ISIS’ Desire to Erase Sykes-Picot Is Rooted in Fiction, Not History

"Western governments should not be too quick to accept ISIS’ wish to write off existing borders."

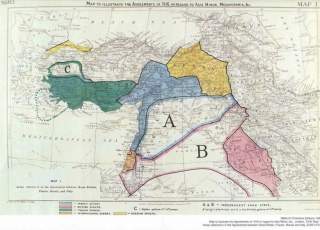

The rise of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) raises the possibility that the days are numbered for the map of the Middle East as we know it. ISIS has stated that it wishes to erase the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 that delineated state borders in most of the modern Middle East, and it has even changed its name to the Islamic State (IS), removing the reference to Iraq and Syria as separate countries. According to the Washington Post, the United Nations, U.S. Department of State, Associated Press and President Obama refer to the organization as ISIL, which stands for the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. The term “Levant,” which includes the Mediterranean coast and Jordan, is a more direct translation of the Arabic “al-sham,” and warns of the group’s regional aspirations. However, ISIS’ shift to calling itself “IS” expresses a desire to eradicate the states of the Middle East that even the archaic word “Levant” does not convey.

ISIS is not alone in viewing Sykes-Picot as obsolete; some Western commentators view the Sykes-Picot map as a colonial contrivance that has passed its expiration date. British diplomat Paddy Ashdown wrote in The Guardian last month that it is “better, surely, to face up to the realities of the post–Sykes-Picot Middle East.” However, both Middle Eastern history and cartography existed long before 1916, and Syria and Iraq were distinct entities, not only in the pre-WWI Ottoman era, but also before and after the rise of Islam in the seventh century, even though the exact borders were not always clear or in their present-day form. Therefore, Western governments should not be too quick to accept ISIS’ wish to write off existing borders.

Modern-day Syria and Iraq both have antecedents in the pre-Islamic world. In the sixth century, the Arab tribal kingdom of the Ghassanids was located in much of the same area that is now Syria, while the Lakhmid kingdom was based in Iraq. These tribes fought each other as proxies for the two great world powers at the time: the Byzantines and Sassanians. With the establishment of Islam as a political and religious community in seventh-century Arabia, Muhammad briefly managed to unite disparate Arab tribes under the banner of Islam. However, many of the old divisions reappeared after Muhammad’s death, when Islam continued its expansion out of the Arabian peninsula.

The reality is that Syria and Iraq have often been ruled by distinct regimes, despite the supposed unification of the Islamic world under the caliphs. When the Umayyad caliphate ruled in Damascus, Iraq was a hotbed of dissent. And when the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads in 750, they deliberately moved the capital out of Damascus and into the newly-built Baghdad. Thereafter, the two territories were often ruled separately, including when Syria was dominated by Crusader kingdoms and Iraq by the Seljuqs. Although the Ottomans restored a measure of unity, the territories remained distinct administrative units within the empire. ISIS envisions a return to a time before the creation of modern nation-states, imagining the Middle East as a borderless desert that caliphs ruled in the name of Islam. However, it is ISIS’ vision of past unity that is falsely constructed.

In proclaiming Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as the new caliph ruling over a united Syria and Iraq, ISIS is not invoking any accurate conception of Islamic rule in the seventh century or thereafter. Its dream of a caliphate that erases the border between Syria and Iraq ignores not only the history of the region before the twentieth century, but also that—sectarian divisions notwithstanding—the two countries have developed independently since the early twentieth century. ISIS’ vision is, ultimately, deeply ahistorical; rather, ISIS is using the past as a fig leaf to justify an opportunistic military campaign that capitalizes on the lawlessness wrought by Syria’s civil war and on the weakness of Iraq’s security forces. Western leaders should therefore think twice before accepting the argument that redrawing the lines on the map of the Middle East will necessarily be more legitimate than the status quo.

U.S. foreign-policy circles are justifiably frustrated with the seemingly intractable nature of Syria’s civil war and Iraq’s political and security failures, and it may be tempting to throw out a border that appears to have been drawn on a map to suit French and British colonial interests. But although the border between Syria and Iraq is a thin, vulnerable line—bulldozed in recent months by ISIS fighters—the historical split between Iraq and Syria is not so easily erased. Any attempt to impose new borders or to redraw the maps along, say, sectarian lines would also be an imposition of Western power and would most likely open an entirely new Pandora’s box. It is up to Syrians and Iraqis—not Western governments or ISIS and its foreign fighters—to determine the future of their countries.

Jennifer Thea Gordon was a US Government analyst on Middle Eastern issues and has a PhD in Islamic history from Harvard University.

Image: Flickr/prince_volin/CC by-sa 2.0