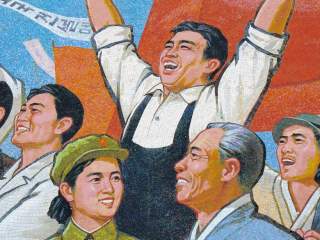

2015: The Year of Korean Reunification?

"A rich and resurgent Korea of 75 million people would be a major regional power..."

The Korean peninsula is in a dangerous state of flux. The border between North and South Korea is one of the most heavily militarized places in the world. The North Korean regime has been characterized as "fractured, unsettled and perilously fragile." And the Supreme Leader of North Korea, thirty-one-year-old dictator Kim Jong-un, has mostly disappeared from public view. The government insists that he is alive and well, releasing photos that purportedly show Kim inspecting government offices and a new housing development while recovering from a pulled tendon according to one report. True or not, Kim's reappearance hardly answers all the questions sparked by his absence.

The last battlefront of the twentieth-century world wars lies dormant across the 38th parallel in Korea. On August 17, 1945 General Order Number 1 of the U.S. occupation forces in Japan directed that Japanese troops in Korea north of 38 degrees N longitude should surrender to the forces of the Soviet Union, while Japanese troops south of that line should surrender to the forces of the United States. Six decades and one major war (1950-1953) later, today's demilitarized zone separating North Korea from South Korea follows roughly the same line.

While South Korea has transformed itself from a repressive military dictatorship into a free country with a vibrant democracy, North Korea remains a repressive military dictatorship—but with a twist. Absolute power in North Korea has been passed down from father to son to grandson over three generations of the founding Kim family. Kim Il-sung was installed as the North Korean dictator by the occupying Red Army. His son Kim Jong-il ran the country further into the ground in pursuit of advanced rockets and nuclear weapons.

Kim the Third, Kim Jong-un, took power after the death of his father in 2011. Though experts agree that his grip on power has been firm, his health seems relatively poor for a man in his early thirties, and his reign has been erratic at best. For weeks, rumors have circulated that Kim may have been deposed in a palace coup. He was last clearly seen in public on September 2, 2014. South Korean intelligence and Western experts insist they are confident that he is still in charge, but questions are inevitable.

After all, it is an odd move for a charismatic dictator whose rule is legitimated by an all-pervasive personality cult to stay out of the public eye for more than a month. In the absence of evidence, logic suggests that if he could appear in the flesh, on television, or even on the radio, he would. It is hard to imagine that he could be too sick to make a radio broadcast reasserting and reinforcing his hold on power, especially if he is up and about making spot inspections.

It seems more likely that Kim has been isolated or at least that his rule has been threatened. On October 4, the Washington Post reported that "the men thought to be second and third in command" made an "unusual and unannounced trip" to the South. As if that were not enough to bring a reclusive dictator out of hiding, over the ensuing week, North and South Korean forces exchanged fire both on land and at sea. There has still been no word from the Supreme Leader about these developments.

If Kim were to be deposed by his inner circle, what would be the implications for Korea? The Kim family may have an interest in remaining the hereditary dictators of an impoverished domain of 25 million people, but North Korea's top bureaucrats have little incentive to stay the course. Comparative analyses suggest that they would do much better to become developers, real-estate tycoons and "fixers" intermediating South Korean investment in the North. Like the former apparatchiks and generals of many other postcommunist countries, they would benefit enormously from an end to self-imposed isolation.

The consensus among professional policy analysts is that the South Korean government wants to pursue eventual, but very gradual, reunification with the North. You can't always get what you want. The South Korean population broadly supports reunification, and if a newly emerging North Korean leadership asks for reunification, it will be difficult for the South Korean leadership to say no. If the wave of popular euphoria that swept over Germany in 1989 is any indication, the South Korean leadership will not have the opportunity to say no.

Is Korea poised for reunification? Every link in the logical chain that leads to that conclusion is potentially highly contentious, but the chain is there and the logic is clear. The longer Kim Jong-un remains in the background, the more likely this scenario becomes. The South Korean government may not want to contemplate the costs of absorbing 25 million brainwashed new citizens into the South's population of 50 million, but South Korea is a democracy. As long as South Koreans have strong emotional ties to relatives, ancestors and long-lost villages north of the 38th parallel, their government will have no choice but to go along.

China, Japan and Russia may not approve of Korean reunification, but they won't be able to prevent it any more than France, Great Britain and Russia could forestall German reunification. That won't stop them from trying. A rich and resurgent Korea of 75 million people would be a major regional power, even if (as is likely) it were to renounce North Korea's nuclear ambitions. But people power will carry the day. Let's face it: no foreign government wants to adopt North Korea's population, not even China. The South Korean government may have no choice. Korean unification may be only a matter of time, and not much time. Don't be surprised if it comes in 2015.

Salvatore Babones is an associate professor of sociology and social policy at the University of Sydney. He is a comparative sociologist who writes on comparative international development and on quantitative methods for the social sciences.

Image: Flickr/yeowatzup/CC by 2.0