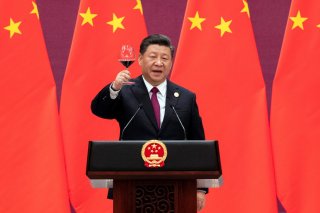

After Sixth Plenum, China Belongs to Xi Jinping

The Chinese Communist Party’s recently concluded and highly debated Sixth Plenum, a gathering of all 376 full-time and substitute CCP Central Committee members, only further cemented Xi’s political control and his “authoritarian image” within the party and military echelon.

Xi Jinping’s gradual consolidation of political power has put the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the global spotlight for some time now. A central feature of this power consolidation is the transformation of the Chinese government’s decision-making process from a collective endeavor to a singular one, dictated primarily by Xi himself. The CCP’s recently concluded and highly debated Sixth Plenum, a gathering of all 376 full-time and substitute CCP Central Committee members, only further cemented Xi’s political control and his “authoritarian image” within the party and military echelon.

As the world intently scrutinized the CCP’s latest plenum outcome, the Sixth Plenum passed an important milestone resolution on “major achievements and historic experiences” since the CCP’s founding one hundred years ago in 1921. As widely reported, only the third of its kind, the CCP resolution enshrines Xi as a part of the Chinese constitution, placing him in a position equivalent to Mao Zedong who is credited as the founder of the country, and Deng Xiaoping, a reformist leader who brought about a period of immense growth and prosperity that transformed China into the world’s second-largest economy. In fact, the past two resolutions of this nature came under Mao in 1945 and Deng in 1981, and signified their stalwart status and power as top leaders of the country.

For Xi, the resolution has further strengthened the foundation for his bid for a third term in office, while putting him as a tall leader in CCP’s historical “leadership image” canvass. What do the sixth plenum and the passage of this resolution indicate about the future of Xi’s political authority and leadership, and more importantly, China’s role in the regional security architecture?

Xi Between Legacy and Leaderships

The CCP’s Sixth Plenum was crucial as it paved the way for decisions on China’s leadership future at the next year’s National Party Congress. Over the past three decades, the CCP has generally utilized the plenum meetings to address party issues, particularly on key appointments, philosophy, and party-building matters. In fact, Chinese leaders often get their power from the post of the general secretary of the CCP—showing the importance of a leader’s political standing within the party in sustaining his power in the country’s administration.

While Xi’s predecessors have all relinquished power or had resigned observing the compulsory guideline of two five-year terms, Xi himself is gearing up for a third term or what has been recognized as his bid to become “president for life.” The question now remains whether the party will maintain this point of reference of a two-term limit for the president and his top administration (set by Deng Xiaoping), particularly the casual retirement age of sixty-eight. Alongside Xi, Premier Li Keqiang also will be finishing his two-service term limit in mid-2023. At the same time, almost twelve of the twenty-five individuals from the Politburo will be more than sixty-eight in October 2022.

It is pertinent to remember that Xi’s rapid ascendance to and consolidation of power in 2012-2013 was marked by a widespread Mao-like anti-corruption campaign that led to the arrest and punishment of many CCP officials. However, over time, the campaign has come to be used as a “cover” to target and eliminate Xi’s political opponents, including Bo Xilai and Zhou Yongkang. Xi’s anti-corruption crusade against rivals has contradicted and cast a shadow over the image of a unified, dependent, and loyal government that China broadcasts. An alleged coup attempt in 2017 also saw punishments meted out to those involved under the guise of corruption charges; Once removed from power, they were replaced with Xi’s long-time friends.

Now, a similar trend is resurfacing with vigor in China in light of the upcoming Congress in 2022. For instance, China’s top disciplinary body, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), moved against two former high-ranking security officials, Fu Zhenghua and Sun Lijun, on charges of corruption. Their prosecution was shrewdly timed as part of Xi’s wider strategy for power consolidation; the act was a final strike against Xi’s remaining opponents ahead of the Twentieth National Party Congress. It sought to end any power struggles and promote and secure positions for Xi’s allies.

Fu and Sun’s removals opened the door for the rise of Xi’s close friend and confidant, Wang Xiaohong, the current vice minister of public security. Several similar personnel changes have taken place within the CCP Central Committee, with close confidants of Xi taking over key roles in vital provinces like Hunan, Tibet, and Jiangxi. Notably, Vice-Premier Sun Chunlan was absent at the CCP’s secret Beidaihe conclave; While this may be because the seventy-one-year-old politician will be retiring, it also indicates the slim chances of her staying on in any leadership capacity—especially as she remains a close confidant of Premier Li Keqiang as reports of internal conflict between Li and Xi have gained traction.

In this context, the Sixth Plenum acted as a precipitator to Xi’s personal, ideological, and organizational goals, reiterating Xi’s strong personal position in the run-up to the decisive Twentieth National Party Congress in 2022, and demonstrating his “core position” and significance for the achievement of the Chinese dream of great rejuvenation. The Sixth Plenum was also the penultimate plenary assembly of the Nineteenth Central Committee, which is set to be dismantled with the election of a new Central Committee at the Twentieth National Congress in the second half of 2022. Amid such internal power shifts, the adopting of the “Resolution on Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the CPC’s 100 Years of Endeavors” marked a clear, ambitious, and momentous personal triumph for Xi.

Xi’s China vis-à-vis Adversary Powers

Beyond its implications for domestic political power dynamics, the Sixth Plenum session also has inferences for China’s ambitions on the regional and global stage. The communique released after the plenary session clearly identified Xi as the “principle founder” of the “Xi Jinping Thought” that will continue to guide China’s rise, much like the Marxist philosophy that defined Chinese thought in the early 1900s. In other words, Xi was formally recognized as the driving force behind China’s pursuit of the second centennial goal—to become a “great modern socialist country” by 2049—for a bright future. Accordingly, the Sixth Plenum was a step towards Beijing realizing its goal to attain great power status in both the regional and international domains. In this vein, to further advance towards the Chinese dream of national rejuvenation, the plenum document highlighted the country’s growing military capabilities, economic strength, and role as a global player.

Furthermore, the Sixth Plenum—which came at a critical time coinciding with Xi’s first virtual meeting with U.S. president Joe Biden amid steadily heightening of U.S.-China tensions—also emphasized the need for “major-country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics on all fronts.” Importantly, it emphasized the “One Country, Two Systems” policy as a way of achieving “national reunification” with respect to Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Tibet. The CCP’s language on Taiwan particularly stands out; the communique stated that the CCP “firmly opposes” any “separatist” attempts to promote Taiwanese independence. Though this strong wording is not coming for the first time, the CCP’s continued focus on Taiwan is meant to impress upon the West that it should prepare to meet a stronger China under Xi in the future. In other words, this reiteration of a strong stance on Taiwan indicates that tensions will continue to rise in the Taiwan strait with unceasing, and perhaps increasing, air and maritime incursions into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone (ADIZ) and maritime boundaries. With Taiwan becoming a key flashpoint of contention for both the United States and Japan, increased friction here will likely cause further tensions in China’s ties with these powers.

For New Delhi too, Xi’s consolidation of power has significant implications. It implies a continuation, and even possibly a bolstering, of Beijing’s aggressive tactics at New Delhi’s northern borders; India can expect ongoing militarization along the India-China disputed border, likely under an astute Tibetan plateau military command that draws its power under Xi’s authoritarian military structures. In this context, Tibet’s place in India-China relations, the China-Pakistan nexus, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), and water politics with respect to the Brahmaputra River are likely to be a source of continued tensions and areas where Beijing will be reluctant to compromise. Further, India might witness a gradual increase in China’s footprint in the Indian Ocean, India’s backyard, through China’s developmental adventurism under the banner of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Similarly, Tokyo should be prepared for China’s continued maritime adventurism in the East China Sea. In the South China Sea (SCS) as well, Chinese incursions and aggression are likely to persist. Even as China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations agree to a “comprehensive strategic partnership” which includes a substantive negotiation on the SCS’s Code of Conduct, the CCP’s resolute language at the plenum contradicts such a stance. With Australia’s growing security alignment with the United States, such as via the establishment of the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) trilateral, China-Australia tensions show little sign of thawing. Hence, as Xi cements his place in Chinese political history, the future of CCP’s global ambitions and regional power politics can only be expected to become terser with time.