How Trump Could Stumble from a Trade War Into a Real War with China

The past five hundred years have seen sixteen cases in which a rising power threatened to topple a ruling power from its position of predominance. Twelve ended in war.

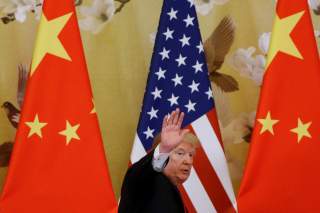

Having just returned from a week in China in which I had the opportunity to talk directly—and listen!—to all of its leaders beneath President Xi Jinping, I came away even more worried about the future of the relationship between the United States and China than I had been. While almost every day brings another tweet or announcement in the war of words, I see the current “phony war” as the proverbial calm before the storm. In one line, my bet is that things will soon get worse before they get worse.

A tariff war between the world’s largest economy and its leading economy would do serious damage to both. But economic damage from a trade war is not the most significant risk posed by current trends.

If Thucydides were watching, he would say that China and the United States are right on script sleepwalking towards what could be the grandest collision in history. Thucydides, of course, was the historian of classical Greece who explained the driver that led Athens and Sparta to the war that destroyed both. Thucydides’s Trap is the term I coined to make vivid his insight about the dangerous dynamic that occurs when a rising power (like Athens or China) threatens to displace a ruling power (like Sparta or the United States). As Henry Kissinger has noted, this concept provides the best lens available for looking through the noise and news of the day to understand the underlying forces at work. The past five hundred years have seen sixteen cases in which a rising power threatened to topple a ruling power from its position of predominance. Twelve ended in war.

On the trade front, President Trump is serious about confronting China. In his view, this is the only way to force the country to make major changes in the way it does business with the United States. For him, the threat of a costly tariff war is essential, since he believes he is playing an economic version of what Cold War strategists called “nuclear chicken.” Under conditions of “mutual assured destruction”—MAD—both nations had nuclear arsenals that could destroy the other after absorbing its best first strike. Thus, if competitive moves up an escalation ladder ended in war, then both would lose catastrophically. But since both nations understood this, each knew that there was nothing for which its opponent could rationally choose to go to nuclear war. If one could maneuver the other into a situation in which it had to choose between yielding on a specific matter and war, then it could have its way. Finding himself approaching just such a fork in the road when the United States discovered the Soviet Union sneaking nuclear-tipped missiles into Cuba in 1962, President Kennedy chose to run what he believed was a one-in-three chance of nuclear war to make his Soviet counterpart, Khrushchev, back down.

President Trump’s threat of a mutually destructive tariff war is part of his response to what he sees as decades in which China has been making Americans choose between risking a trade war, and letting China get away with “rape,” as he put it in the campaign. They have been stealing American firms’ intellectual property, forcing American firms that wanted to enter their market to transfer proprietary technologies to Chinese competitors, subsidizing those competitors, and then dumping excess production. In Trump’s tweets, one can sense an admiration for the Chinese bravado. Indeed, he blames his predecessors even more than he does their Chinese counterparts—since they allowed the Chinese to get away with outrageous behavior rather than standing up for America. Facing off with China would, of course, require taking risks—even risks of a trade war. But In his view, that is the president’s job.

It is noteworthy that in calling out China’s abuses of the global trading system, Trump has struck a responsive chord. After decades of overlooking Chinese violations because they were a “developing country,” the pendulum has now swung. When reliable Trump critics like the leading evangelist of a “flat earth” (Tom Friedman) declares that on trade with China “Trump is right,” and the leading herald of globalization (Fareed Zakaria) declares “China is a trade cheat,” it does not take a weatherman to know that the tide of conventional wisdom has turned.

Trump’s tweets and tariffs have gotten China’s leaders’ attention. After the first meeting of the two presidents at Mar-a-Lago and Xi’s royal welcome of Trump in Beijing, they had hoped that their cocktail of flattery, pomp, and ceremony would suffice. No more. At this point, if the United States will tell them what it will take to resolve the dispute, they are ready to make significant concessions. For example, in the last face-to-face meeting between senior officials, Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin gave China’s economic czar Liu He Trump’s demand that China cut $100 billion off its $375 billion bilateral trade deficit in 2018. The Chinese immediate response was “impossible.” But while I was in China, I offered my view that this was not actually all that hard. Indeed, I gave Vice Premier Lie He—who was a student at the Kennedy School two decades ago—three ways to do this, the easiest of which would be for China to simply buy $100 billion of Alaskan gas and Texan-Louisianan oil for delivery as soon as the infrastructure for delivery is in place.

Chinese leaders worry, however, that the threat of tariff war to coerce changes in established practices is just one front in what may become a wider economic war. They read the Trump administration’s veto of Broadcom’s purchase of the fourth largest semiconductor producer, the American-based Qualcomm as the first shot in increasing restrictions of Chinese purchase and investments in U.S. technology companies and startups. And in seeing this as a harbinger of what’s to come, they are indeed correct.

Beneath their general unease is an even deeper fear about a fundamental shift in the way Washington thinks about China and how the United States should relate to it. For four decades, Republican and Democratic administrations alike saw China as a “partner” or “strategic partner.” But the Trump administration now publicly calls China a “strategic rival” or “adversary.” Obama, Bush, and Clinton pursued a strategy of engaging China and welcoming its integration into the global economic and security order the United States has led for seventy years. The Trump administration has declared that effort a “failure,” and the admission of China into the WTO a “mistake.” Instead, it has shifted to a new strategy it calls “confrontation,” “competition,” and “rivalry.”

Initially, China’s America watchers put this down to just Trump being Trump. But they are coming to the view that while Trump’s language may be more colorful than that of others, this fundamental reassessment of China has now engulfed the entire Washington political class and national-security community. As one Chinese interlocutor put it, all of Washington seems to have done a “backflip.” They pointed to the recent cover story of The Economist that shouted: “How the West got China wrong,” and the Foreign Affairs article by the architect of Obama’s “pivot” to Asia, Kurt Campbell, arguing that all American policymaker’s “fundamental assumptions” about China and American policy towards China “have turned out to be wrong.” Another Chinese official posed what he meant as a rhetorical question. Who, he asked, gave Trump’s tariff announcement the biggest shout out? When I confessed I did not know, he told me: Democratic Senate Leader Chuck Schumer.

Considering all these factors, despite the conciliatory words from President Xi in his speech at the Boao conference last week, recurring hopes for a quick resolution to the tariff war and return to business as usual seem to me unfounded. Indeed, my bet is that what we have known as “business as usual” in relations with China is now forever in our rearview mirror. We have moved into new, uncharted terrain in which the dangers are greater than the opportunities.

As we think about how much worse it could become, hard as it is to believe, prudence requires that we consider whether these two nations could even stumble from a trade war to a real war with bombs and bullets. To stimulate our imaginations, we should again consult Thucydides. Xi and Trump almost seem to be competing to see who can best exemplify the role of the leader of the rising and ruling powers. Xi’s rendition of the rising power’s confidence, growing ambitions, increasing assertiveness, and arrogance in his “Made in China 2025” plans to dominate ten major sectors (including advanced manufacturing, the Internet Plus, driverless cars, and AI) would make the Athenian leader Pericles blush. The alarm, anxiety, and even angst of a Washington that is awakening to discover a Chinese juggernaut that is not only rising, but has risen to rival—and in many arenas surpass—the United States echoes the “fear that this instilled in Sparta” of which Thucydides wrote.

In this dangerous dynamic, misperceptions are magnified, miscalculations multiplied, and risks of escalation amplified. Recent American history provides instructive clues about two slippery paths from the emerging trade conflict with China to a real shooting war: Pearl Harbor and the Korean War. In the first, to punish Japan for its military aggression against its neighbors in the 1930s, the United States initially imposed an embargo on exports of high-grade scrap iron and aviation fuel to Japan. When these failed to stop its aggression, Washington ratcheted up its sanctions to include essential raw materials such as iron, brass, and copper—and, finally, oil. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s August 1941 embargo proved to be the proverbial straw. Eighty percent of Japan’s oil came from the United States. Japan depended on that imported oil to fuel its military operations and keep its manufacturing plants humming. Without understanding what it had done, the Roosevelt administration’s actions thus forced Japan to choose between capitulation and conflict. Viewing this as a mortal threat, Japan’s ambassador told Washington on December 2, 1941, “The Japanese people believe . . . that they are being placed under severe pressure by the United States to yield to the American position; and that it is preferable to fight rather than to yield to pressure.” In desperation, Japanese leaders approved a plan to deliver a preemptive “knockout blow” at Pearl Harbor. The designer of the attacks, Admiral Yamamoto, told his government, “In the first six months to a year of war against the United States and England I will run wild, and I will show you an uninterrupted succession of victories.” But he also warned them: “Should the war be prolonged for two or three years, I have no confidence in our ultimate victory.”