Fighting Back: How Democracies Can Check Authoritarian Aggression

It is past time the United States starts playing offense to shape a balance of power that continues to favor freedom.

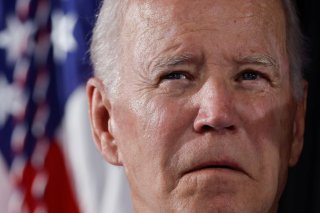

Last week, President Joe Biden and his fellow G7 leaders pledged $600 billion in public and private funds over the next five years to assist developing countries and counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—a key tool of economic and political influence for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It’s a welcome step but could prove a mere drop in the ocean if it is not folded into a broader campaign to fight back against transnational authoritarianism.

The fact is that Xi Jinping and his fellow autocrat Vladimir Putin are on the front foot. From the Solomon Islands to Ukraine, Xi and Putin are using force and varying methods of subversion to co-opt, supplant, or hollow out democratically elected governments to serve their own interests. By equipping repressive leaders with the technology, expertise, and funds to suppress dissent and extend their rule—in exchange for favorable UN votes, access to natural resources, or other concessions—the Kremlin and the CCP are underwriting authoritarian expansion.

The challenge Russia and China pose to democracy is decades old. What is different today is that the threat to democracy is now existential. Xi and Putin have paired their standard suite of influence tactics—for example, economic coercion, election interference, and opaque dealmaking—with more expansive and aggressive moves to shape critical domains, from internet freedom to the basic tenets of sovereignty. This is creating an environment that is fundamentally hostile to vital American interests.

This threat is not lost on the United States. In a recent speech outlining the new U.S. China policy, U.S. secretary of state Antony Blinken said that America “must defend and reform the rules-based international order” in order to realize a future where “universal human rights are respected” and “countries are secure from coercion and aggression.” President Biden has stated the case more pointedly, saying that the United States is in a competition between democracy and autocracy.

The administration deserves credit for its pro-democracy statements and initiatives, and for its continued support for foreign assistance programs that strengthen democratic resilience to authoritarian influence. Yet unfortunately, U.S. policy has often not lived up to the administration’s rhetoric. As China hollows out United Nations institutions and gobbles up Pacific Island outposts, and Russia decimates Ukraine, the White House has too often stood by as our adversaries shape the battlefield. And while this week’s pledge from the G7 is a good start, it falls short of what is needed to win this contest of systems: to aggressively underwrite and expand support for democratic institutions and movements, and ensure that emerging components of the international order are grounded in the ideals of freedom.

In short, we need to go on offense.

The Biden team knows that it cannot singlehandedly check authoritarian aggression and has done well to rally American allies—from galvanizing NATO against Russia’s invasion to deepening the quadrilateral partnership uniting America, India, Japan, and Australia, and launching the Australia-United Kingdom-United States Partnership (AUKUS). The United States and core allies have affirmed support for a world that is safe for democracy; it’s time to underwrite those intentions with actions that take the strategic initiative to put autocracies on the back foot.

Working with D-10 or G-7 allies, the United States should go beyond this week’s proposed assistance efforts and spearhead a campaign to empower democratic movements around the world. This should include moral, legal, and financial assistance to the people on the ground working to advance democracy and under the threat of retribution by authoritarian regimes or their local proxies. Xi and Putin have asserted their right to undermine open societies. The free world must promulgate the right of democratic movements to receive assistance, and fulfill its responsibility to help those seeking to protect or advance democracy in their societies.

The free world must also unite within the UN and other multilateral organizations to arrest the ongoing erosion of those institutions by Beijing and Moscow. UN agencies play an important role in setting international standards and norms; yet Chinese representatives lead two of fifteen such bodies (the International Telecommunications Union and the Food and Agriculture Organization) and are principal deputies at UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization; the International Monetary Fund; and the World Bank. To compete, the United States and its allies must mount coordinated campaigns to prevent China from heading other agencies and reclaim those it currently holds, while also exploring alternative groupings that will more effectively serve the needs of a liberal democratic order.

The existential threat to democracy from Russia and China is perhaps most severe in the digital domain. The CCP has invested heavily in exporting surveillance technology and backdoor access to networks via the state-owned tech giant Huawei; and both Beijing and Moscow have invested in offensive cyberwarfare capabilities with which to blackmail or assault free societies.

The United States must take aggressive steps to ensure a free and open internet based on principles of transparency and openness. This could be accomplished by forging alliances and aligning our regulatory structures with like-minded countries to enable the free flow of information online; developing penalties for countries that build firewalls; and creating incentives for countries to remain open. The United States and its partners can also invest in technologies like satellite internet that deny authoritarians the ability to shut off internet access and preserve the basic right of citizens everywhere to circumvent authoritarian censorship.

Big Tech can and should do more on this front, and the United States and other democracies should design incentives to this effect. At minimum, technology companies should provide tools to activists on the front lines pushing for freedom to keep themselves safe from surveillance as well as develop and distribute technologies to access the internet in countries where it is restricted. Powerful tech companies can also do more to keep their platforms operating in repressive societies rather than bowing to government pressure.

Our leading geopolitical adversaries face no credible deterrent to undermining democratic movements and elected governments. Such political warfare can be just as harmful to stability and American interests as military incursions, but is yet another area in which America’s actions have not lived up to its rhetoric. How can we be serious about competing with China and Russia if we all but give them a pass in this critical domain?

America must start imposing costs to deter and prevent Chinese and Russian interference in foreign political systems and constrain the authoritarian regimes they seek to enable. The United States and its allies should demonstrate their willingness to deploy calibrated, credible economic and military actions in response to verified reports of the Kremlin or CCP political warfare. The United States and its partners should make clear, both publicly and privately, that such incursions will have meaningful consequences.

Washington could work with local partners inside Russia and China to expose leadership corruption, delegitimizing rulers who claim a nationalist mandate to conduct authoritarian aggression abroad even as they systematically steal from their own people. Economic sanctions should be introduced earlier and at a more consequential scale to communicate the costs of proceeding with political warfare. Additionally, China’s membership in the World Trade Organization could be reconsidered as punishment for its continued violation of economic norms. On the military side, so-called “gray zone” tactics—including targeted cyber-attacks—could be deployed to raise the costs for authoritarians who otherwise enjoy impunity in assaulting democratic institutions beyond their borders.

Biden has said that “we are now finally awakened to the challenge” posed by transnational authoritarianism. Yet the question of whether we are prepared to do what it takes to push back remains unclear. Defending democracy is critical to building a free, secure, and prosperous world. We must now pursue policies that go beyond exalted rhetoric to strengthen and empower fledgling democratic institutions and deter our adversaries from their campaigns of malign foreign influence. It is past time the United States starts playing offense to shape a balance of power that continues to favor freedom.

Daniel Twining is President of the International Republican Institute (IRI), where Patrick Quirk is Senior Director for Strategy, Research, and the Center for Global Impact. Both authors previously served as members of the Secretary of State’s Policy Planning Staff at the U.S. Department of State.

Image: Reuters.