Why Syria Is Not Libya

History offers important warnings for those who think Assad will go quietly.

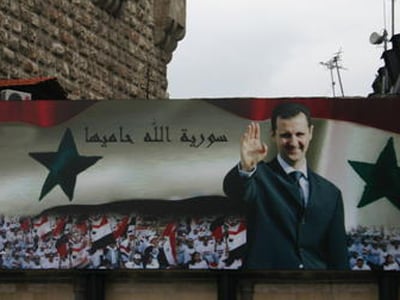

As the violence continues in Syria, the prevailing assumption is that the regime of Bashar al-Assad is on its last legs. Even if it is not dislodged by overt Western action (such as an air campaign similar to the one undertaken in the skies over Libya last year), many believe that a tipping point has been reached that, sooner or later, will result in a change of government—that Assad cannot put down the uprising and that, over time, his regime will be weakened by ongoing defections from his security apparatus.

As the violence continues in Syria, the prevailing assumption is that the regime of Bashar al-Assad is on its last legs. Even if it is not dislodged by overt Western action (such as an air campaign similar to the one undertaken in the skies over Libya last year), many believe that a tipping point has been reached that, sooner or later, will result in a change of government—that Assad cannot put down the uprising and that, over time, his regime will be weakened by ongoing defections from his security apparatus.

This was, after all, how events unfolded in Libya. But Libya may not be the best prism through which to interpret events in Syria.

The first problem is asserting that a minority group cannot maintain its domination over the political system against the demands of an assertive majority. Yet the recent political history of Rwanda, for instance, shows how the minority Tutsi—even after suffering the 1994 genocide—have remained the dominant political class in the country despite constituting only 15 percent of the population, a proportion not dissimilar to the number of Alawites within the Syrian population. Paul Kagame was reelected as president with 93 percent of the vote in 2010, and the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) dominates the parliament. Freedom House ranks Rwanda as a “not-free country,” of course, and the government has a number of tools at its disposal to keep the status quo intact—but the reality is also that a sufficient number of Hutu have supported Kagame and the RPF, identifying with its goals of modernization and development. The current prime minister—Pierre Damien Habumuremyi—is of Hutu ethnicity, just as in Syria a number of key posts were allotted to Sunnis loyal to the regime.

The second problem with a Libya comparison is assuming that a continuation of violence in the country favors the anti-Assad uprising. The case of Algeria is instructive in this regard. The military government canceled the 1992 elections that would have brought the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) to power. The initial impetus for the attempted revolution that followed was to force an unpopular military government to recognize the “will of the people” as expressed in the first free elections held in Algeria since independence. However, over time, many of those who had been FIS voters—particularly the middle class—turned against the antigovernment forces, particularly after the insurgents themselves began to use terror as a tactic in the struggle. The small merchants and shopkeepers were increasingly alienated by the violence unleashed by the militants struggling against the government.

Of course, the world is unlikely to stand by and allow the Syrian government to engage in Algerian-style “eradication” of antigovernment forces. But the fact that the Algerian regime survived a bloody ten-year insurgency that claimed up to 150,000 lives because, in the end, most Algerians preferred an end to violence and some degree of stability, points to a possible evolution of events in Syria. To combat better-armed and better-equipped forces of the regime, the opposition must increasingly rely on a guerrilla struggle; at some point, Syria’s majority Sunnis may decide to opt for some sort of Rwanda-style accommodation with the regime and eschew further confrontation.

Some have wondered why leading figures in the regime don’t force the resignation of Bashar al-Assad. But the dynamics of politics in other nondemocratic regimes such as North Korea and Cuba help to explain why elites may coalesce around a ruling family and promote “republican monarchism”—presidents are who hereditary kings in all but name. The Kims and Castros of the world are viewed as the only ones capable of holding the regime together and are the only figures that everyone can agree upon. We are seeing a version of this problem unfolding right now in Venezuela, where an ill Hugo Chavez is seen as the only person who can hold together his Bolivarian revolution; none of his possible successors are capable of leading his movement.

Finally, we have not seen major defections from the Syrian regime as occurred in Libya. The Baath party in Syria created, in essence, an “alliance of minorities”—especially Alawites and Christians—who remain fearful of what might befall them in a Sunni-dominated state. Indeed, some believe that plan B, should the current regime be unable to retain control over the entire country, is to ensure that an Alawite-Christian enclave could emerge.

If the goal of U.S. policy is regime change in Syria, then assuming Assad’s government has been mortally wounded and its fall is but a matter of time is a risky gamble. Either the West will have to become involved to give the current regime a shove, or it—and the Syrian opposition—will have to do more to entice larger-scale defections from Assad. So far, for instance, there seems to be little willingness to contemplate a decentralized post-Assad Syria that would give substantial autonomy to different regions, creating, in effect, a guaranteed Alawite safe haven.

The United Nations now warns that Syria is descending into “catastrophic civil war.” But there’s no reason that it cannot be a prolonged and bloody conflict. There is no neat solution to Syria’s woes looming on the horizon.

Nikolas K. Gvosdev, a senior editor at The National Interest, is a professor of national-security studies at the U.S. Naval War College. The views expressed are entirely his own.