China Dreams of America Alone

Washington's poor treatment of its allies isn't helping either.

As the prospect of a U.S.-China economic confrontation grows more likely by the day, Beijing takes comfort in the ongoing tensions between the United States and its allies that flared anew during President Donald Trump’s recent trip to Europe. American efforts to push back against China’s mercantilist practices will falter without the support of key allies—above all Europe —where frustration with the Trump administration today outweighs serious concerns about Beijing’s economic behavior. If current frictions endure, Beijing is likely to believe—not wrongly—that it can isolate the United States from its allies, rebalance trading relationships, and ride out temporary economic disruption.

Chinese thinkers have long recognized that U.S. alliances are America’s most important comparative advantage in the geopolitical competition for twenty-first-century preeminence. With allies, the United States achieves more. Without them, its position as the world’s leading power is increasingly precarious.

Even if President Trump is not attuned to this, China’s President Xi Jinping certainly is. Indeed, over time, Xi’s speeches have implicitly criticized America’s “outdated geopolitical maneuvering” and “cold war mentality.” In a 2014 speech outlining his regional vision, Xi articulated a future in which, “Asian people, through strengthening cooperation, have the abilities and knowledge to achieve peace and stability in Asia.” Notably absent from Xi’s vision is American leadership in the Indo-Pacific region.

In fact, China has taken concrete steps to undermine the strength and resiliency of U.S. allies.

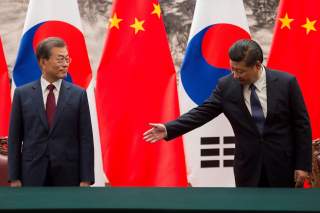

In South Korea, China perpetrated a long-term campaign to exact economic revenge on Seoul in response to its decision to deploy the Terminal High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) system, which China maintains jeopardizes its deterrence capabilities. Beijing did not believe American and South Korean assurances that THAAD focuses solely on the ballistic missile threat from North Korea. South Korean conglomerate Lotte, which sold the land housing THAAD to the South Korean government, was forced to cease operations in China due to “fire code violations.” In the tourism sector alone, South Korea lost an estimated $5.1 billion in missed revenue from Chinese tourists who Beijing prevented from traveling to South Korea. Overall, South Korean exports to China declined by $13 billion from 2015 to 2016. Facing domestic and economic pressures, South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha made a public statement in October 2017 that Seoul would not consider any additional THAAD deployments, effectively ending the row.

Meanwhile, Australia is currently contending with the domestic fall-out from shocking revelations about the depth of the Chinese Communist Party’s political influence within its own democratic system. In December 2017, Australian Senator Sam Dastyari was pressured to step-down after questions emerged about the connections between his foreign donors and his controversial positions on Beijing’s territorial claims in the South China Sea. As the public debates within Australia continue unabated, Chinese officials appear determined to halt the public reckoning of their own influence within Australia. New reports have emerged that during the controversial detention of Sydney professor Dr. Feng Chongyi, Chinese state security officials repeatedly asked questions about Dr. Feng’s contacts with John Garnaut, Prime Minister Turnbull’s leading advisor on Chinese influence.

In the Philippines, China is aggressively courting President Duterte. Beijing has employed tactics ranging from investment pledges to arms deals, to dialing back pressure on Manila's maritime claims. The Philippines—once eager to oppose China's expansionist policy in Southeast Asia through diplomatic support to the United States and by granting American troops access to facilities across its strategically located archipelago—is shifting toward China. Facing public questions about China’s recent deployment of missiles to the Spratly Islands, President Duterte stated, “If America agrees to help, which I doubt, they have missiles. But the foot soldiers, America is allergic to that. They have lost so many wars. So China said, ‘We will protect you. We will not allow the Philippines to be destroyed…we are here anytime when you need us.’”

Furthermore, China’s attempts to diminish the U.S. alliance system are not restricted to Asia. President Xi used Chancellor Merkel’s recent trip to China as an opportunity to attempt to drive a wedge between the United States and Germany. In the days leading up to Merkel’s trip, websites affiliated with the Chinese Communist Party highlighted her lack of success in a recent meeting with President Trump at the White House. Moreover, on the margins of the visit, Xi noted China and Germany’s shared commitment to strengthen the multilateral system in the face of resurgent isolationist thinking, even though China’s track record—from its mercantilist trade practices to its militarization of artificial island outposts in the South China—renders Beijing that system’s greatest challenge. Furthermore, following a recent trip to Spain, Portugal, and France, China’s State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi noted that exploring cooperation on the Belt and Road Initiative was necessary, “in the face of the current international situation brimming with uncertainties”—a thinly veiled poke at the United States.

Imitation is the greatest form of flattery. While working to undercut U.S. alliances, China is simultaneously trying to develop new strategic partnerships. However, unlike U.S. alliances, which—despite an imbalance of power—offer allies a degree of equality, China’s strategic partnerships are hierarchical and provide limited gains to partners. Indeed, recent Chinese engagements with Pakistan, Djibouti, and the Maldives have been characterized by scandal and corruption.

To its credit, the Trump administration’s strategic documents have identified China as the most consequential challenge to America’s long-term prosperity and security. However, a series of public rifts between President Trump and U.S. allies—including U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord; repudiation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action on Iran’s nuclear program; steel and aluminum tariffs imposed on allied countries’ industries; recriminations following the Group of 7 leaders meeting; and a divisive NATO summit—cumulatively chip away at the reservoir of alliance goodwill that America must tap to prevail in the strategic competition with Beijing.

Therefore, the Trump administration must consider how its current approach to many U.S. allies risks undermining America’s capability to compete with China. In the Indo-Pacific, U.S. allies could become less willing to host American troops and to defray the cost of their forward stationing, which would make sustaining a U.S. military presence in China’s periphery more difficult and expensive. Globally, America’s allies might become less inclined to share intelligence and engage in the types of cooperative defense research and development that will contribute to the U.S. military’s future qualitative advantage.

On the economic side, some of America’s staunchest allies, namely the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and Germany, are also the largest sources of inbound investment into the United States, supporting high-quality jobs. Additional trade actions against them could deter future inbound investment at a time when the United States must boost its economic growth to compete with China. America’s future prosperity hinges on its innovation edge—which China is actively challenging through its own ambitious domestic science investment and an aggressive effort to acquire U.S. technology. Both the Trump administration and the U.S. Congress are now moving to restrict Chinese investment in sensitive technology areas, but without a similar effort by America’s allies with advanced economies, Beijing will simply acquire its technology elsewhere.

Diplomatically, America’s friends are a force multiplier for U.S. diplomacy. With less support from allies as well as partners, America would find the United Nations an even more inhospitable forum for advancing its domestic priorities and defending its interests. Outreach stemming from the U.S. campaign to maximize pressure on North Korea prompted Mexico, Spain, and Peru to each expel North Korea’s ambassador in retaliation for its nuclear and missile testing. Will allies and partners be as willing to support U.S. leadership on a pantheon of China-related issues if America ignores their views and drags them into prolonged trade and diplomatic disputes? Perhaps not.

If the Trump administration wants to prevail in the intensifying strategic competition with China, it cannot assume America’s allies will automatically align with Washington against Beijing, regardless of American choices on a range of issues they value. Indeed, U.S. allies have thus far publicly demonstrated little appetite to follow America’s lead in taking on China for its violation of intellectual property, even though many privately share similar concerns.

China dreams of America alone. For the United States, a world of weakened alliances would be a strategic nightmare.

Daniel Kliman is the senior fellow with the Asia-Pacific Security Program at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS).

Abigail Grace is a research associate with the Asia-Pacific Security Program at CNAS.

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) gestures towards South Korean President Moon Jae-In (L) during a signing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China December 14, 2017. REUTERS/Nicolas Asfouri/Pool