How a Trust Deficit Holds China Back

Having finally acknowledged and engaged in strategic competition with the People’s Republic of China, we must effectively employ all the advantages of our liberal democratic system—especially rapid, distributed, and effective decision-making. This can only be accomplished by employing trust to delegate authority.

In a speech last week, President Joe Biden noted that Xi Jinping “firmly believes that China, before the year [20]30, ‘35, is going to own America because autocracies can make quick decisions.” (Emphasis added.) But can they? And are democracies invariably “slow?”

One way to answer is to look at the dynamics of decision-making, especially at the highest level of national governance.

In an enterprise as large as the United States or China, effective decision-making requires trust. Trust enables delegation of authority and distribution of decision-making, which keeps governments operating at the speed of relevance. An important difference between decision-making in democratic versus authoritarian governments boils down to the element of trust.

Consider the importance of trust in national security decision-making. The U.S. Constitution entrusts cabinet secretaries with the authorities required to execute their part of the national security strategy. Where agency authorities intersect, the National Security Council (NSC) has a convening role to ensure multiple interests are coordinated.

In the U.S. system, trust between the president and the cabinet allows the chief executive to delegate authority, knowing that his cabinet will take actions supportive of his agenda, and will do so in creative and innovative ways. Trust leverages input from a broad swath of perspectives and experiences, ensuring timely, creative, and elegant solutions.

The NSC system fails when cabinet members abdicate their authorities to the NSC, creating the sort of gridlock we see in a system devoid of trust—Chinese authoritarianism.

Contrary to common characterizations—including those apparently promoted by General Secretary Xi Jinping himself as repeated by the president—the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has not responded quickly or effectively when challenged over the last four years.

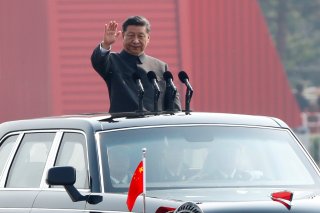

A big part of the reason is there is a paralyzing lack of trust within the CCP system. This is evidenced by Xi taking unto himself the final decision authority of nearly every activity in the Chinese government—evidenced by his personal leadership of twenty-one Leading Small Groups.

Although Mao Zedong ruled similarly, Deng Xiaoping’s (1904-1997) greatest innovation after the madness of the Mao era was to empower the bureaucracy—particularly those responsible for economic development—to make and execute policy on their own authority. In other words, to trust them.

Deng’s changes energized the ossified Communist system and leveraged the wisdom and talents of many, enabled by an emphasis on meritocratic leadership. Bureaucrats were sent to the United States (and elsewhere) to study in Western schools, where they learned the importance of free and open thinking.

This practical approach was most popularly captured in Deng’s dictum “it matters not if a cat is black or white; if it catches mice, it’s a good cat.” The benefits of this approach are obvious to all; consider the breathtaking pace of China’s development between 1980-2008.

The advent of Xi Jinping brought a return to single-point-of-failure consolidated decision-making in response to the geometric growth of corruption as China grew richer (corruption is a manifestation of a loss of trust). However, that consolidation of authority has now exceeded all expectations. One manifestation was the reduction of the Politburo Standing Committee, whittled down from nine to seven members, and then packed with yes-men.

At the same time, Xi Jinping destroyed trust in the leadership system itself by abandoning the traditional ten-year leadership term, in an unfortunate return to the Mao years. Today, no one dares act on their own authority and risk getting sideways with the Great Helmsman/the Party’s Core/the People’s Leader (pick an honorific). If they do, they risk sharing the fate of former State Security chief Zhou Yongkang, accused of non-specific corruption and then “disappeared” from public life. Numerous People’s Liberation Army (PLA) generals have shared Zhou’s fate. In Xi’s China, the system is shaped by fear, not trust.

Although bad for the Chinese people, this consolidation of executive authority under one supreme leader benefits the United States. During my time in government, the Chinese government was unable to respond in a timely or meaningful way to an energized, distributed Washington bureaucracy empowered by trust.

In the newly acknowledged strategic competition, we worked with the NSC to accelerate decision-making and execution, putting Beijing’s authoritarians on their back foot. As expected, the CCP’s single-point-of-failure system (with Xi Jinping as the core) locked up, making Beijing reactive and ineffective while the administration, supported by Congress, reasserted U.S. leadership vis-à-vis China.

The reinvigorated Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, a complex, multifaceted, and adaptive accomplishment that required not only trust within the U.S. system but with and within like-minded democratic partners, stands as a testament to this. Xi’s CCP is incapable of accomplishing anything similar.

Having finally acknowledged and engaged in strategic competition with the People’s Republic of China, we must effectively employ all the advantages of our liberal democratic system—especially rapid, distributed, and effective decision-making. This can only be accomplished by employing trust to delegate authority.

Excessive bureaucratic coordination, in the hope of minimizing political risk, is the antithesis of all this. Although decisions and actions bring risk, greater risks come with inaction. Without delegation and distribution of authority based on trust, we risk returning to an era of ceding the initiative to Beijing, endlessly shooting behind the target.

Retired Brigadier General and former Assistant Secretary David Stilwell served in both the Obama and Trump administrations.

Image: Reuters.