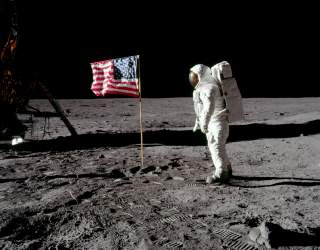

The Apollo Project Question No One Dares Ask: Was It Worth It?

Lunar exploration led to no major scientific discoveries. As Nobel Laureate Steven Weinberg put it in 2007, “[T]he whole manned spaceflight program, which is so enormously expensive, has produced nothing of scientific value.” One analyst went so far as to suggest that the most significant finding gained from the Apollo missions was the discovery that the Moon’s crust is thicker on one side than on the other.

The current celebrations of Project Apollo’s achievements highlight how slowly nations learn from experience. The United States is again committing itself to go to the Moon, and from there to Mars, sending humans rather than robots. We are again promised that such an undertaking will lift the human spirit and provide us with major scientific discoveries, and even a haven to retreat to, in case life on Earth becomes unbearable. In 1964, I wrote a book in which I pointed out that the funds, and especially the research and development resources, dedicated to a lunar visit would be better spent on Earth; that if we had to reach into deep space, it would be much less risky and less costly to send robots than humans; that most benefits in space are to be found in near—and not deep—space; and that the various claims made about Project Apollo would be found to be hollow. (I called the 1964 book The Moon-Doggle.)

If we assess Project Apollo realistically, and learn from it for future space missions, then what do we see?

Lunar exploration led to no major scientific discoveries. As Nobel Laureate Steven Weinberg put it in 2007, “[T]he whole manned spaceflight program, which is so enormously expensive, has produced nothing of scientific value.” One analyst went so far as to suggest that the most significant finding gained from the Apollo missions was the discovery that the Moon’s crust is thicker on one side than on the other.

We found no gold, silver, or any other materials worth carrying back to Earth.

The Moon did not serve as a high ground for a military base.

Project Apollo did not increase the prestige of the United States overseas, and it provided inspiration at home only to a limited segment of the population for a short period of time. Pathways to Exploration: Rationales and Approaches for a U.S. Program of Human Space Exploration, by the National Research Council of the National Academies, has forty years of data that indicate that, “[A]t any given time, a relatively small proportion of the U.S. public pays close attention to space exploration.”

NASA is now pushing to make it a top priority to send humans, not robots, on a mission to Mars, i.e. to deep space. NASA’s current plans call for putting humans into the red planet’s orbit by the early 2030s, as the first major step of achieving the dream of those who wish to see humans living on multiple worlds.

However, there is little the astronauts did on the moon that robots could not have done. And, since then, robots have become much more sophisticated and agile than they were in 1964. Moreover, the most notable findings in astronomy, astrophysics, and cosmology have been made using satellites, probes, rovers, and sophisticated telescopes—not astronauts. Robotic spacecraft have surveyed every planet in our solar system. One of the more important astronomical discoveries of our time, the detection of the cosmic microwave background radiation, was achieved with an Earth-orbiting satellite. Hubble, the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, the Kepler Space Observatory, and scores of other telescopes have served as the major instruments of scientific discoveries. Sir Martin Rees, Britain’s Astronomer Royal, stated in 2010 that “the practical case [for human spaceflight] gets weaker and weaker with every advance in robotics and miniaturization.”

Furthermore, traveling to Mars is much more difficult than visiting the Moon, and it is extremely dangerous. The technology to transport people to Mars safely does not yet exist. The first manned trips to the planet are likely to entail months of high-risk travel. That’s partly because the 140-million-mile journey would expose astronauts to prolonged, intense radiation, and scientists have not yet found a reliable way to shield travelers from this danger. Some urged NASA to use volunteers who will understand that they are lining up for a suicide mission.

NASA argues that it takes thirty to forty minutes for an order from Earth to reach robots on Mars, but if astronauts could circulate Mars, then they could give orders within seconds, without having to face the hostile Martian environment. But what is the rush? And is it worth spending many billions and risking lives to provide quicker communications?

In his book, One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission That Flew Us to the Moon, Charles Fishman argues that I was wrong to hold that the United States should focus its resources on Earth rather than on lunar exploration because Project Apollo funded jobs for hundreds of thousands of people and resulted in technological investments that laid the groundwork and created a societal appetite for the digital products that now populate our lives. First of all, several of these so-called spillover effects (they were not originally part of the mission) resulted in work done by DARPA, the research arm of the Defense Department, not NASA. Second, I fully acknowledged that there were some such benefits, writing that even if you merely burn fifty billion dollars, you get some heat and some light. However, one should also expect such spillover effects from missions here on Earth.

The main lesson of Project Apollo is that we should focus on urgent missions on Earth. If we must invest in space exploration, then facing new Chinese challenges in near space should get priority. And we should send robots to Mars and patiently wait for their reports, even if takes a whole hour.

Amitai Etzioni is a university professor and Professor of International Affairs at The George Washington University. His next book, Reclaiming Patriotism, will be published by University of Virginia Press this summer.

Image: Reuters