Making History Great Again

Simon Sebag Montefiore’s book, Titans of History: The Giants Who Made Our World, offers a jaunty tour of past historical greats.

Simon Sebag Montefiore, Titans of History: The Giants Who Made Our World (New York: Vintage Books, 2018), 640 pp., $20.00.

SIMON SEBAG Montefiore is one of those rare writers who knows how to put the story back into history. In his earlier books, he combined solid research with a knack for turning long-dead figures into vivid characters. In Catherine the Great and Potemkin, a doorstop of a book, he explored the tempestuous romantic and professional relationship between the Russian empress and her swashbuckling lover, bringing to life a period that has rarely received its due. In The Court of the Red Tsar, he illuminated Joseph Stalin’s tyrannical rule by tracing the intricate and incestuous bonds among the Bolshevik elite. In Jerusalem: The Biography, he managed to transform an entire city into an eccentric persona.

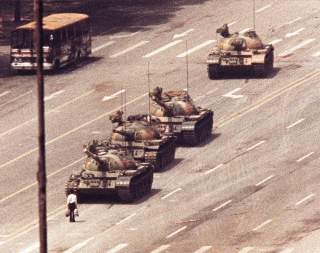

His new book, Titans of History, may be his guiltiest pleasure yet. It brings together dozens of mini-biographies of the most interesting people of the past three thousand years—starting with Rameses the Great (1302–1213 BC) and winding up with Osama bin Laden (1957–2011) and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the founder of isis. (I’m taking a minor liberty here. Actually, the book ends with the semi-mythical figure of Tank Man, the anonymous citizen who courageously defied the Chinese military during the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989—but since we don’t really know anything for sure about his identity, Montefiore uses him as a kind of cipher of the human desire for freedom from tyranny. Plus, he’s out of sequence.)

THIS WORK departs significantly from Montefiore’s previous efforts in some respects. For one thing, it’s a collective effort: Montefiore credits four co-authors with the research for his globe-spanning project. The style of these bite-sized biographies, however, is unmistakably Montefiore’s—he was clearly responsible for buffing each part to his customary high shine. Throughout, Montefiore exhibits a keen eye for the telling detail and juicy anecdote.

Here he is on Aristotle: “This wealthy dandy, who sported jewelry and a fashionable haircut, championed the mind above all else.” Casanova “represented a sparkling conflation of two eighteenth-century social types – the society fraud and the man of letters.” In the chapter about the Byzantine Emperor Justinian and his formidable wife Theodora, Montefiore makes this observation about the famous “Secret History” of their courtier Procopius: “One has to read it as one might a twenty-first-century tabloid newspaper – half of it may be a toxic mix of satire and tittle-tattle – but some of it must have been true.” None of which stops Montefiore from quoting it at length, as well he should.

Go back far enough in history, of course, and the tittle-tattle is sometimes just about all we have to go on: the tendentious accounts written by the victors (or the disgruntled victims). Montefiore writes with great nonchalance about Jesus, for example, even though most of what we know about him comes from four mutually contradictory texts that were written down decades after he died. (Some scholars still aren’t even sure whether he existed.)

And Montefiore’s pocket biography of Judas the Maccabee includes the following line: “Even though the oil for the Temple lamp had run out, the lamp remained alight for eight days, a miracle that inspired the joyful Hanukkah Festival of Lights, in which Jews still celebrate religious freedom from tyranny.” I don’t think we’re supposed to take this statement at face value—but who cares, really? Never let the truth get in the way of a good story, as the guy once said.

Montefiore cannot be accused of false advertising. In the introduction he notes: “This list can never be either complete or quite satisfactory... There may be names you think are missing and others whose very inclusion you question: that is the fun and frustration of lists.”

He’s exactly right about that. We may not have entirely been conscious of the fact until the Internet came along, but now there can be no doubt: lists are fun. I don’t think Montefiore set out to write a book-sized listicle, but he has certainly embraced the spirit of the genre. Every now and then, as I made my way through these bite-sized character portraits, I couldn’t help pondering how they could be transformed into clickbait: Remember Lucrezia Borgia? You won’t believe what she looks like now. I look forward to reading Buzzfeed’s review of the book.

IT IS hard to believe some of the people Montefiore left out of his conspectus of the great and mighty throughout the centuries. He devotes only a few lines to the Apostle Paul, the man who arguably transformed monotheism into a global phenomenon—and they’re folded, almost as an afterthought, into the section on Jesus. He gives a nice gloss on Barbarossa, but never mentions Martin Luther. His portrait of Lenin is admirably punchy, but there’s no chapter on Karl Marx. And he writes a glowing passage about Elvis Presley while completely neglecting Martin Luther King, Jr.

Does Montefiore evince a certain aversion to ideology, indeed, even to ideas as such? His sketch of Aristotle dwells lovingly on the philosopher’s personal quirks, but it barely touches upon his actual thought—which is, after all, the whole reason why we remember him today. Surely ideas are one of the most powerful ingredients in human history, often shaping world-historical figures just as much as they shape it.

But intellectual history is a tough sell—much less so than the stuff that really piques Montefiore’s interest. Here’s how he lays out the case in his introduction to the book:

Greatness needs courage (above all) and willpower, charisma, intelligence and creativity, but it also demands characteristics that we often associate with the least admirable people: reckless risk-taking, brutal determination, sexual thrill-seeking, brazen showmanship, obsession close to fixation and something approaching insanity. In other words, the gap between evil and goodness is a thin one: the qualities required for greatness and wickedness, for heroism and monstrosity, for brilliant, decent philanthropy and brutal dystopian murderousness are not too far distant from each other. The Norwegians alone have a word for this: stormannsgalskap – the madness of great men.

He’s right, of course. The ferocious ambition that drives certain people to the top often includes a healthy dose of sheer psychopathy; genius frequently exists in direct proximity to the demoniac. (Odd that this book doesn’t include at least a mention of Goethe and his Faust.) Dr. Johnson, whom Montefiore hails for his erudition and versatility, oscillated between crippling depressions and manic productivity: “I hate a fellow whom pride or cowardice or laziness drives into a corner, and who does nothing when he is there but sit and growl,” he said. “Let him come out as I do, and bark.” If anything, Johnson was a gladiator battling in his personal colosseum, smiting his foes down, one after the other.

SOMETIMES MONTEFIORE’S fondness for the lurid goes a bit far. His chapter on Vlad the Impaler—a titan of history? Really?—lingers over the man’s vast atrocities with a detail rarely seen. As a glass-half-empty kind of person myself, I’m fully willing to acknowledge that a good ninety-five percent or so of history can be measured by body counts: the casualties of war, tyranny and religious passions. (Aside from which, readers just don’t tend to click on the good guys.) Plus, you didn’t get ahead in medieval times by demonstrating your devotion to etiquette. Montefiore describes the Emperor Basil II as “one of the most powerful and effective rulers of the Byzantine Empire, the ultimate hero-monster.”

The author’s repeated use of the phrase “great man” evokes Thomas Carlyle and his Romantic notions of the towering individual—but it could also be that Montefiore is just a bit of a lad. Though he works in a Cleopatra here, a Margaret Thatcher there (not to mention Sarah Bernhardt), one can’t help feeling that he would much rather write about the lads—the badder, the better. Alexander Pushkin is “a passionate and promiscuous lover of women.” Benjamin Disraeli’s “sex life was shocking.” “Ibn Saud had always prided himself on his prowess as a fighter and a lover.” Samuel Pepys’ diaries “seethe not just with glimpses of the gorgeous underwear of Charles II’s latest mistresses but of Pepys’ sexual adventures too.”

What’s more, his verdicts are seldom less than sweeping. Frederick the Great is approvingly described as the German leader who built up the Hohenzollern dynasty: “this apparent milksop astonished Europe’s crowned heads by becoming the most formidable ruler of the age.” By contrast, Kaiser Wilhelm is summarily dismissed as something of a nutjob:

the last emperor of Germany—known to the British simply as the kaiser—was an inconsistent, bombastic, tactless, preposterous, perhaps even mentally deranged, absolutist monarch who managed to gain control of German military and foreign policy yet who ultimately proved unable to govern or sustain his own power.

He forgot to throw in conceited and vain about the monarch who was indelibly parodied in Thomas Mann’s splendid 1909 novel His Royal Highness, which was turned into a West Germany comedy movie in 1953. Did Wilhelm prefigure the rise of Hitler? Montefiore rightly calls the latter the embodiment of evil who by the end of World War II “spent his time ordering nonexistent armies to launch nonexistent offensives, denouncing his potential successors Goering and Himmler as traitors, and holding twee tea parties with his devoted female secretaries.”