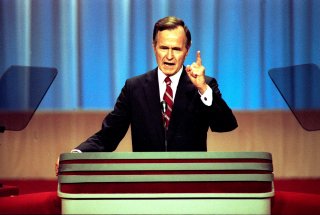

George H. W. Bush's Outsized Legacy

The American people made him a one-term president, but his legacy lives on.

In assessing the presidential legacy of George Herbert Walker Bush, who died Friday at 94, one fact stands out above all others: He was a one-term president by verdict of the electorate. That means the voters in 1992 judged him to have been insufficiently successful in his presidential term to justify retention in office. Unless one wants to argue that the voters were wrong, or perhaps stupid, this electoral judgment must be taken seriously in defining the Bush presidency.

But why did the voters render such a harsh judgment? After all, Bush presided over the end of the Cold War and the breakup of the Soviet Union. He managed that great global development with notable wisdom and appropriate caution, taking care to avoid bruising the sensibilities of the new Russia or undermining its geopolitical interests. Further, he successfully expelled Saddam Hussein’s Iraq from Kuwait through a deftly managed expeditionary campaign, rendered all the more impressive for his refusal to conquer Iraq and get America embroiled in the sectarian and ethnic strife that had beset that country for decades.

And it is widely acknowledged that the first President Bush was a good man and well prepared for the job. No problems approaching crisis level occurred during his watch—no ongoing domestic disturbances or deep recessions or foreign debacles or serious scandals. He scored a significant triumph with his Panama incursion to remove the corrupt and menacing Manuel Noriega from his seat of power there. And his Americans with Disabilities Act, which codified certain civil rights for handicapped persons, constituted a marked achievement in domestic politics.

Thus it isn’t surprising that some historians and commentators have expressed puzzlement over his one-term fate. In a 2011 New York Times column entitled “Bring Back Poppy,” Thomas L. Friedman extolled the elder Bush’s presidency and lamented the passing of his brand of moderate and “prudent” conservatism. He called Bush “one of the most underrated presidents.”

And historian Jon Meacham, author of an excellent Bush biography, wrote after his death that the 41st president had been “done in by the right wing of his own party—a conservative cabal that rebelled against Mr. Bush’s statesmanlike deal with Democrats to raise some taxes in exchange for spending controls to rein in the deficit.”

Here we get to the crux of the Bush legacy. One has to ask whether it is in fact “statesmanlike” to issue a solemn campaign pledge—“read my lips: No New Taxes”—and then renege on it after the presidency has been obtained. Jon Meacham seems to believe that the statesmanship derives from tax increases being the right policy as a means of controlling the fiscal deficit. And yet by Bush’s final year in office, the deficit had increased to 4.58 percent of GDP after Reagan had managed to get that percentage down to a fairly manageable 2.87 percent (from, it must be noted, very high numbers during the deep recession of the early Reagan years). Also, whereas Reagan got economic growth up to an annual average of nearly 4 percent following that early recession, Bush’s average annual growth rate barely cracked 2 percent.

Further, during Bush’s final year, unemployment rose to 7.5 percent from 5.3 percent in 1989.

These numbers suggest that the American people weren’t wrong when they concluded that Bush had squandered the Reagan legacy of high growth (spurred in part by a low-tax regimen), declining deficits and increasing jobs. It’s perhaps natural to suggest that Bush was done in by the conservative columnist Patrick Buchanan, who ran against Bush in the 1992 GOP primaries—and pulled in 38 percent of the vote in New Hampshire and went on to capture nearly three million votes during the primary season. But such an unlikely challenger never could have undercut a sitting president to such an extent unless there was widespread unease among voters about the incumbent’s performance. The same could be said about the independent general-election campaign of industrialist Ross Perot, who garnered 19 percent of the popular vote in 1992 and in the process destroyed Bush’s reelection chances.

Thus one could argue that that “cabal” of right-wingers wasn’t so much bent on imposing on America a harsh new brand of politics as on preserving the successful governance of Reagan in the face of Bush’s inclination to discount and even discredit the Reagan stewardship. That would have been fine with the electorate if his economic policies had been successful. But they weren’t, and therein lay the largest factor in his 1992 fate.

But any president’s legacy consists of multiple elements, and with Bush three in particular deserve exploration. All were in the realm of foreign policy. They are: his administration’s decision to assure Russia that NATO wouldn’t expand eastward; his invasion of Panama to upend a disruptive foreign leader within the American sphere of influence; and his decision to send some 28,000 troops into Somalia, a war-crushed basket-case country in East Africa. The NATO decision was absolutely correct, and it’s a tragedy of history that it was cast aside by subsequent presidents. The Panama incursion, while perhaps debatable, can be justified on geopolitical grounds. But the move into Somalia set America upon a new azimuth of foreign policy that ultimately proved disastrous for the country and other segments of the world.

Lost to many at the time of Bush’s Somalia action was the fact that there was no pretense whatever of any U.S. national interest in such a significant military operation. Of course, expressions of humanitarian impulse had emerged often in American history in support of numerous foreign policy actions. But, without exception, American presidents felt constrained to justify their interventionist actions ultimately on vital national interests. There could be debates, and often were, about whether particular initiatives did in fact conform to American interests, but the very fact of the debates reflected the political reality that humanitarian arguments alone could not justify sending American troops into harm’s path.

Somalia changed all that. Shortly after the troops went in, Time correctly labeled Bush’s initiative a “precedent.” Bush himself, noted the magazine, had called the action “a purely humanitarian action.” Soon Time sought to leverage the Bush action for more foreign policy actions devoid of national interest considerations, particularly in the war-torn Balkans. Shortly after Bill Clinton succeeded Bush as president, the magazine emblazoned across its cover: “Clinton’s first foreign challenge: If SOMALIA, why not BOSNIA?”

Time was not alone. Soon the idea of strictly humanitarian ventures in U.S. foreign policy gained a significant foothold in American political discourse, culminating in Samantha Power’s influential 2002 book, A Problem from Hell. Humanitarian interventionism became a far more powerful national impulse than it had ever been before, in large measure because George H. W. Bush paved the way.

Bush’s Panama incursion inevitably raised questions about America’s role in the world and particularly in its own near abroad. Panamanian strongman Manuel Noriega had turned his country into an axis of drug trafficking and money laundering. His drug deals had generated enough evidence in the United States to get him indicted by two Florida grand juries. In December 1989 Noriega’s goons summarily killed U.S. Marine Lieutenant Robert Paz when he encountered a government roadblock in Panama City. Government officials detained another U.S. officer who had witnessed the shooting, roughed him up, and threatened his life. They pushed his wife against a wall and groped her until she collapsed.

Bush declared the incident a sufficient provocation to get rid of this nettlesome dictator. He unleashed 20,000 troops to attack Panama’s defense forces and other Noriega paramilitary units. Within a day they had destroyed or disarmed the government forces and deposed Noriega.

What was the justification? In his memoir, former Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman (later Secretary of State) Colin Power listed several: “Noriega’s contempt for democracy, his drug trafficking and indictment, the death of the American Marine, the threat to our treaty rights to the canal with this unreliable figure ruling Panama. And, unspoken, there was George Bush’s personal antipathy to Noriega, a third-rate dictator thumbing his nose at the United States.”

We can dismiss Powell’s last justification as frivolous. If America sought to depose every tinhorn dictator who stirs the animosity of a U.S. president, the result would be chaos. Also, Noriega’s contempt for democracy hardly constituted a rationale for spilling American blood. But America does have an interest in curtailing the inflow of drugs. And the Paz killing constituted an even stronger justification. The country can’t allow sanctioned elements within foreign countries to kill Americans with impunity. Then there was the matter of U.S. treaty rights to the Panama Canal, a fundamental element of America’s regional power. That grand waterway was set to be turned over to Panama at a future date, but the handover treaty recognized America’s right to ensure access to the canal. The Paz killing and the lawlessness it reflected raised serious questions about Panama’s willingness to honor that treaty.

While many foreign policy realists questioned such an action, the influential commentator Andrew Bacevich expounded a broader concept when he called the invasion “a classic assertion of a great power’s prerogative to policy its sphere of influence.” In that sense, the invasion comported with similar actions throughout the Caribbean by just about every president from McKinley to Reagan.