The Peculiar Life of Joseph Kennedy

Mini Teaser: From his mercurial personality to his delusions of aptitude in the political realm to his catastrophic diplomatic appointment, a new book provides a thorough account of Kennedy’s life and all of its many highs and lows.

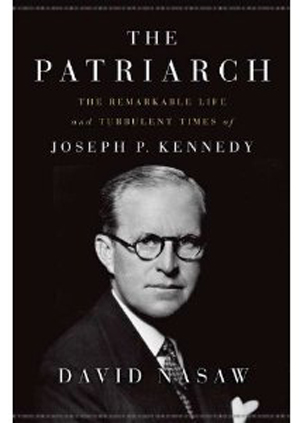

David Nasaw, The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy (New York: Penguin, 2012), 896 pp., $40.00.

THE PATRIARCH is a thorough and balanced biography that illuminates American public policy from the time of Herbert Hoover to the brief era dominated by the subject’s sons. David Nasaw, an accomplished writer, explores all of the controversial high points of Joseph Kennedy’s career meticulously, and the record is usefully set straight in many places. For the most part, the narrative is absorbing.

THE PATRIARCH is a thorough and balanced biography that illuminates American public policy from the time of Herbert Hoover to the brief era dominated by the subject’s sons. David Nasaw, an accomplished writer, explores all of the controversial high points of Joseph Kennedy’s career meticulously, and the record is usefully set straight in many places. For the most part, the narrative is absorbing.

It is well-known that Kennedy’s father and father-in-law were prominent Irish Boston figures. It is less widely known that his father, Patrick J. Kennedy, a prosperous financier, gave him an upbringing similar to what upper-middle-class Protestant East Coast families generally provided, including Boston Latin School and Harvard. Joseph Kennedy made no bones of the fact that he did not see it as his role to fight “for the British” during World War I, although he seems to have been too pugnacious a character to have believed that the United States should accept passively the German submarine sinkings of American merchant ships on the high seas. He was no pacifist, as he amply demonstrated after Pearl Harbor, and was certainly not a coward. But Kennedy used political connections to obtain a draft-exempt position in the ship-building industry after America’s entry into the Great War.

After the war, Kennedy joined a Boston merchant bank, Hayden Stone, and largely fulfilled his early ambition of cracking the Boston Brahmin financial establishment. Previously, he had been head of the Columbia Trust Bank, where his father was a director and substantial shareholder. He took this company over as almost a private bank for his stock and investment plunging at Hayden Stone. Kennedy proved a preternaturally agile investor and was almost always successful in generating gains, yet not always with complete probity. Though well established at Hayden Stone, Kennedy saw that he would never be entirely accepted. As the Roaring Twenties began in earnest on Wall Street and across the land, he shifted his sights to the immensely larger New York financial market.

Kennedy soon saw that motion pictures were a growth industry, chronically mismanaged by fly-by-night impresarios who knew nothing of administrative economies, whatever their talents at cinematic artistry and marketing. It also was a glamorous industry. He set out to achieve fame and fortune and accomplished no less. He began with film distribution in New England but quickly moved on to industry-wide arrangements and production. “Joseph P. Kennedy Presents” became a familiar tag on film credits, and Kennedy helped amalgamate several film houses in the manner of new industries that consolidate swiftly.

Nasaw estimates that Kennedy quintupled his net worth between 1926 and 1929—to perhaps $30 million in today’s money. Using his own trust company to make loans to himself (a bold but perfectly legal move), Kennedy bought a growing number of movie theaters and soon took control of the Film Booking Offices of America, Keith-Albee-Orpheum, Pathé Films and First National Corporation. He also conducted extensive negotiations with David Sarnoff of Radio Corporation of America. Then he withdrew from them profitably as they consolidated into Radio Keith Orpheum (RKO).

Despite his ostentatious Roman Catholicism, Kennedy was proud of his extensive sex life and his many attractive companions—including, over decades, legions of assistants, secretaries, masseuses and even young female golf caddies. But in Hollywood, he was able to fish greedily in the pool of starlets and aspirants to stardom. Here Nasaw strays into the swirling waters of surmise and mind reading. He assumes Kennedy’s Catholicism actually enabled him to commit such egregious serial infidelities against the mother of his nine children. Nasaw asserts this theory through the memoirs of Gloria Swanson, one of the greatest and sexiest stars of the 1930s, with whom Kennedy had a torrid affair, notorious in Hollywood but studiously ignored by his wife, Rose, who professed not to notice. Nasaw does effectively debunk, by barely referring to it, the Swanson allegation that Boston’s cardinal William O’Connell, a notoriously imperious and abrasive man, attempted to order Swanson to desist from the relationship.

Swanson broke rather angrily with Kennedy and accused him of exploiting her financially. But before that, Kennedy combined his romantic and industrial ambitions in setting himself up as Swanson’s producer and financial adviser. He cast her as the lead in a new film by Hollywood’s most temperamental director, Erich von Stroheim, a “self-destructive madman.” It was shut down midshoot after more than a million dollars had been wasted on it. Kennedy then cast Swanson in the 1929 film The Trespasser, which premiered in Europe very successfully. Afterward, Joe and Rose Kennedy joined Gloria and members of both families on the return ocean passage to New York. Kennedy lavished copious attention on Swanson while Rose, expecting their ninth child (Edward), stayed above it all.

Kennedy flourished in the Depression. He was a pessimist except on the question of his own ability to succeed, and he recognized that America’s prosperity in the late 1920s was uneven and that the stock market was overbought. He sold shares and assets and was largely liquid and nearly debt free when the crash came.

David Nasaw does usefully debunk two Kennedy financial legends: One was that he had made a great financial score on Yellow Cab Company and the original Hertz rent-a-car business. He did moderately well, but John Hertz declined his offer to invest heavily in the car-rental venture. Nasaw also disposes of the malicious canard that Kennedy was a bootlegger during Prohibition. But like many others, Kennedy foresaw the end of the Prohibition folly, which effectively delivered one of the country’s greatest industries into the hands of organized crime. He secured large stocks of premium Scotch and exclusive importing arrangements, founded Somerset Importers and collected huge profits. Kennedy also led a syndicate that included Walter Chrysler, the automobile manufacturer, and the investment banks Kuhn, Loeb Co. and Lehman Brothers. Together they bought large quantities of stock in Libbey-Owens-Ford, an auto-glass manufacturer, and wash-traded huge volumes of stock among themselves while promoting the outright fraud that their company was related to Owens-Illinois, which made glass bottles and presumably would profit from repeal of Prohibition. It was brazen and cynical, but these “pump and dump” activities didn’t include the filing of written misrepresentations. Hence, it wasn’t illegal.

Kennedy’s departure from Pathé Films after it ran into trouble was a case study in the use of insider information. Kennedy arranged the takeout of his own stock in the company, which flattened the interest of uninformed minority shareholders. Then he short sold the stock as the company collapsed into the hands of Kennedy’s buyer, RKO. When he appeared at the subsequent shareholders’ meeting, according to the New York Times, “heavily armed private detectives were unable to preserve order,” although they did prevent physical violence. Kennedy was greeted with epithets but remained relatively unfazed. He short sold other stocks, but he also bought, as long-term investments, shares and other assets that he believed had been sold down to the point of being underpriced in the panic and distress. According to Nasaw, Kennedy’s net worth rose steadily through the Depression, even as deflation flattened values.

LIKE MOST Boston Irish, Kennedy was a Democrat, but he did not support New York’s Irish Catholic governor Alfred E. Smith when he ran for president in 1928 against Republican Herbert Hoover. Kennedy viewed Smith as a clownish Irish pol, rather like four-term Boston mayor James Michael Curley (once elected from a jail cell). This was an unjust rap on Smith. True, he had a broad Lower East Side accent and left school at age ten, but he was a reform governor and scrupulously honest. Kennedy identified with the educated and modern engineer and businessman, Hoover, who had distinguished himself distributing aid in war-ravaged Europe and engineering big projects in China. But Kennedy became concerned during the Depression that the economic and social problems of America were so serious that the United States could blow up in social discord. He had respected Franklin D. Roosevelt from a distance in World War I, noting that he was completely without religious prejudice as he led the pro-Smith faction in the Democratic Party at the 1924 and 1928 conventions. Kennedy saw a necessity for some radical adjustments to avoid complete catastrophe, while Hoover offered nothing but reinforcement of failure.

In this, Kennedy showed far more prescience than most businessmen, who harrumphed and quavered in their clubs, quoting the Bible, Mother Hubbard and Dickens about the immutability of the economic cycle. The Roosevelt-Kennedy relationship was strange. Kennedy had the Midas touch but was completely inept politically; Roosevelt, an unsuccessful financial dabbler, was the all-time heavyweight champion of electoral politics in the democratic world. Writes Nasaw: “What is remarkable about their relationship is how adept Roosevelt was at getting from Kennedy what he needed and how regularly he would resist giving much back.” This was part of Roosevelt’s genius and ultimately extended even to Churchill and Stalin. Kennedy never understood it.

Pullquote: The Kennedys were really only a dynasty for the decade of the 1960s, a glamorous and tragic meteor of a family that fleetingly brightened the sky of America and then passed on.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review