China's Premature Power Play Goes Very Wrong

"What the region requires is a new kind of balance—not of power or of resolve, but of uncertainty."

Just as China’s strengthened links with Russia will not become an alliance, its bid to sideline maritime Asian institutions will not get far. This is for the simple reason that a growing China cannot easily escape the Indo-Pacific character of much of its destiny. The energy and resources it needs for its continued development will in large part cross the sea. The more that China extols its ‘confidence-building’ conference with countries to its continental west, the more glaring will be its refusal to operationalize risk-reduction measures with its seagoing neighbor. Sooner or later, Beijing will have to compromise its interests with those of a wide range of Indo-Pacific partners, from the United States to Southeast Asia, India to Australia to Japan, and the diversity of their stakes in the maritime commons. As a trading power, China has legitimate interests across this vast blue canvas, but within its institutions, Chinese influence will necessarily be diluted. This is not some conspiracy to contain China’s rightful role. It is simply a description of the context of China’s rise.

For now, though, China is still struggling to come to terms with the unhelpful geostrategic realities of maritime Asia. This is one reason it is trying hard to rattle the United States, its allies and would-be partners with new shows of leadership and confidence. Here, Beijing may well be right in sensing an opportunity. Syria and Ukraine had deepened doubts abroad and within the United States about America’s staying power as leader and close-in balancer, its willingness to take risks when the threat to its interests is not patently immediate or direct. President Obama’s West Point speech—whatever its honorable themes of counterterrorism, closure and restraint—did not reassure Washington’s Asian allies and friends. Secretary Hagel’s subsequent remarks in Singapore—with its warnings against Chinese coercion—probably made up for that in some way, which helps explain General Wang’s discomfort.

Some press accounts have suggested that the public bluntness of Wang and Hagel marks an ugly new phase, an intensification of competition and forceful rhetoric between China and the United States. This is not so new: a related propaganda war between China and Japan has been underway for months or more. Conferences and speeches alone do not alter the strategic dynamic, but may crystallize what is changing in the real world. The Indo-Pacific (or maritime Asia) is still far from a new Cold War, let alone a devastating naval-cyber-nuclear version of 1914. But the next few months will be unusually important to the future security of this region that is becoming the global center of economic and strategic gravity.

Under question is the region’s capacity to craft an order that is at once stable and free from domination by a single power. If China’s latest behavior and rhetoric can partly be explained by an excess of the wrong sort of confidence—premature, misjudged or a conduit for nationalism—then the United States, its allies and partners will need to be firm, yet also careful and nimble, in how they push back. Somehow, the message needs to reach China’s security decision makers that their continued risk-taking could have consequences they cannot control.

What the region requires is a new kind of balance—not of power or of resolve, but of uncertainty. Of late, too much of the uncertainty has been in the minds of America’s Asian allies and partners. Turning this situation around may be a first step towards China’s acceptance that it will have to live up to its ‘win-win’ rhetoric when dealing with all its neighbors. In other words, what is needed now is greater uncertainty among China’s strategic decision makers about how the United States, Japan and the region’s middle powers will respond to—or anticipate—the next coercive move.

Beijing may pretend to shrug off one legal action, but will have trouble sustaining its indifference if Vietnam or additional South China Sea claimants also seek international arbitration with the overt blessing of the United States, the European Union and other champions of a rules-based international system. Stability in the South China Sea, a global shipping artery, is every trading nation’s business. So Washington would be well advised to follow the kind of practical action plan recently advanced by security policy expert Ely Ratner, involving a coordinated assertion of rules-based management of maritime disputes, globally through the G7, as well as regionally through the East Asia Summit. Simultaneously, the United States and its allies, including Japan, are in their rights to signal that they will expand security capacity-building, training and intelligence-sharing when Southeast Asian states invite them to do so in response to new anxieties about China’s actions.

Shifting the balance of uncertainty in Asia need not have a principally military dimension. Even with constrained resources, the U.S. Navy can sustain a visible presence in the South China Sea and, by invitation, in the territorial seas and exclusive economic zones of partners and allies. New anxieties about regional stability will encourage more countries to join U.S.-led maritime exercises and surveillance cooperation throughout the Indo-Pacific. This need not amount to provocation, if combined with persistent invitations for China to begin serious risk-reduction dialogue so that close encounters like the December 2013 USS Cowpens incident become less likely to occur or escalate. The truth is, China’s maritime assertiveness in recent years has not risen relentlessly. Notably, the tempo of sea and air incidents against Japan—though still troubling—has eased this year; the disciplined pushback by Japan’s experienced maritime forces may well be a factor. Beneath the bluster, at least some of China’s security actors must know they cannot be the masters of infinite risk. This will be a long drama and the script is not theirs alone to write.

Rory Medcalf is director of the international security program at the Lowy Institute and a non-resident senior fellow in foreign policy with the Brookings Institution. You can follow him on Twitter: @Rory_Medcalf.

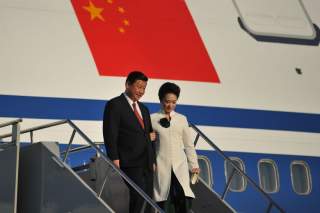

Image: Wikimedia Commons/APEC 2013/CC by 2.0