Iran’s House of Cards

The Islamic Republic’s succession games are just getting started.

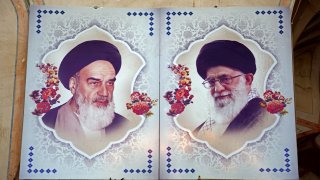

Masoud Pezeshkian’s election to Iran’s presidency remains a sideshow to the true contest for power in the Islamic Republic. Who will succeed to the leadership of the regime upon the death of eighty-five-year-old Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who has ruled Iran with an iron fist for the past thirty-five years? Until his death in a helicopter crash, Ebrahim Raisi was a favorite. He had the right credentials, serving not only in the presidency but also within the judiciary and managing a major religious shrine.

Raisi’s death leaves Mojtaba Khamenei, the fifty-five-year-old son of the current supreme leader, well-positioned to succeed his father. On paper, Mojtaba is just a teacher at a seminary school, even if, in actuality, he is the de facto manager of his father’s office, giving him a nuanced understanding of the leadership’s inner workings. He also enjoys close ties to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and the broader security apparatus.

The support from the regime’s security establishment could be crucial. Given the high stakes, Mojtaba will face challenges. Within the Islamic Republic, the supreme leader is the highest authority. He oversees the armed forces and can overturn almost any legislative or executive policy. He controls much of the country’s wealth and distributes resources, power, and status among his allies. Consequently, a new leader can expel his predecessors’ top officials from the inner circle or strip them of their status. As a new inner circle emerges, those close to the former leader can even be charged with capital offenses.

The past is prologue. The Islamic Republic has experienced only one succession event: Khamenei’s rise following the death of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989. At the time, Khomeini’s son Ahmad played a crucial role. Ahmad, working with Khamenei and then-parliamentary speaker Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, helped depose Khomeini’s designated successor, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri. Khamenei and Rafsanjani subsequently betrayed Ahmad. While Khamenei became supreme leader and Rafsanjani president, Ahmad was left powerless. He died six years later at age forty-nine under suspicious circumstances. The lesson Mojtaba draws is that his life depends on his ability to consolidate power.

Mojtaba theoretically faces competition from multiple camps, all of whom will argue that hereditary succession, despite the importance of hereditary leadership in early Shia history, will undermine an important tenet of a system that made ending hereditary monarchy a source of its own legitimacy. Many senior ayatollahs check all the boxes to aspire to leadership and mirror Khamenei’s uncompromising views but are likely too old. Ahmad Jannati, for example, a regime luminary who currently chairs the Guardian Council that vets candidates and laws, is ninety-seven years old.

The “reformists,” attractive to many in the West because of their softer rhetoric, could also elevate a challenger. Khamenei, however, has managed to marginalize the camp’s most notable figures, such as former Presidents Mohammad Khatami and Hassan Rouhani, or Khomeini’s grandson Hassan.

In theory, Sadeq Larijani, a conservative former chief justice who currently chairs the Expediency Discernment Council, could rise to the challenge. However, seeing the threat, both Khamenei and Raisi moved to marginalize him.

This leaves less notable hardline figures such as Ahmad Khatami (no relation to the former president), Mohsen Ghomi, or Alireza Arafi. Khatami and Arafi lack meaningful executive experience. Ghomi, a young cleric, is an exception. As Khamenei’s advisor for international affairs, Ghomi previously supervised the supreme leader’s links to universities. Ghomi, however, is junior and effectively subordinate to Mojtaba.

Khamenei has yet to give any indication of his true wishes regarding his son’s succession. While some reports suggest Khamenei defends his son in private, he has not made any public statement about Mojtaba. Other accounts indicate he is opposed to hereditary succession. With no designated heir, the fight over succession will continue and, as Khamenei ages, will accelerate. Mojtaba may be the front-runner, but his power may plummet the moment Khamenei is gone.

The fight will be bloody, and Mojtaba’s succession is not yet certain. Still, for Iranians who want freedom and regional leaders who seek peace and an end to Islamic Republic-sponsored terror, any successor will likely disappoint.

Janatan Sayeh is a research analyst at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) focused on Iranian domestic affairs and the Islamic Republic’s regional malign influence. Follow him on X @JanatanSayeh.

Dr. Saeed Ghasseminejad is a senior advisor for Iran and financial economics at FDD, specializing in Iran’s economy and financial markets, sanctions, and illicit finance. Follow him on LinkedIn and X @SGhasseminejad.

Image: Attila Jandi / Shutterstock.com.