McMaster's Experiences with Strategic Failures Will Lead Him to Success

Time for America to ditch its whack-a-mole counterterrorism strategy.

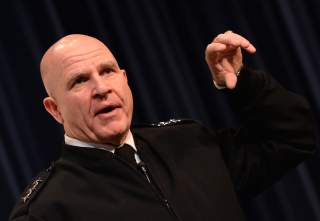

Of all of the candidates that President Donald Trump interviewed to be his next national security advisor, Lt. Gen. H. R. McMaster was by far the most unconventional. A veteran of multiple U.S. wars, commander during numerous deployments and acclaimed by his peers as a strategist who prides himself on innovative thinking, McMaster will undoubtedly meet his match in his new position.

A national security advisor must have the complete confidence of the president and the bureaucratic fortitude to play the honest broker between the national-security community’s numerous departments and agencies, namely the Department of Defense and Department of State. And as Condoleezza Rice quickly experienced firsthand during President George W. Bush’s first term, the national security advisor is only as good as his or her ability to manage the large egos who serve on the president’s cabinet.

The important responsibilities of a national security advisor are almost endless: knowing when to speak truth to power; when to challenge the more hawkish elements of the Washington foreign-policy community; how to provide the full range of options to the president’s desk during principals committee meetings; and when to exhibit the qualities of the hardheaded quarterback to ensure the trains run on time and all of the departments effectively implement the president’s national policies.

None of this, however, will matter at all if the United States continues to avoid establishing grand strategy that has largely been missing from the discussion since the advent of the war on terrorism. To put it in another way, you can be the most talented CEO in the world and still watch your company go bankrupt if you aren’t able to find a strategy suitable to the times.

Ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1992, the United States has primarily approached the world through the prism of being the lone superpower—the one nation that calls the shots, advocates for universal liberal values, and guarantees that the international system that the United States established after World War II continues to define how the world operates.

With no peer competitor on the horizon and with an economy and military budget far larger than any other country could muster, the United States suddenly entered a new era that afforded it with a unique and unimaginable position of facing virtually no national-security threats and the most powerful military known to mankind.

The United States, in effect, got greedy. The absence of a major adversary in the international system meant that missions that were previously secondary—democracy promotion, the extension of trade ties, the expansion of globalization—were now driving foreign-policy decisionmaking. Rather than leading by example and serving as a “shining city upon a hill,” as President Reagan put it, America deployed its military to solve the internal conflicts of nations and reshape entire regions by force.

Military, economic and diplomatic resources that were previously used to contain Soviet expansion in Europe, Asia and Latin America were now utilized to advance America’s military footprint, punish dictators like Saddam Hussein who were violating international law, intervening to stop other dictators from committing genocide and bankrolling opposition movements (like the Iraqi National Congress) to replace tin-pot authoritarians with pliant, U.S.-friendly governments.

Regime change became a bipartisan way to snuff out perceived challenges to the liberal international order. After three regime change operations in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, a reactive whack-a-mole counterterrorism strategy was created that continues to this day. A war in Afghanistan that was launched to kill or capture those responsible for the most horrific attack on America has transformed into an impossible, unsuccessful nation-building campaign that has lasted twice as long (and counting) as the Vietnam War. This strategic failure is, unfortunately, not the exception.

The United States finds itself in the year 2017 without much of a grand strategy and very little sense of where its priorities lie.

As Professor Barry Posen told the Atlantic in 2014, Washington, DC has too often lost the forest for the trees—”We don’t have to transform the world, spread democracy, expand NATO, or any of these other things,” Posen said. “But there are a few things that we need to pay attention to. We need what I would call moderate, pragmatic strategies to work on those problems.”

This is perhaps the most critical task that President Trump will expect Lt. Gen. McMaster to carry out. What are the real crises and challenges in the world today that, if not dealt with or mitigated in time, could increasingly impact America’s strategic posture for the worse, limit the country’s access to key shipping and trading routes, force its allies to consider bandwagoning with rivals and restrict the nation’s flexibility? Which problems, in contrast, are best left to regional governments to deal with?

The time when the United States could get away with doing everything and anything almost everywhere without having to worry about the consequences to America’s power, prestige, financial well being and reputation are over.

In a December 2015 article for the American Conservative, Professor Andrew Bacevich of Boston University wrote, “For a rich and powerful nation to conclude that it has no choice but to engage in quasi-permanent armed conflict in the far reaches of the planet represents the height of folly.” Bacevich understands that kind of folly well; as a first lieutenant in Vietnam, he saw through firsthand experience how a war based on faulty assumptions and a simplistic war strategy driven by fear and hubris could hurt an entire nation, even one as powerful as the United States.

When the Vietnam War finally ended (for the United States at least), more than fifty-eight thousand Americans were dead, one million Vietnamese had perished and the U.S. Army was stuck in a morass from which it wouldn’t fully recover for at least a decade.

Ironically enough, H. R. McMaster is an expert on the failures of America’s involvement in Vietnam. Writing in his widely read book Dereliction of Duty, McMaster showed the extent to which the unity of an entire country can suffer when politicians and commanders in Washington make bad decisions.

Now that he’s the head of the National Security Council, Lt. Gen. McMaster will have the access, authority, influence and responsibility to make sure that the United States learns from its mistakes and develops and follows a grand strategy that is as strong and unyielding as it is pragmatic and realistic in the protection of U.S. national-security interests.

Daniel DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities.

Image: H. R. McMaster speaks at the U.S. Naval War College. DVIDSHUB/Public domain