The Great White House Rating Game

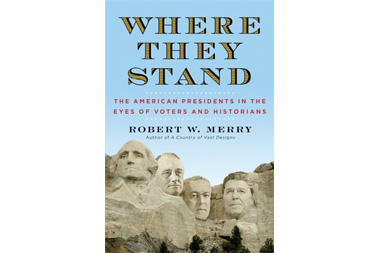

Mini Teaser: Robert Merry’s new book explores the academic impulse to assess the presidents—but with a twist. He melds contemporaneous judgments of the electorate with academic polls to yield an engaging history.

Merry’s fundamental approach to presidential achievement is a “referendum” touchstone. The judgment of scholars and journalists, burdened by political and ideological commitments, attempting to burrow from the present into a distant past, he asserts, is less useful than the contemporary verdict of the people themselves. Reprimanding journalists who cover election campaigns by emphasizing tactics and ephemeral day-to-day events, he believes that the electorate takes a broad view. Presidential elections, he argues, are usually decided on the basis of approval or disapproval of the incumbent’s performance. A president who is reelected thus has a presumptive claim to a superior ranking. A two-term president whose designated party successor wins election has to be considered for greatness. Still, the twelve who have met this criterion—Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson, Lincoln, Grant, McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, Coolidge, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan—will strike most of us as a mixed lot.

IN THE chapters that follow, Merry rakes over the reputations of numerous presidents, giving us his own take on what the historians got right and unhesitatingly telling us when he thinks they erred.

Take the conventional view of James Madison, customarily revered as the father of the Constitution but dismissed as at most a mediocre chief executive incapable of exerting the strong presidential leadership exemplified by his friend and predecessor Thomas Jefferson. In large measure, Merry tells us, Madison was the victim of a hit job by Henry Adams—great-grandson of John Adams and grandson of John Quincy Adams—in his magisterial History of the United States of America During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Madison, as Merry sees him, was a resolute defender of American rights against British encroachment on the high seas and a determined foe of British designs to seize control of the northwestern United States. He was a principled Jeffersonian liberal who waged the War of 1812 without persecuting its opponents and a flexible pragmatist willing to back those elements of the opposition agenda (such as a national bank and a mild protective tariff) he thought the country needed.

Or how about Ulysses S. Grant, rated dead last alongside Warren G. Harding in Schlesinger Sr.’s 1948 survey but the beneficiary of a “miniboomlet” in more recent years? (The 2009 C-SPAN survey placed him twenty-third, squarely in the middling category.) Merry attributes this to a current trend in academic liberalism that lauds rather than condemns Radical Reconstruction and points to recent favorable biographies. Presidential surveys do in fact reflect changing fashions in academic liberalism, and Grant is an excellent case study of a process worth a bit more attention.

For at least three-quarters of a century, American populism and progressivism bought into fundamental intellectual and cultural compromises that reunited the nation after the Civil War. In return for Southern acquiescence in the maintenance of the Union and the canonization of Abraham Lincoln, a Northern intelligentsia accepted the Confederacy as an honorable, if misguided, insurgency, accepted the proposition that blacks were not and might never be ready for full citizenship, and conceded that Radical Reconstruction was an especially odious form of Northern oppression. The martyred Lincoln was off limits, but Grant was a convenient scapegoat. As commander of the Union forces, he had enabled Sherman’s march through Georgia and compelled Lee’s surrender. As president, he was the chief enforcer of Reconstruction and suppressor of the Ku Klux Klan.

Northern intellectuals could buy into these complaints with few qualms while detesting the rampant industrialization of America during the Gilded Age and the rise of a crass new elite concerned only with money and power. Here also, one finds the hand of that displaced patrician Henry Adams holding a bloody dagger: “The progress of evolution from President Washington to President Grant was alone evidence enough to upset Darwin.”

This worldview in which Grant’s reputation was caught up changed slowly. It was not until the 1960s that major cracks began to appear as liberal intellectuals committed themselves more fully to civil rights and a revolutionary change in a racist Southern society. It became possible to see the Grant presidency as a mixed achievement—its first term was marked by an economic prosperity that grew out of the industrial surge the Henry Adamses of the world found distasteful; its second term was marred by a financial crash and the emergence of scandals Grant handled poorly. To probably a majority of Americans, however, Grant remained a hero who likely could have had a third term had he chosen to run for one.

Merry concludes, fairly enough, that a judicious evaluation of Grant’s successes and failures would merit an average standing. He also underscores another, more urgent motivation for Grant’srise when he quotes Princeton historian Sean Wilentz’s defense of the general as “one of the great presidents of his era, and possibly one of the greatest in all American history.” Professor Wilentz was contesting a suggestion that Grant should be evicted from the fifty-dollar bill and replaced by Ronald Reagan.

Grant’s one-time partner at the bottom of the heap, Warren G. Harding, also gets a case for a qualified upgrade. Some of his appointments were corrupt or mediocre, but others were outstanding. Inheriting a severe recession from Woodrow Wilson, he allowed the economy to heal itself and was presiding over a strong recovery at the time of his death in 1923. It is widely conceded that he was a popular chief executive. Only afterwards did the Teapot Dome scandal and other examples of bad behavior by his appointees besmirch his reputation.

Merry mentions in passing Harding’s alleged affair with Nan Britton, who claimed after his death that Harding was the father of a daughter they had conceived during a tryst in a White House broom closet. He also tells us that Harding had one long-running extramarital affair before he became president, but he seems to have broken that off prior to his nomination. (His backers financed a leisurely trip to Japan for the lady in question, Carrie Phillips; it took her out of the country for the duration of the 1920 campaign.) As for Britton, historians have failed to discover any tangible evidence for her claim, which, even if true, would make Harding seem positively monogamous compared to John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson or Bill Clinton. No matter, Merry concludes. Fairly or otherwise, “Harding’s position in history probably won’t change anytime soon, notwithstanding his high regard with his constituency during his presidency.”

The case for Calvin Coolidge’s consistently below-average evaluation, the author believes, is very weak. “He presided over peace, prosperity, and domestic tranquility for nearly six years, and he effectively cleaned up the scandal bequeathed to him by Harding.” Coolidge, he suggests, was a victim of his own laconic personality and his rejection of presidential activism. Recent polls may reflect Merry’s sense that “Silent Cal” has been underrated; the Wall Street Journal (2005) and C-SPAN (2009) give him an average standing.

WHO, THEN, were the real failures? Merry writes at some length about Herbert Hoover, conceding his many virtues and talents but stoutly rejecting “average” evaluations in five of the seven surveys this book spotlights. He believes Hoover helped bring on the Great Depression by signing the Smoot-Hawley tariff, made it worse with stiff tax increases and was overwhelmed by the tidal waves of bank failures that brought the economy crashing down. Much of the personal vilification he received was unfair, but “American presidential politics wasn’t designed to be fair. . . . In times of turmoil the people can become harsh and unfeeling in their sentiments.” Their contemporary judgment, “brutal and insensitive as it was, captures the man’s performance more accurately than those academic surveys.”

Lincoln’s two predecessors, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan, widely classified in the failure category, seem to Merry easy calls. Both men, through a combination of inactivity and deviousness, facilitated the outbreak of the Civil War. Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, long was a beneficiary of the post–Civil War worldview and considered a victim of persecution by vindictive Radical Republicans. Merry thinks he probably belongs in the failure category, “in part, it can be argued, because he was on the wrong side of the issues but also because he lost control of the country he was supposed to lead.”

Most surprisingly, Merry suggests serious consideration of Woodrow Wilson, an almost universal “near-great” pick, for a “failure” designation. His argument bypasses Wilson’s impressive progressive accomplishments on the domestic scene and focuses on his diplomacy, which he finds seriously flawed by a sanctimonious self-righteousness: Wilson took the United States into World War I with a faulty rationale, then refused to compromise on an impractical peace settlement. (He finds a similar pattern in the presidency of George W. Bush.)

In general, the author believes foreign policy must focus on the world as it is and advocates the pursuit of national self-interest, even if (as with James K. Polk or William McKinley) it leads into naked imperialism. Who today would seriously propose the return of the southwestern United States to Mexico, or national independence for Hawaii or Puerto Rico?

Pullquote: Nineteen men have served more than one term as president. Their collective experience demonstrates that it is very difficult to negotiate more than four years in the office without significant challenges.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review