Don't Exile Thucydides from the War Colleges

War games aren't a perfect tool for teaching strategy.

Nor should we in looking back to the historical record conclude that gaming is a panacea for solving complex strategic problems. Many examples can be adduced to show the limits of gaming. All too often, the results of games are corrupted when they are used to support entrenched doctrine, bureaucratic inertia and sacred budgetary priorities. It’s all too common to replay a game that produces unsatisfactory results: rejigger the assumptions underlying the game until it yields more congenial results.

Rather than liberating the thinking of those who play, then, war games can be abused by participants and onlookers who do not want to challenge conventional thinking, but instead want to propagate a party line. Such games confirm what the leadership wishes to confirm—and leave the service ill-prepared for thinking, determined foes bent on thwarting America’s will.

Games can miss future challenges, furthermore, if the game designers are lacking in vision and tied to conventional scenarios. Before the First World War, gamers at Newport played over and over again scenarios for a conflict with Black (Germany). The games provided the basis for the famous Black War Plan. What did the games conclude? They envisioned a German projection of a battle fleet across the Atlantic that would seize forward bases in the Western Hemisphere, bring the American fleet to battle and impose a blockade on the eastern seaboard of the United States.

These games captured a reality that never came to pass, and wasn’t very likely to. The war that the United States actually did fight was far different from what the gamers played. There was no decisive big-ship showdown pitting the American battle line against a German high-seas fleet; the U.S. Navy fought as part of a coalition with other countries; defense of transatlantic sea lanes against submarines proved to be the navy’s most demanding mission; and the United States ended up deploying two million boots on the ground to the battlefields of France to attack Germany’s army. And for all the virtues of the touted Orange games of the interwar era, they did not envision the employment of nuclear weapons against Japan.

It’s also highly misleading to hype the role of war gaming in naval officers’ interwar educational experience at the Naval War College. If all officers had done in Newport was replay scenarios for fighting against Orange, then the college would have signally failed in its responsibility to equip the minds of naval leaders with the intellectual tools and frameworks for analysis that should be a prerequisite for higher command. At the college, students heard lectures, read extensively, discussed tactics and strategy, and wrote essays—much as they do today.

Indeed, a perusal of Adm. Ernest J. King’s thirty-page thesis on strategy shows that he invested considerable time in reading while attending the college. To write his strategy thesis, King, a future chief of naval operations, read the equivalent of a book a week. He recounts reading classics of strategy like Clausewitz, Mahan and Corbett, as well as works then in vogue on American foreign policy, civil-military relations, high command in wartime and the history of the Great War.

King wrestled with these works and the problems of strategy that they raised. Today’s students need to do so as well and not be told that there is some shortcut to strategic literacy and competence. Games are no substitute for reading and thinking. Games are invaluable when well-educated officers, officials and scholars play them.

If students are not reading the equivalent of a book a week at a war college, then they are not receiving an education adequate to help them take part in the realm of strategic decision-making. Civilians, national-security professionals and military fellows attending graduate-level educational institutions on strategic studies and international relations like Georgetown, Columbia, the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies or the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy are capable of carrying a heavy workload of lectures, reading, seminars and essays. Why, then, are war-college graduates unable to do likewise?

As professional educators, we would be letting down our students if we do not prepare them with disciplined habits of thought that are the products of a rigorous education. We believe in investing in the intellectual development of those in the profession of arms, to include a heavy dose of reading, writing in-depth analyses on complex problems, and grading that informs the students about how to improve their skills in thinking and communicating.

To be a professional entails lifelong learning, requiring a commitment of time to study in preparation for action. This investment in our people’s capacity to think before they act is nothing less than a national strategic imperative. And it’s an imperative we’ve been pursuing through time-tested methods—for generations.

Jim Holmes is Professor of Strategy at the Naval War College, and John Maurer is the Alfred Thayer Mahan Professor of Sea Power and Grand Strategy and served as the Chair of the Strategy and Policy Department. The views voiced here are theirs alone.

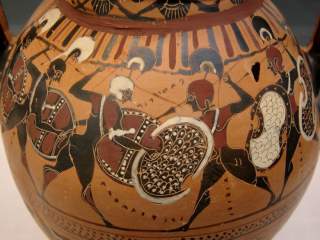

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Public domain