s critique of progress are firmly established in both books and can be enumerated in summary.

First, the idea of progress is merely a secular religion, and not a particularly meaningful one at that. “Today,” writes Gray in Straw Dogs, “liberal humanism has the pervasive power that was once possessed by revealed religion. Humanists like to think they have a rational view of the world; but their core belief in progress is a superstition, further from the truth about the human animal than any of the world’s religions.”

Second, the underlying problem with this humanist impulse is that it is based upon an entirely false view of human nature—which, contrary to the humanist insistence that it is malleable, is immutable and impervious to environmental forces. Indeed, it is the only constant in politics and history. Of course, progress in scientific inquiry and in resulting human comfort is a fact of life, worth recognition and applause. But it does not change the nature of man, any more than it changes the nature of dogs or birds. “Technical progress,” writes Gray, again in Straw Dogs, “leaves only one problem unsolved: the frailty of human nature. Unfortunately that problem is insoluble.”

That’s because, third, the underlying nature of humans is bred into the species, just as the traits of all other animals are. The most basic trait is the instinct for survival, which is placed on hold when humans are able to live under a veneer of civilization. But it is never far from the surface. In The Silence of Animals, Gray discusses the writings of Curzio Malaparte, a man of letters and action who found himself in Naples in 1944, shortly after the liberation. There he witnessed a struggle for life that was gruesome and searing. “It is a humiliating, horrible thing, a shameful necessity, a fight for life,” wrote Malaparte. “Only for life. Only to save one’s skin.” Gray elaborates:

Pullquote: Progress is the idea that mankind has advanced slowly but inexorably from a state of cultural backwardness, blindness and folly to ever more elevated stages of enlightenment. Gray rejects it utterly.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review