Ali Shamkhani: Rouhani’s Bridge-Builder to the Arab World?

Can he make his mark on Iran's regional policies?

Iranian-Saudi relations are once again slipping. A new round of war of words is in the works, each side blaming the other for scorched-earth policies that are fueling the fires of conflict across the Middle East. It was meant to be different by now. It has been over a year since Hassan Rouhani’s election and his pledge to reset ties with Riyadh. The on-again/off-again process of détente, however, was never meant to be a breeze, given the troubled history of Iranian-Saudi relations. It was in this grueling context that Rouhani’s appointment of Ali Shamkhani—the most prominent ethnic Arab in Iran’s state apparatus since 1979—caused so much hope. Shamkhani was thought of as Rouhani’s bridge-builder to the Arab World, but he has yet to prove transformational on that question. In fact, Shamkhani’s fame is rooted in his deftness to hit back against hardliners on the home front. He is an old Revolutionary Guardsman who over the years moved to Iran’s political center. But he is no regime dissenter, and don’t expect him to defy the policy consensus in Tehran.

A Blunt Man

It was in September 2013 that President Rouhani appointed the fifty-nine-year-old Shamkhani as the head of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), a key organ in Tehran that makes strategic defense and security policies under the guidance of the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Reformists and moderates in Tehran were delighted by Shamkhani’s appointment.

He is a practical, moderate voice that succeeded Saeed Jalili, an austere hardline ideologue who was, by the end of his term at the SNSC, ridiculed as a novice with a faint notion of the ways of international diplomacy. Even Ayatollah Khamenei’s chief foreign-policy advisor, Ali Akbar Velayati, publicly scolded Jalili for his diplomatic ineptitude that was deemed to only have exacerbated Tehran’s international troubles.

Shamkhani’s appointment by Rouhani was meant to help undo the damage done by Jalili and the man who appointed him, former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Shamkhani’s moderate track record, however, in no ways makes him a regime outsider. He is very much a product of the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and the coming of the Islamic Republic. To say this, his regime credentials run deep. While he was nominated by Rouhani, Shamkhani’s arrival at the helm at the SNSC would not have been possible without the approval of Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. Khamenei, who has known Shamkhani since their working days together during the Iran-Iraq war, opted to appoint him as one of his two personal representatives to the SNSC on top of Shamkhani’s role as the head of the council.

Stellar Regime Biography

Shamkhani, a father of four, hails from Iran’s southwestern province of Khuzestan, adjacent to Iraq. Over the course of the last century, the province has evolved to become one of the most strategically important regions of Iran. It is home to most of Iran’s oil fields, the lifeline of the country’s economy. It is also home to most of Iran’s ethnic Arab minority. In September of 1980, when Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded Iran, Baghdad called on the Iranian Arabs to join the Iraqi army against the “Persians.” The call fell on deaf ears. Iran’s ethnic Arabs fought alongside other Iranians to repel the Iraqis. And among them a young Shamkhani stood out.

He began as an anti-Shah activist in his youth, although his political track record prior to the 1979 revolution is sparse. But his timing proved opportune and after the revolution, he quickly became one of the founders and the first commander of the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC) branch in his native Khuzestan province.

Shamkhani became part of a group of young, influential Islamist war volunteers that orbited the clerical leadership in Tehran. As a top commander in the IRGC, he worked closely with Prime Minister Mir Hossein Mousavi, a man Shamkhani would defend even after Mousavi was ostracized by the regime following the 2009 presidential elections.

Back in 1988, when the Iran-Iraq War ended and the Ministry of the IRGC was disbanded, Shamkhani found himself out of a job. His personal relations once again proved invaluable in keeping him within the top echelons of the regime. Ayatollah Khamenei, who became supreme leader following the death of Ayatollah Khomeini in June 1989, promoted Shamkhani to the rank of admiral, but transferred him from the IRGC to the Artesh, Iran’s regular armed forces. Shortly after, Shamkhani was given the joint command of Iran’s Artesh and IRGC navies. In the next eight years, he led the combined effort to modernize both the doctrine and the hardware of the Artesh and IRGC naval forces.

In 1997, reformist president Mohammad Khatami appointed him as defense minister, a strong sign that Shamkhani was capable of broad appeal across Iran’s factional politics. The appointment, however, did not stop him from running as an independent for the presidency in 2001 where he came third with 2.6 percent of the vote (Khatami was reelected by 77 percent of the vote). Nonetheless, Khatami kept Shamkhani as defense minister in his second term (2001-2005). In subsequent years, Shamkhani has dismissed his 2001 presidential bid as a case of “rivalry in friendship.” He defended his candidacy by arguing that he had “things to say,” but above all wanted to show that military men can and should enter higher political office through the ballot box.

Disapproval of His Old Comrades

Shamkhani’s line about military men entering politics through the ballot box was nothing short of a jab at some of his old comrades that still wear the IRGC uniform. It was not an argument he put forward in 2001 when he ran for office, but floated this reasoning about a decade later following the hotly disputed 2009 presidential elections.

That was an election where many thought the IRGC top commanders helped engineer a fraudulent victory for Ahmadinejad. Shamkhani, the old IRGC commander, found himself in agreement with those that see present-day IRGC leaders on a binge for political power, but pursuing it largely through underhanded if not outright illegal means.

That view of the IRGC as a political predator is one that Rouhani shares with Shamkhani. It was perhaps no coincidence that one week after Rouhani nominated Shamkhani, the Iranian president openly warned the IRGC to stay out of politics.

A Man with a Mandate

At first when he was appointed, there was uncertainty about what Shamkhani at the SNSC could achieve. That Rouhani early on transferred responsibility of the nuclear file from the SNSC to the foreign ministry under the leadership of Javad Zarif made Shamkhani’s capacity to be a transformational figure less likely. But it quickly became apparent that Rouhani’s intention had all along been to make Shamkhani into Tehran’s point man in its troubled ties with the Arab world. And among the Arab countries, Saudi Arabia holds a special place in Tehran.

Meanwhile, Shamkhani seems to cherish that role. “I am an Arab. When I went to Saudi Arabia and they discovered I am an Arab they were surprised. [My ethnic Arab background] became a way to move closer to the Saudis.” In 2000, as defense minister with his focus on regional security involving the littoral states of the Persian Gulf, Shamkhani visited Riyadh where a security agreement was signed. The Saudis subsequently gave him the prestigious Order of Merit of Abdulaziz Al Saud. Unsurprisingly, Shamkhani’s appointment to head of the SNSC was widely welcomed in the Arab World.

There has been much speculation that Shamkhani is already making his mark on Iran’s regional policy. Many saw Tehran’s decision to abandon Nouri Al Maliki as a sign of moderates such as Shamkhani gaining the upper hand in the debate at the expense of Iran’s hawks—such as the present-day top commander of the IRGC—associated with Tehran’s status-quo policies.

But Iran’s change of heart about Maliki’s future had far more to do with unfolding events on the ground in Iraq than any policy shift in Tehran. For now, Iran’s regional policy is largely following the same pattern of recent years. In one striking example, the case of the Syrian civil war, the arrival of Shamkhani at the SNSC has made no tangible difference with Tehran still committed to the survival of the Assad regime.

Among his supporters, Shamkhani is still mostly respected for his candor and readiness to speak against his old IRGC comrades on the home front. It remains to be seen if this trait can in any way also contribute to a transformation of Tehran’s Arab policy under Shamkhani’s leadership at Iran’s Supreme National Security Council.

Alex Vatanka is a Senior Fellow at the Middle East Institute in Washington, DC.

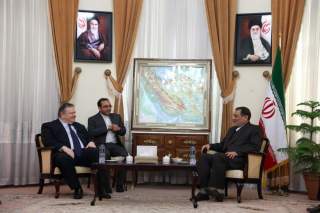

Image: Flickr/Υπουργείο Εξωτερικών/CC by-sa 2.0